Nuremberg

There is a classic sketch from That Mitchell and Webb Look, a BBC series from the mid-2000s, in which its two lead comedians stand in a World War II dugout, dressed as Nazi SS officers. After properly examining the skull decorations on their uniforms, one of them has a revelation: ‘Wait … are we the baddies?’ The joke here, of course, is that true evil never recognises itself as evil, regardless of how many skulls adorn one’s uniform or how many unthinkable atrocities one commits. The worst people in history have all passionately believed their own causes to be righteous, thanks mostly to inhuman feats of self-delusion and occasional instances of good old-fashioned insanity.

In James Vanderbilt’s Nuremberg, it is the task of American military psychiatrist Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek) to separate such delusion from madness in the surviving vestiges of the Nazi high command, following their defeat at the hands of the Allies in 1945. Hitler is dead; Goebbels is dead. Along with twenty-or-so other ranking officers, this leaves Hermann Göring (Russell Crowe) – Supreme Commander of the Luftwaffe, President of the Reichstag, and Hitler’s immediate successor – as the most senior Nazi answerable for the Third Reich’s crimes.

American Justice Robert H. Jackson (Michael Shannon) is preparing to hold a tribunal in Nuremberg, the first of its kind, which will battle-test the very feasibility of international law and see Hitler’s lackeys held accountable, then punished, on the world stage. Why bother with the pretence of justice for such barbaric, obviously guilty men? Jackson reasons that extrajudicial executions would make martyrs of them all. He wants a trial and a sentence so as to reduce them to common criminals, disgraced and then forgotten: ‘No songs, no statues.’

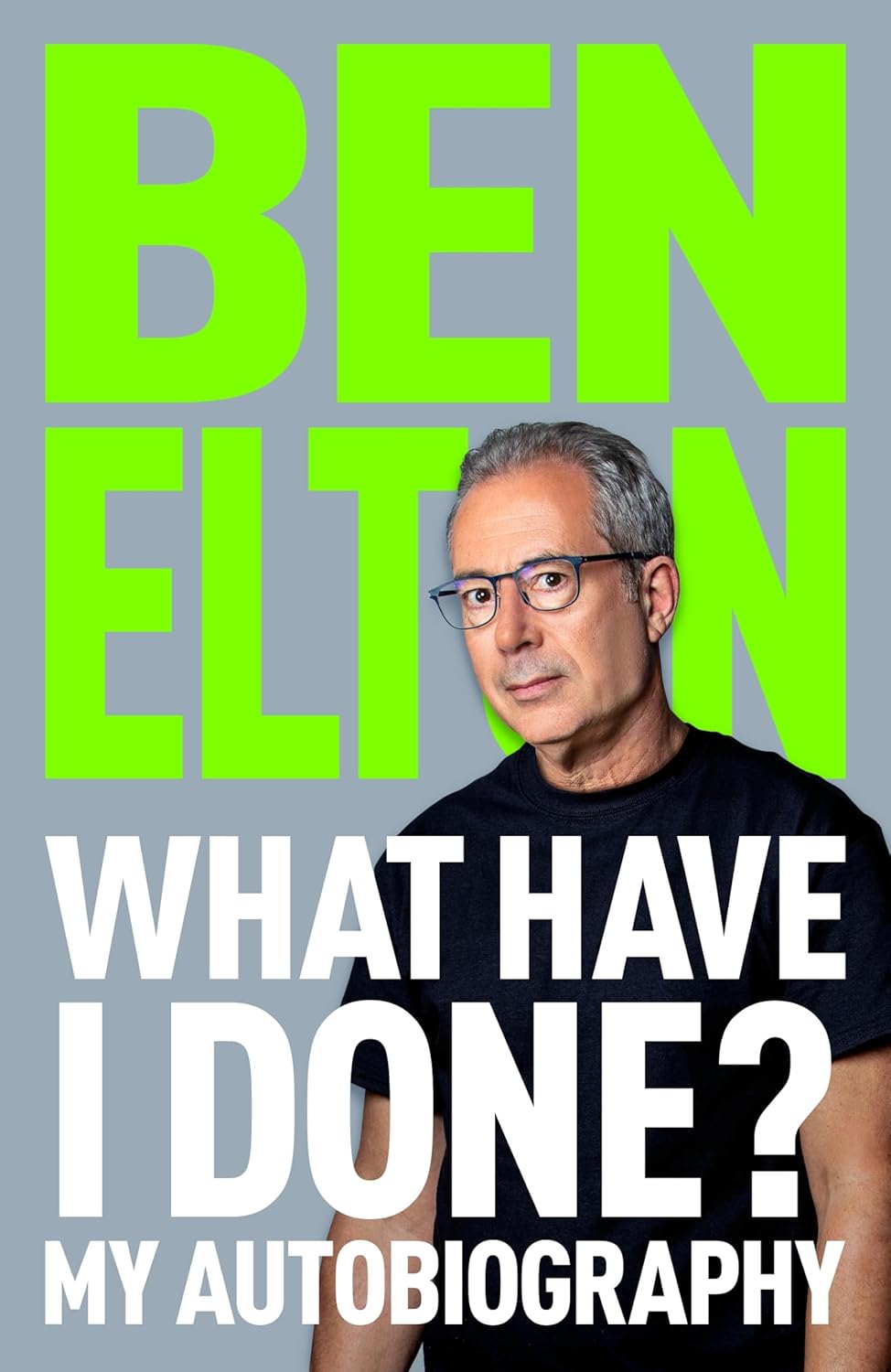

Rami Malek as Lt. Col. Douglas Kelley and Leo Woodall as Sgt. Howie Triest in Nuremberg (photograph by Scott Garfield, courtesy of Madman Entertainment)

Rami Malek as Lt. Col. Douglas Kelley and Leo Woodall as Sgt. Howie Triest in Nuremberg (photograph by Scott Garfield, courtesy of Madman Entertainment)

These trials were a historical flashpoint, broadcast around the globe. For the most part, the sleek yet perfunctory Nuremberg, based on Jack El-Hai’s non-fiction book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist (2013), attempts to frame this battle for the world’s eternal soul as a psychological joust between two men, Göring and Kelley. As Göring, Crowe oscillates between gregarious and menacing, using his physical heft and rumbling baritone to excellent effect. It is a performance deserving of a better sparring partner, of a finer Clarice Starling to his convincing Hannibal Lecter.

Many of the film’s problems lie with Malek as Kelley. We meet the ‘hotshot head shrink’ en route to Nuremberg, sporting a leather jacket, sunglasses, and a cool card trick he likes to use to seduce pretty girls on trains. The moment he learns he has been assigned to monitor Göring, he sees dollar signs; he imagines a bestselling book, one that might finally ‘psychologically define evil’. Naturally, his motivations change over time, but Malek overplays every second of his character’s transformation from opportunist to do-gooder to maligned truth-teller. What’s more, Vanderbilt’s script fails to convince us that Kelley’s work has any meaningful bearing on the outcome of the trial. It is impossible to tell whether he’s even any good at his job. After supposedly ‘thousands of hours’ spent one-on-one with Hitler’s right-hand man, Kelley comes away with about as much psychoanalytical insight as a BuzzFeed personality quiz. ‘Göring is a narcissist!’ Whoever would have guessed?

Elsewhere, Michael Shannon, John Slattery, and Richard E. Grant make much lighter work of the material, even as they speak in vague moral truisms and postmodern quips, occasionally exchanging biographical information from their characters’ Wikipedia pages. If only they’d been working from a script more akin to writer Abby Mann and director Stanley Kramer’s towering 1961 Judgment at Nuremberg, about an adjacent trial of Third Reich judges. In that film, the rigidity and ritualism of the courtroom sequences mask simmering, unspeakable wells of anger and sorrow on both sides.

While Judgment at Nuremberg depicts postwar history as living memory, painful and ever-present, Nuremberg reduces that history to ham-fisted fantasy. We listen to casualty statistics and witness CGI landscapes of decimated cities, but outside of a single, belaboured monologue from translator Howie Triest (Leo Woodall), none of the characters seem to have any real personal connection to the decade of immeasurable violence which directly preceded the events of the film. Douglas Kelley saunters in as though the war never happened; did he not have friends, family, comrades who died? Nuremberg wears its morals all-too heavily but elides the raw grief that gives such morals meaning. Perhaps there is a point being made here about the justice system’s ultimate inability to reckon with crimes of this magnitude, or to ever fully make up for such monumental loss. Even Justice Jackson understands that the hanging of twenty-odd Nazi officers will always be more symbolic than genuinely reparative.

It is telling that Nuremberg’s most affecting sequence doesn’t rely on Vanderbilt’s script at all, but on newsreel footage, played during the real-life trials themselves, of the Nazi extermination camps as they were liberated by the Allies: hundreds of emaciated bodies being bulldozed into unmarked graves. It is as sickening and soul-destroying to watch now as it must have been eighty years ago. Nuremberg does little to reframe that horror.

Nuremberg (Madman Entertainment) is now screening in cinemas across Australia.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.