Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media

Ask the average person what they picture when they hear the name ‘Andy Warhol’ and they will likely mention Campbell’s Soup Cans, Marilyn Monroe, or Elizabeth Taylor. The Art Gallery of South Australia’s exceptional new exhibition ‘Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media’ reminds us that such ubiquitous images of Pop Art are but one aspect of Warhol’s oeuvre. The show demonstrates throughout how technologies of still and moving image were integral to Warhol’s work over the course of his prolific but abbreviated career.

This is a first for Australia, but also a landmark in global Warhol exhibitions, perhaps the first major show in nearly a quarter century focusing exclusively on photography. Ten years in the making, the exhibition’s depth of focus is everywhere on display in Julie Robinson’s sophisticated and intelligent curation. AGSA’s timely intervention is as serious and smart as it is terrifically fun – a vanishing rarity for gallery shows of this calibre and scope; it helps us to see, without ever forcing the point, that Warhol’s approach to photography anticipated so much about the dynamics of the social media ecosystem that has been transforming the world for the past decade.

Bob Adelman, Andy Warhol on the red couch at the Factory, 1964, New York, Courtesy of Bob Adelman Estate

Bob Adelman, Andy Warhol on the red couch at the Factory, 1964, New York, Courtesy of Bob Adelman Estate

Robinson and her team have produced a career-spanning overview of Warhol’s photographic practice, but the show also offers visitors a vibrant sense of the way still and moving photography functioned as a defining medium in the wider artistic milieu centred around The Factory. The first image we encounter is not in fact by Warhol, but an autographed publicity photo of child actor Shirley Temple with a dedication to the future artist. This memento might appear to speak to the obsession with celebrity that characterised much of Warhol’s screen-printing work, but it is more usefully understood in terms of self-mythologising (or, in Temple’s case, the aggressive mythologising of the movie industry), mass reproduction, and the significance of the found image to Warhol’s screen-printing work.

In the adjacent room, visitors are confronted by one of the larger-than-life-size screen-print paintings of Elvis Presley that Warhol produced from a publicity still. Beneath the photographic referent, Robinson has juxtaposed Elvis at the Ferus, a film that Warhol made in 1963 on the occasion of his Elvis paintings’ show at the influential Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. The marvel of these three minutes of black-and-white 16mm is that Warhol is not producing just a home-movie travelogue of his works’ exhibition, but a further expression of the impulse driving the work, exploring in dizzying pans and ludic jump cuts his fascination with repetition and reproducibility, with the commodification and objectification of the performer depicted in the work, a man who seems to exist always in a state of performance that obscures whatever might remain of the core self.

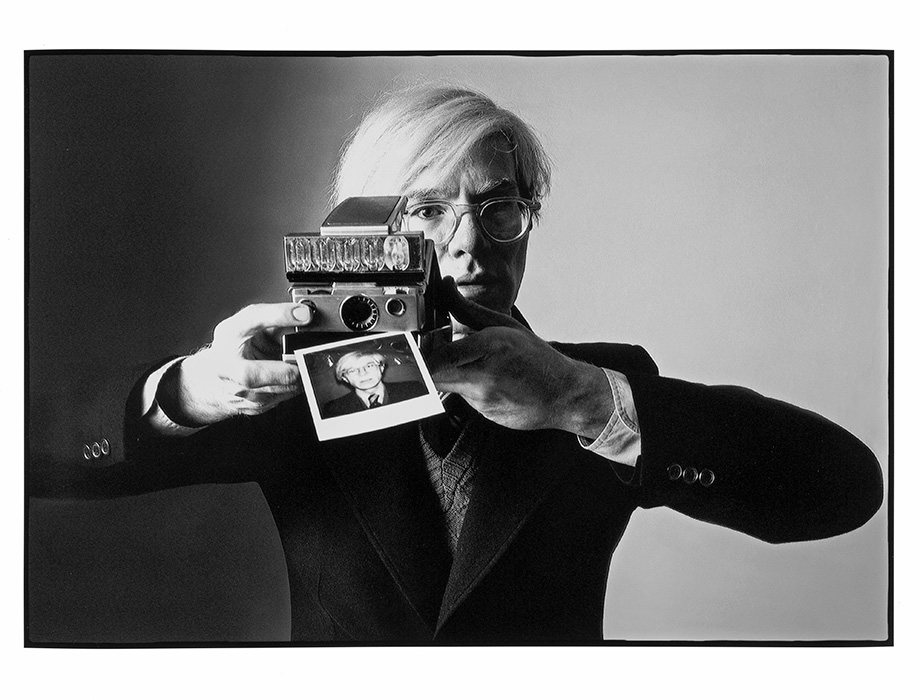

So for Elvis, so for Warhol. The studied mystification of the ‘true’ self is one of the key problems that this exhibition frames so brilliantly. It offers in almost equal measure a multifaceted portrait of Warhol as artist and as private person (as much as he might ever have been truly private), alongside a compelling selection of Warhol’s screen prints, editioned photographs, unique polaroids, films, and videos. The great revelation for me was much less well-known work from the last years of Warhol’s life, including a series of non-editioned street photographs from the 1980s, and a selection of his stitched-together photographs (multiple prints of the same image sewn into grids). These subtler, more obscure works hint at a Warhol who is arrestingly unostentatious, and remind us in staggeringly different ways of the importance of the intertwined impulses of chance and repetition in the practice.

How does one reconcile the quiet, Atget-like preoccupation with uncanny details like mannequins and neglected shop window displays, or attention to the line of a shadow on urban pavement, a collection of protest signs, a lover seen only from the back and below the waist strolling on a beach, or the unassuming double portrait of Dolly Parton and Keith Haring with, from the same period, the almost Dadaist freneticism of Andy Warhol TV and its wild use of early 1980s video animation, a montage of fashion shows, and awkward but no less endearing clips of Warhol flirtatiously interviewing actors and models? The answer, perhaps, is that the impulses behind such a range of practice and intervention in popular culture cannot be reduced to a single formal or aesthetic logic. What the AGSA show instead offers is a portrait of the artist that tries to reflect as many facets of the practice and the person as can be encompassed by a single exhibition.

Andy Warhol, Liza Minnelli, 1978, New York, V.B.F. Young Bequest Fund 2012, Art Gallery of South Australia © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol, Liza Minnelli, 1978, New York, V.B.F. Young Bequest Fund 2012, Art Gallery of South Australia © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Both times I visited the show I came out of it deeply moved and certain of two things: the assertion by photographer Peter Hujar that Warhol was the Leonardo of his age is not an overstatement (even as it says as much about the age as it does about Warhol’s importance); and that, behind the glitter, glamour, and outrageous playfulness, there was a profound sense of melancholy – not only in the last decade of Warhol’s life, but almost from the start. We see the longing for something or someone in his brother John’s early portrait of ‘Andy Warhola’ (as he then was), and throughout images from the following decades an ever more conscious management and curation of his self-image. Behind the revelry is effort and industry; as Lou Reed sang in the tribute album to Warhol, Songs for Drella, ‘The most important thing is work.’

One of the pleasurable coups de théâtre the exhibition mounts is to cover the walls of the first full room with metallic silver paper that evokes the ‘Silver Factory’ – Warhol’s industrial loft space decorated by photographer Billy Name in the early 1960s and in which we see Warhol working in a photograph by Name from 1964. In this room, the first images one encounters by Warhol himself are disarmingly intimate: a tiny series of photobooth strips from 1963, one set depicting Warhol being theatrically punched, others of gallerist Holly Solomon, collector Ethel Scull, and Claes and Patti Oldenburg clowning for the automated camera. (In another playful touch, AGSA has installed a photobooth at the exit of the exhibition where visitors can have their own strips of images taken, reminding us of the analogue origins of the photographic ‘selfie’.)

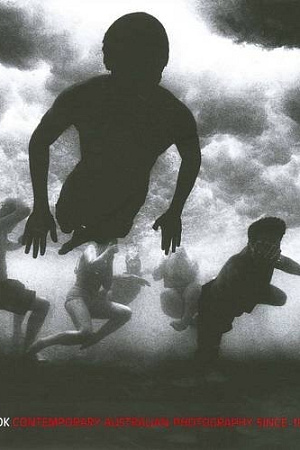

In the same room, Robinson has mounted a display of ten of Warhol’s famous black- and-white ‘screen tests’, including of the artist’s one-time lover John Giorno, as well as Lou Reed, Edie Sedgwick, Bob Dylan, Salvador Dalí, and other Factory regulars. The subjects sometimes look away, stare at the viewer, vamp, cry, or seem to resist the act of filmed portraiture entirely. Several other Warhol film works are also on display, including the chaotic Camp (1965) and uncannily menacing Haircut (1963), colour footage of Warhol’s soulful fellow artist Marisol in Old Lyme, Connecticut, in the early 1960s, and half an hour of the Kennedy children playing on a beach in the early 1970s (these last two, in particular, convey an unmistakable sense of existential anxiety, even crisis).

This is a rare opportunity for the gallery-goer to engage with works that are otherwise nearly impossible to see; Warhol withdrew his films from public circulation in the 1970s, and although one knows more-or-less which films exist, gaining access to them is so difficult that anyone even mildly interested in Warhol should make the effort to see this show. As with his still photography, the films and videos repeatedly demonstrate Warhol’s readiness to experiment with technologies and media, but also to present to the world an unabashedly queer sensibility. Haircut, for instance, is at one level merely a document of what its title describes but becomes a chiaroscuro multiple portrait that inserts itself into a canon of visual art, even recalling Caravaggio in its use of light and shadow and in its abundant homoeroticism. The most unsettling of the film’s subjects, Fred Herko, repeatedly breaks the fourth wall, engaging the gaze of the filmmaker but also staring back at every viewer who encounters him down through the years, demanding that we register both his vulnerability and his menacing power.

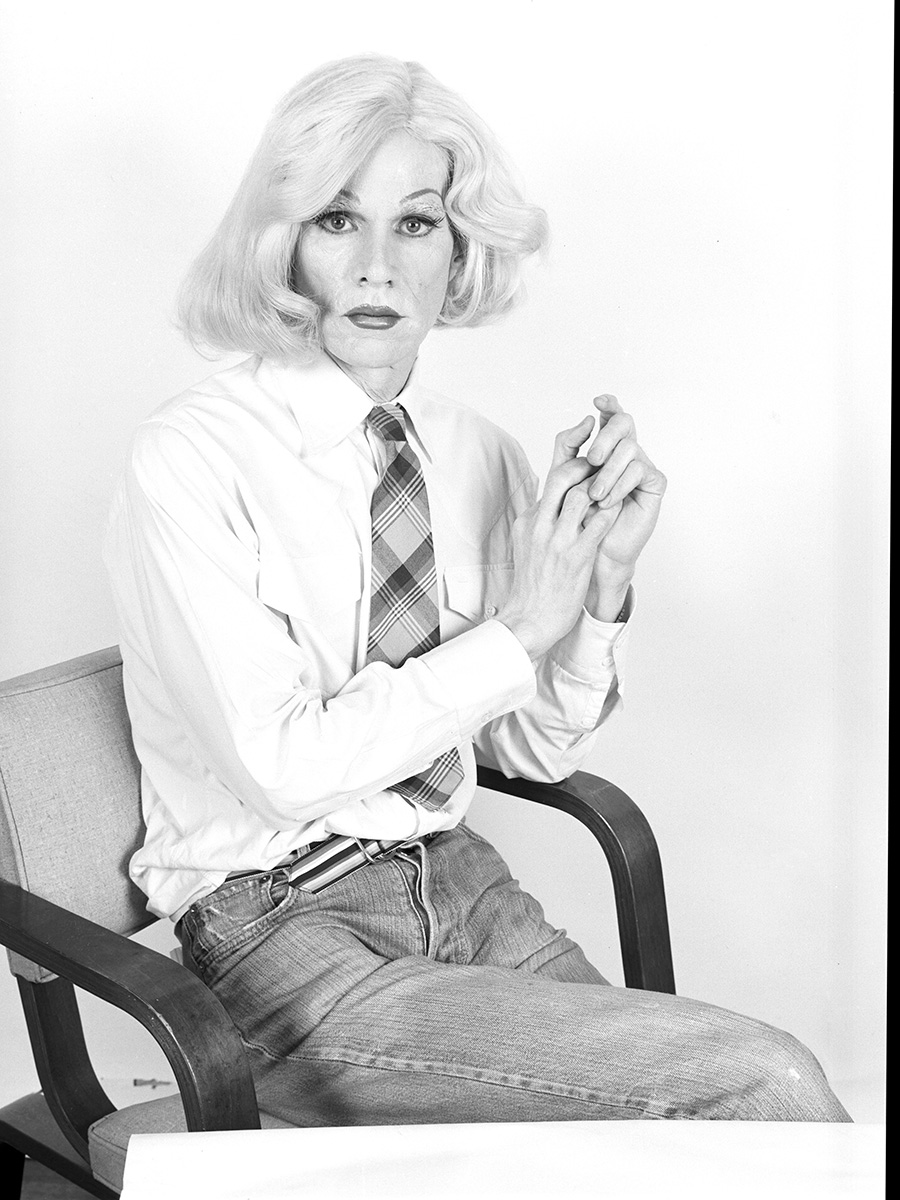

Christopher Makos, Altered Image from the portfolio Altered Image: Five Photographs of Andy Warhol, 1981; published 1982, New York; Purchased 1982, National Gallery of Australia © Christopher Makos

Christopher Makos, Altered Image from the portfolio Altered Image: Five Photographs of Andy Warhol, 1981; published 1982, New York; Purchased 1982, National Gallery of Australia © Christopher Makos

While queer Abstract Expressionists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns might be said to have obscured their sexuality through a practice of non-figuration (or evasively symbolic figuration), Warhol, for all of his maybe-I-am-maybe-I’m-not dissembling about his sexuality in the media, was consistently presenting work that could not be mistaken for anything other than the practice of a queer artist. Whether that amounts to depicting drag and trans performers (as in the moving series Ladies and Gentlemen (1975), which the show pairs with some of the original reference polaroids for the screen-prints), or homoerotic polaroids of male nudes, or the moment in Camp when Warhol collaborator Gerard Malanga recites a poem about being ‘buggered’ by a Cornell University student, or the sustained fixation on queer icons like Liza Minnelli and Jackie Kennedy, or Christopher Makos’s melancholy images depicting Warhol himself in drag (though Makos insists this was not what is being figured), one leaves the exhibition convinced that Warhol moved global culture forward by mainstreaming an extravagant range of queer sensibilities. Sometimes almost blandly commercial (as in the celebrity images), in other moments radically subversive and risqué, Warhol’s outpouring of art surely stands as among the most significant engines of social representational transformation in the last seventy years.

Through the lens of photography, this exhibition offers a taste of many central aspects of Warhol’s work without diluting the significance of his photographic practice in particular. For Australian audiences, there is certain pleasure in seeing six images of Warhol’s only two portrait subjects from this country: four screen-prints of philanthropist and Australian editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine, Henry Gillespie (who also recorded a short video for the show), and two of the late arts benefactor Loti Smorgon. This is not only a major show that brings together works from all over the world, but one that is not travelling. If there is any disappointment, it is this, but also that there is no catalogue for the exhibition, despite the curatorial team’s best efforts. What a pity that there will be no permanent record of the important work it is doing for two brief months this year. (I wrote an essay for the intended catalogue, which now appears on the AGSA website.)

I came away from my visits to the show feeling that with any justice, or better luck, Warhol might still be with us (as his collaborators Makos, Duane Michals, and Stephen Shore – all with works in the show – continue to be). We can only imagine how he might now be responding to the evolution of photographic technology and the bewildering visual vocabulary of our time. What he left behind continues to prompt us to reflect on questions of subjectivity, the gaze, agency, and the effects of objectification that mark Warhol’s photographic work from the very start.

Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media continues at the Art Gallery of South Australia until 14 May 2023.

Correction

An earlier version of this review referred to Andy Warhol's 1963 film as Elvis at Ferus instead of Elvis at the Ferus.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.