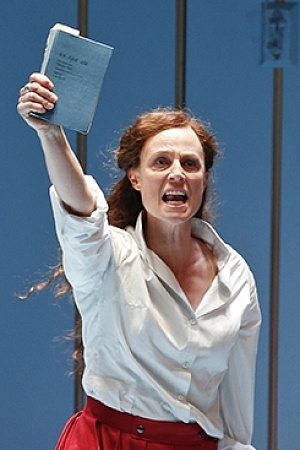

Faust and Verdi's Requiem (State Opera of South Australia)

Good and evil, damnation and salvation, love and death, virtue and folly: State Opera of South Australia’s pairing of Gounod’s five-act grand opera Faust (![]() ) with Verdi’s momentous opera cum oratorio Requiem

) with Verdi’s momentous opera cum oratorio Requiem

(![]() ) epically traverses the profoundest bays of the human condition. Together, they round out a season inaugurated by Mozart’s Don Giovanni, another staple of the repertoire that has at its heart the promise of divine justice.

) epically traverses the profoundest bays of the human condition. Together, they round out a season inaugurated by Mozart’s Don Giovanni, another staple of the repertoire that has at its heart the promise of divine justice.

Their first performances a mere fifteen years apart – Faust in Paris in 1859, Requiem in Milan in 1874 – the two works are also connected by their inauspicious beginnings. Faust was rejected by the Paris Opéra and kept off stage for a year while Adolphe d’Ennery’s drama, similarly based on Goethe’s tragedy, was playing in the same city. The Requiem, with its unusual hybrid form, its call for female singers, and the perceived rift between its religious themes and dramatic musical expression, did not find immediate favour in Italy. It was not until the 1930s that the work entered the standard choral repertoire. Now, like Faust, it is a fixture, having become a sort of musical shorthand for titanic struggle – floating over New York radios in the wake of September 11, and newly theatricalised by Oper Köln, with nods to Fukushima and Aids.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.