Nosferatu

‘What do vampires mean?’, asks playwright Keziah Warner in the writer’s notes for her new show, Nosferatu. It’s not a rhetorical question, Warner has already provided some options: ‘Love, death, sex, money, power.’ Her iteration of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 classic at Malthouse Theatre has all options in mind. While ambitious and technically spectacular, it is a show that struggles to get a read on its source material.

Do vampires need to mean something? What is meaningful if not the ability to scare audiences for more than one hundred years, as Murnau’s totem of German Expressionism has? This is not to say that Murnau’s film is without meaning. Rather that its way into attaining meaning is through affect. Count Orlok, one of the first vampires put on film (Murnau’s way of avoiding a copyright claim from the estate of Bram Stoker) remains a terrifying monster. Cadaverous, animalistic, he lacks the suave disposition of Bella Lugosi’s Count Dracula, as well as his air of authoritative strength. But Murnau trusts the fear-inducing novelty of Max Schreck’s performance, and his choices as a filmmaker reflect a confidence in Schreck’s potential to terrify. The longevity of Nosferatu: Symphony of Horrors can be attributed, in part, to Murnau’s understanding of Stoker’s novel as well as the faith he puts in Schreck’s ability to bring new fears and thus new meaning to it.

L-R Keegan Joyce and Sophie Ross (photograph by Pia Johnson)

L-R Keegan Joyce and Sophie Ross (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Warner’s Nosferatu offers numerous angles from which to read the story and the monster within it, but it struggles to ground these readings in any clear idea of, or trust in, its source. We are in Bluewater, Tasmania, a regional town gone to seed after a local copper mine closed down. Its dwindling population is struggling. Local doctor Kate (Sophie Ross) cannot secure funding to continue her practice. Journalist Ellen (Shamita Siva) feels herself at a dead-end in her career. Tom (Keegan Joyce) and the town’s mayor, Knock (Max Brown) struggle to come up with ideas to save the town.

Tom receives a mysterious letter from Count Orlok (Jacob Collins-Levy), a billionaire living in a slice of Transylvania at the centre of Sydney. Orlok wants to invest in Bluewater. As Tom makes his way to Orlok’s estate, we encounter a litany of Gothic tropes: baying wolves, misty forests, religious locals. ‘Are there dingos in Sydney?’ Tom quips to his girlfriend over voicemail at the sound of high-pitched howling. It’s a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of the antiquated nature of the genre’s conventions. Much of the show’s first half works in this way: a trope of the vampire canon will be ironically named for a knowing audience in ways that expose the weaknesses of its predictable, Eurocentric plot devices and archetypes.

In scene after scene, actors are made to over-explain, and so implicitly apologise for, the Gothic conventions playing out before them. Tom sends a letter to Ellen, and her response is to bemoan the outmoded nature of the artform. A surreptitious demonic text that characters repeatedly return to throughout the show is similarly cast as de rigueur. Over time this conceit reads as an attempt to resolve holes in the story and the genre it is part of, accentuating its weaknesses for laughs. What results is a tension the show struggles to resolve as characters poke fun at tropes that they must inevitably subscribe to in order to drive their story arc and propel the show’s action.

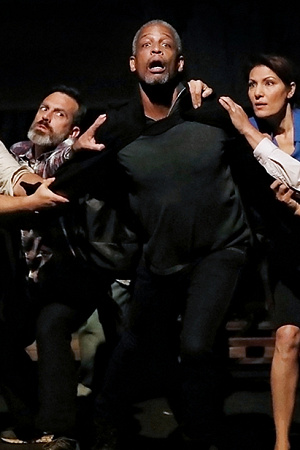

Nosferatu (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Nosferatu (photograph by Pia Johnson)

The price of establishing one’s genre as something to be playfully parodied is that it becomes difficult to accept the show and its characters when they ask us to take these conventions seriously. A lumbering shadow creeps along the back wall towards Tom in a pose taken from Murnau’s film: a bent back, sharp talons reaching outward. It’s an evocative image, one of many created by Paul Jackson’s lighting design and Romanie Harper’s set. But it’s hard to accept or share in Tom’s ensuing panic after the count and his estate have been introduced as the butt of a knowing joke rather than a real threat. The tableau’s emotional potential is compromised by a script that does not appear to have enough faith in the genre.

With crimson curtains, monochromatic lines, and six ominous doors at the back of the stage, Harper’s set design is German Expressionism via Twin Peaks, evoking the bureaucratic horrors at the show’s heart. Composer Kelly Ryall’s score flits expertly between ominous choral-based and Theremin-like compositions and more bombastic intrusions of sudden sound. The show’s technical accomplishments cannot be overstated, and director Bridgette Balodis ensures that these moving parts work seamlessly. But too often these elements purport a fealty to the show’s genre that its script contradicts.

Various attempts to modernise the show’s source text are interesting but too often read as an attempt to legitimise a genre it does not believe can stand on its own. Collins-Levy is the perfect Count Orlok, hitting his elegant stride in the latter half of the show in tightly wound two-hander scenes that allow him to display his charisma with melodramatic abandon. Until then, he struggles to breathe life into a count put forward as a caricature of the toxic developer consumed by a thirst for capital. The magnetism he begins to exert over the townspeople of Bluewater is less supernatural and more a testament to absolute power corrupting absolutely. The ‘plague’ he brings is one of a settler-colonial mentality; a plundering of the land that generates fertility on the back of the bodies of its inhabitants (cursory references to Tasmania’s colonial history offer particularly jarring asides).

While interesting, the show introduces many of these potential topical allegories with an explicitness that gives them little room to grow over the course of its lumbering 100-minute runtime. One is left wishing the show had given its audience more credit, allowing them to find meaning in its fear-inducing moments and monstrous characters without needing to be told what that meaning is. Things pick up in the show’s second half when it focuses on the complex sexual dynamics endemic to the vampiric tradition in ways that prioritise subtext. As Ellen and Tom find their BDSM role play turning to questions of emotional cheating, Warner makes use of genre conventions in earnest. Here, flourishes of pastiche and Grand Guignol-style spectacle exacerbate real character beliefs, fears, and objectives rather than contradict or ironise them. The result is effective and often terrifying.

‘Do you believe in God?’, asks Count Orlok as Tom brandishes a wooden crucifix at him towards the end. Without faith, the symbol’s power dulls, Orlok tells him, leaving behind a bit of empty iconography that fails to affect him. It’s one of many evocative subversions peppered throughout this version of Nosferatu that has some teeth to it. It’s also the perfect summary of the problems which many such subversions encounter – a problem not of meaning, but of faith.

Nosferatu (Malthouse Theatre) continues at the Merlyn Theatre until 5 March 2023. Performance attended: 15 February.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.