My Sister Jill

Some of Australia’s most enduring plays have dealt with war and its legacy. Alan Seymour’s The One Day of the Year (1960), John Romeril’s The Floating World (1974), Dorothy Hewitt’s The Man from Muckinupin (1979), Kate Mulvaney’s The Seed (2008), and Tom Wright’s Black Diggers (2015) have, each in their own way, interrogated the baptisms of blood upon which much of our national mythology, our national identity, has been built. More often than not, that national mythology has been found wanting.

Patricia Cornelius’s My Sister Jill will rank high among these plays. For the first half of its ninety-minute running time, there is even a sense that it might emerge as one of Australia’s best plays about the debilitating consequences of war. The play brilliantly captures the crippling tension between the heroic narratives that are demanded of those who survive and the abiding trauma that comes from silencing war’s true horrors. It also shrewdly intimates how that unresolved, even unresolvable, tension percolates through the generations. Each of the play’s scenes is arresting, potent, an exquisite balance of tragedy and comedy. Yet My Sister Jill ends as a series of dazzling moments that fail to mesh into a compelling whole.

The family at the heart of the play – parents Jack (Ian Bliss) and Martha (Maude Davey), and their five children – seem, at first glance, to be a bundle of laughter and love. They play at water fights, dashing around the back garden of their decaying weatherboard house (design by Marg Horwell), and they run amok with firecrackers (vividly realised by the sound and lighting team of Kelly Ryall and Rachel Burke). If a game, however, takes an unexpected turn, Jack’s temper cracks like lightning. He sneers at his children, dismisses his wife, takes off for the pub and drinks. And drinks.

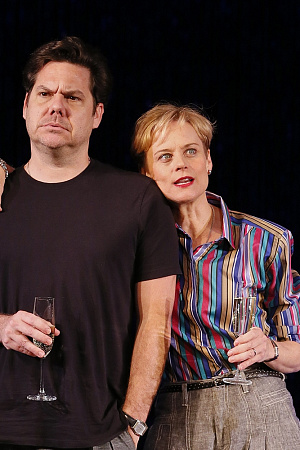

Maude Davey as Martha and Ian Bliss as Jack (photograph by Sarah Walker).

Maude Davey as Martha and Ian Bliss as Jack (photograph by Sarah Walker).

The children are a tight unit, a rough and wry distortion of the von Trapp siblings. Led by their bold elder sister Jill (Lucy Goleby), they realise there is strength in numbers. Their father might be able to pick them off one by one, but confronted by a crowd of them – he insists twins Mouse (Zachary Pidd) and Door (Benjamin Nichol) not stand so close together, constantly reminding them they are ‘not Siamese’ – his control of them, his insistence that they bend to his irrational demands, is undermined.

Jill is the first of the children to rebel, and Golby embodies her with both a lofty adolescent defiance and a keen intelligence (she’s first in her class at school and writes, according to her teacher, the ‘best compositions ever’). Her war-cry of ‘He’s a shit’ is eventually adopted by each of the maturing siblings. Only their mother, locked into marriage by both her memories of first love and her awareness that a woman with five children in tow has few options, resists.

Martha knows Jack is ‘a shit’ – the word darts unexpectedly from her lips when she and the children are sitting in a freezing-cold car waiting for Jack to emerge from the pub – but she also knows what he’s been through, what he has sacrificed, and who, without the intervention of war, he might have been. As Martha, Davey is the essence of a postwar housewife, trapped between hope and reality, between the demands of a husband and children, all of whom she loves but who, she knows, cannot love each other. There is in her body, and in her smile, the weariness of a woman who wants to stop, turn back even, but who knows she has no option but to keep putting one foot in front of the other.

The last of the children to pull away from Jack is Christine (Angourie Rice), the youngest of the siblings. Christine wants to be in the thick of the action, to be a fighter in the resistance, a soldier heading to war. She encourages her father to tell his stories of being a POW in Japan, of being one of only two survivors of a torpedoed boat. She shadows him, both physically and in her imagination, playing out the parts as he plays them, prompting his lines when he becomes distracted or forgetful. He is, for her, quite simply a giant of a man, and she is reluctant to see him through her siblings’ eyes. She almost believes she has his measure, keeping him, through his stories – stories which circumvent the worst of his memories – afloat. Rice’s performance is neatly judged. She brings a wide-eyed vibrancy to Christine, capturing all the vigour, wonder, and horseplay that marks childhood.

One of the standout features of the production is its portrayal of the children. Cornelius’s script and Dee’s direction afford scenes of uproarious fun (Jill experimenting on the twins, trying to discover the degree of telepathy that exists between them) and deep misery (Johnnie’s regular beatings for wetting the bed). There is almost a hyper-reality to these moments, an effect enhanced by Cornelius’s script which, as has become her habit, is embedded with rhyming lines.

Ian Bliss, Lucy Goleby, Maude Davey, James OConnell, and Angourie Rice in My Sister Jill (photograph by Sarah Walker).

Ian Bliss, Lucy Goleby, Maude Davey, James OConnell, and Angourie Rice in My Sister Jill (photograph by Sarah Walker).

While its depiction of children whose family life has been marred by their father’s experience of war is powerful, My Sister Jill is less successful in charting the transition of those children into adulthood. The necessary tonal shift is not as marked as it needs to be and Cornelius’s rhymes, in adult mouths, often sound trite, limiting any sense of authenticity in the dialogue.

James O’Connell’s subtle rendering of Johnnie’s progression from pitiable boy to a young man teetering on the edge of becoming something inherently pathetic is effective. So too Pidd’s evocation of the adult Mouse. Conscripted to fight in Vietnam, he returns home only to withdraw into the same dark hole within which his father exists.

The other siblings are given less to work with. We can regret the choices that have denied Jill her bright future and understand the disillusion that forces Christine to detach from her parents, but Cornelius seems uncertain what to do with these newly minted adults once they are out of range of their father’s anger. The play’s energy dwindles rather than builds, Jack’s repetitious blustering losing its dramatic effect.

Perhaps that is Cornelius’s point, that these are lives that can only fall away, recede. Yet the play’s title explicitly invites comparisons with George Johnston’s classic Australian novel My Brother Jack (1964), the story of two brothers whose lives are defined by the ‘formless shadow of disaster’ cast over them by World War I and concretised by the violence of their father, a Gallipoli veteran.

My Brother Jack’s revelation of what journalist Paul Daley calls an ‘an alternative narrative history’ of Australia underscores what Cornelius’s play lacks. My Sister Jill seems strangely unmoored from its social and political context, the world beyond the confines of the family’s home only filtering into the action when Jill tags along with anti-war protests or when Martha, Jack, and the twins are glued to the television watching the Vietnam conscription lottery.

There is also the absence of a second act the play seems to demand. Only by watching one or other of these children as they make their way in the world – as they experience the second act of their own lives – can we comprehend the full weight of the burden they bear and how their response to that burden shapes their future. As Johnston’s novel demonstrates, such a perspective translates one family’s particular story into something inherently universal.

Ultimately, My Sister Jill is stymied by Cornelius’s uncertainty as to whose story this is and – when the tightly woven family begins to unravel – whose thread she needs to follow. Had her focus held on the combative Jill and the tragedy of her unrealised promise, or the disenchanted Christine, this play may have become something more profound than the sum of its splendid parts.

My Sister Jill (Melbourne Theatre Company) continues at the Southbank Theatre until 28 October 2023. Performance attended: 28 September.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.