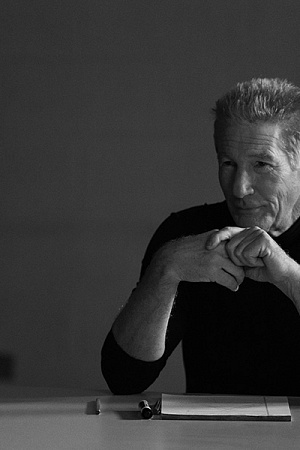

Joseph L. Mankiewicz: The essential iconoclast

Joseph L. Mankiewicz (1909–93), a screenwriter, producer, and director of films in Hollywood for over forty years, is the latest to receive repertory profile treatment at the 52nd New York Film Festival. Entire-career retrospectives are always interesting events; they are at once a celebration of auteurism and a complication of it. Nobody’s career is flawless, and a retrospective like this inevitably puts its weak spots out in the open. Pauline Kael once wrote that it is an insult to someone’s career to praise their bad work along with their good; it belied an incapacity to judge either. Retrospectives are at risk of this, yet viewing all work at once allows for an appreciation of elements that might be dismissed at individual viewings.

Mankiewicz had received Academy Award nominations for screenwriting and producing before directing his début at Twentieth Century Fox. Originally slated to be directed by Ernst Lubitsch, the latter encouraged Mankiewicz to direct his own script of Dragonwyck (1946). This first film is excellent, a rich gothic melodrama with intricate close-ups and vivid backgrounds, a lasting feature of Mankiewicz’s work. It is unsurprising that All About Eve (1950) and A Letter To Three Wives (1949), for which he received Best Director Oscars, were the best attended of the season. Mankiewicz regarded these two films as his legacy. But he brought the same melodramatic intensity even to his lesser-known works.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.