Lee Christofis reviews 'The Sleeping Beauty' (Australian Ballet)

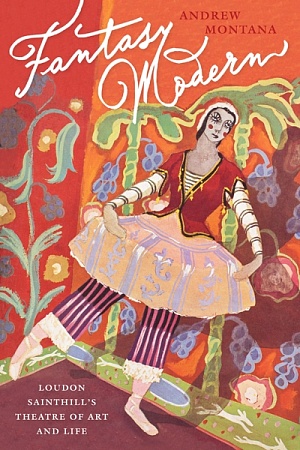

When Sergei Diaghilev staged The Sleeping Princess at the Alhambra Theatre, London, in 1921, he hoped to prove that classical ballet could be as popular as the outrageously glamorous West End hit, Chu Chin Chow, which ran for five years. Diaghilev invited the brilliant colourist Leon Bakst to design sets and costumes equal to those of the original 1890 St Petersburg production, choreographed by Marius Petipa to a new, majestic Tchaikovsky score, in décors by no fewer than six artists.

Bakst far exceeded his brief and the London crowds, used to Diaghilev’s exotic one-act Ballets Russes works, were stunned into submission under the weight, just as the Russians were in 1890. The endless dancing and the lack of dramatic action also baffled them; only the murderous fairy Carabosse and her swarming rats appeared to ruffle the serene life of the Beauty, Princess Aurora. Diaghilev’s Sleeping Princess ran for three months, unheard of until Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake and its half-naked, male birds landed on London twenty years ago. But Diaghilev’s TheSleeping Princess was a financial disaster; the production bankrupted him and burnt his backers.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.