Jay Kelly

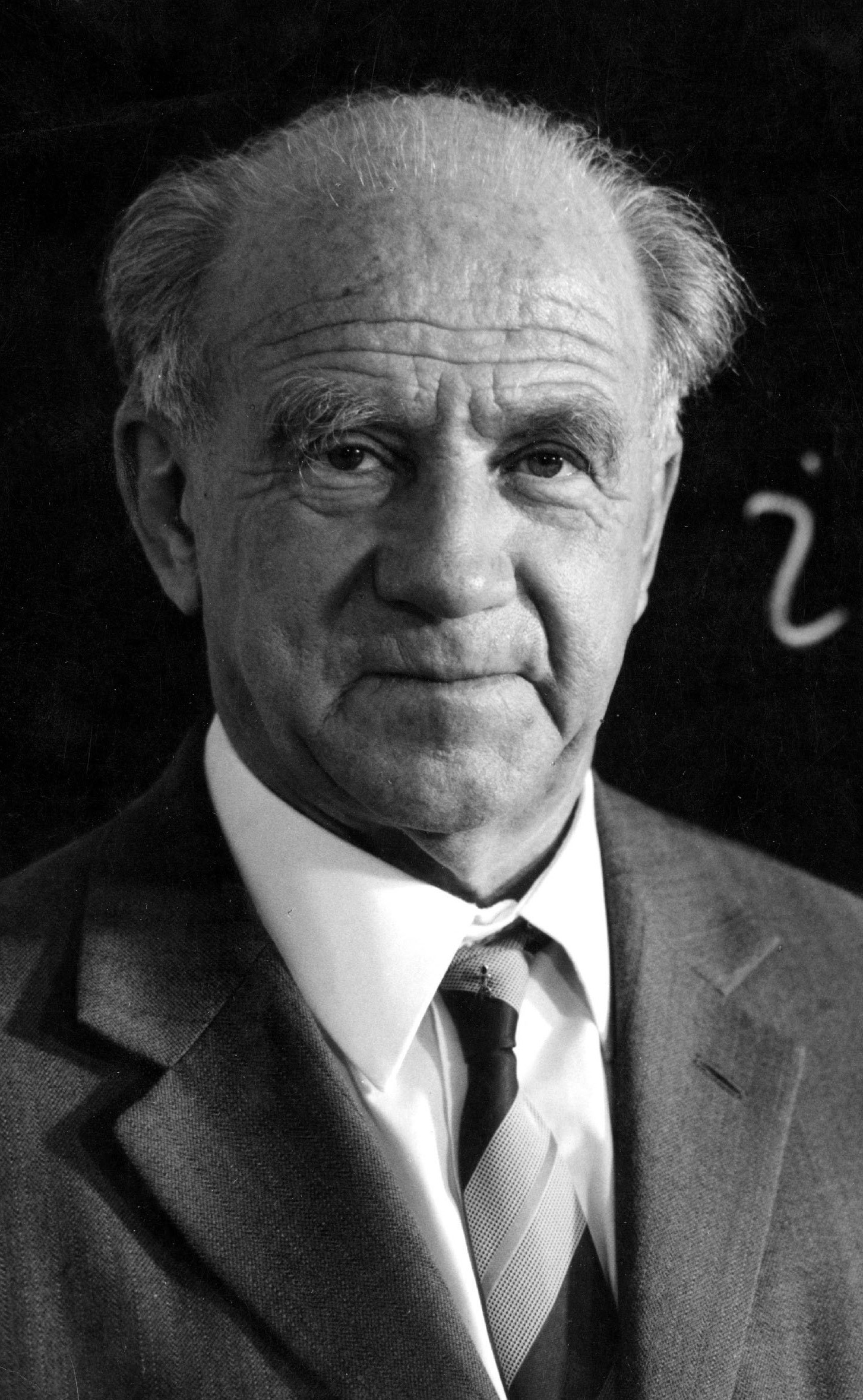

In the same year that Apple TV’s series The Studio (2025) took a scalpel to modern-day Hollywood – a Hollywood beset by pandemics, wildfires, union action, sparring tech barons, punitive politicians, and the creeping, existential threat of artificial intelligence – here comes Noah Baumbach’s Jay Kelly, along with its hero Jay Kelly (George Clooney). Both film and protagonist are handsome, genial, and seemingly apolitical – throwbacks to a different, simpler, no doubt more naïve time.

Ever since he sauntered onto our TV screens in ER, Clooney has been painted as the last in a long line of great leading men à la Brando and Cooper and Gable and Grant, even when his filmography has failed to live up to the same calibre. He has since embraced the role of a man out of time, a silver fox sipping Nespresso on his Lake Como balcony, while his own directorial efforts have been blinkered by a slavish devotion to mid-century American nostalgia.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.