'Australian Dreaming'

Stan Grant’s comment on the prolonged booing of the Australian Rules football star Adam Goodes – featured in Daniel Gordon’s new documentary, The Australian Dream (produced by Grant himself) – has attracted much interest, including more than one million hits on one website:

We heard a sound that was very familiar to us. We heard a howl. We heard a howl of humiliation that echoes across two centuries of dispossession, injustice, suffering, and survival. We heard the howl of the Australian dream and it said to us again, ‘You’re not welcome.’

Perhaps it was coincidental, perhaps the crowds simply grew tired of jeering, perhaps it was the speech itself (delivered in October 2015 at the Ethics Centre). Whatever the reason, public sentiment began to turn after Grant’s speech. People wore Goodes’s guernsey number and waved signs and banners saying ‘We love you Goodesy’. Celebrities filmed messages of support.

Goodes, having become so broken and dispirited as to remove himself from football, returned to play the last few games of the 2015 season. The booing resumed. Unlike a Sydney teammate also entering retirement, Goodes chose not to be chaired from the ground.

Grant tells us that because of Goodes a new space has opened up, one that will loosen the chains of history so that we might ‘find belonging, find each other’. I’m not so sure.

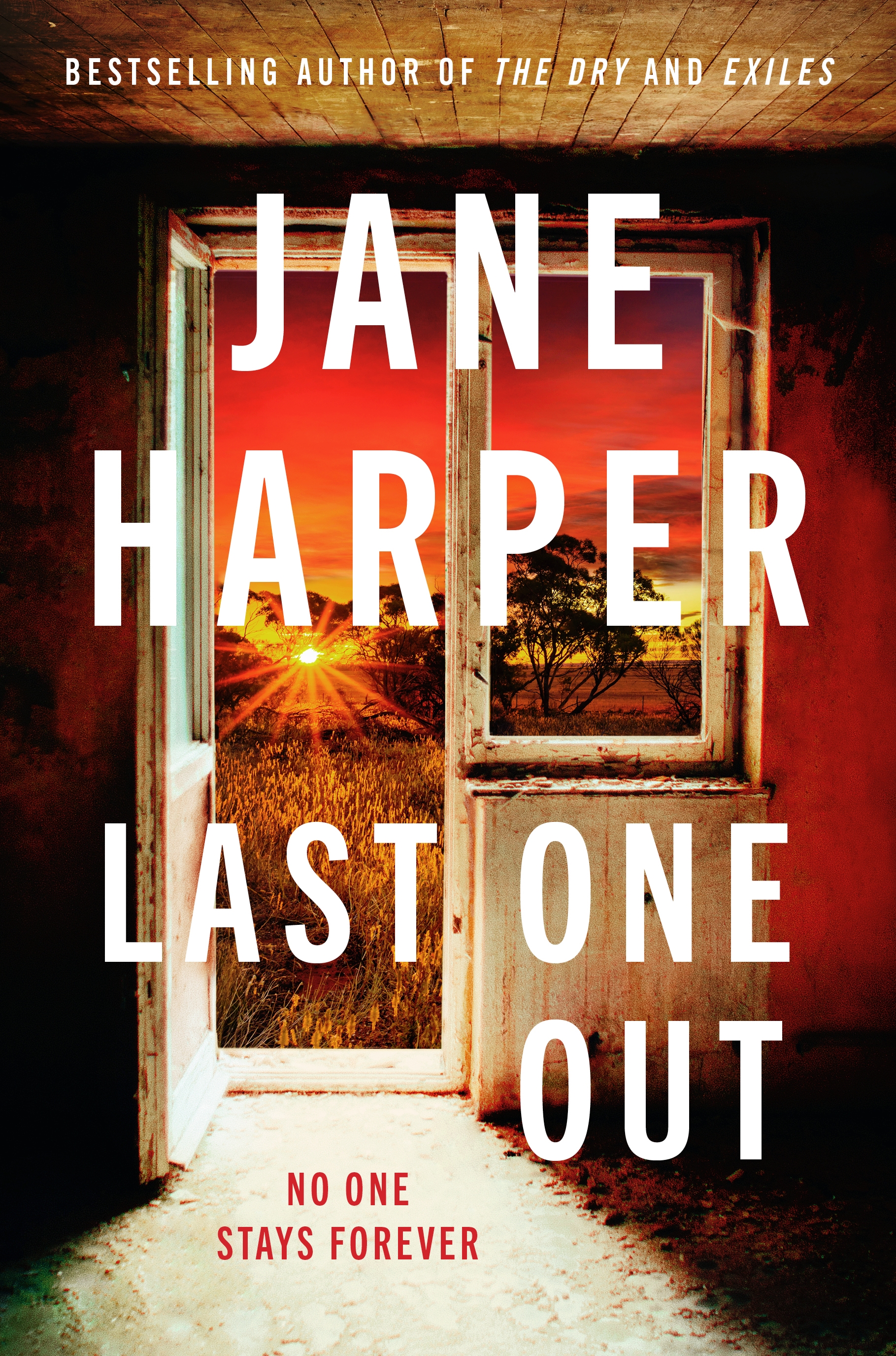

Adam Goodes in a still from The Australian Dream (photograph via Madman)

Adam Goodes in a still from The Australian Dream (photograph via Madman)

Earlier in the documentary, Goodes says he doesn’t know much about what it means to be Indigenous. Oh, but he certainly does. He’s been insulted and rejected. He’s been ‘encouraged’ to lay low and become invisible in order to fit in. As for his critics, as Gilbert McAdam says, ‘What would they know?’

To be Indigenous is often to experience racism and sometimes something even more. You might call it a structural thing: the insistence on a certain power relationship between Australia and its Aboriginal people that is perhaps the defining characteristic of Australian identity. Some have attributed this insistence to an antipodean Occidentalism, even a settler–colonialist psychosis, the result of a continuing collective insecurity and subsequent need for fragments of the mother colony to be bound together by the threat of the Other. It’s an ailment as old as the nation itself, and one that apparently makes it so hard for Aboriginal people to be fully accepted in Australia? It might help explain the treatment of Goodes and the rejection of The Uluru Statement, which says, in part: ‘The dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.’

Goodes says he didn’t know much Aboriginal culture and identity. The legacy of a history of oppression can mean that, for many individuals, Aboriginality is just ‘broken glass and stray dogs’. Both men say that it’s hard to know what to do when the ‘smart asses’ call you the names a racist society makes so easily available: boong and coon and nigger and darky and ape. There is the heft of vicious history behind all those terms.

What to do? Ignore them? But it won’t go away, and your children and family and friends remain targets. Stand up and call them out? To do that you need supporters or you end up as isolated as Goodes.

Ironically, Goodes tell us it was the Sydney Swans ‘Bloods’ culture that gave him a sense of identity and the aspiration to be the leader he became, both within his team and within Australian Rules football as a whole. When his academic application to Indigenous Studies made him realise the injustice and oppression of his history, he continued to lead. He called out racism and then spoke compassionately about the individual in question, explaining that it was not her choice as such but the result of a discourse in which she was immersed, one that maims us all.

The booing grew louder.

Stan Grant in a still from The Australian Dream (photograph via Madman)

Stan Grant in a still from The Australian Dream (photograph via Madman)

Another response to racism is to fight. Many Aboriginal people’s life experience teaches them that an effective response to racism is violence. Flog the perpetrator. Nothing else will get it to stop. Goodes couldn’t do that, though his ‘war dance’ was perhaps symbolic of such an approach. In his case – one against thousands – it only exacerbated the problem. The howling mob rose against him, eager for any excuse for self-righteous offence, keen to put him in his place. But that dance also represented an attempt to draw upon his heritage for comfort, for healing, for a solution to the structural dimension of racism.

Goodes’s return to ancestral Country is clearly an attempt to draw upon his pre-colonial heritage for solace, if not a solution. It works, after a fashion. It helps him to return to football. I am not claiming the dance or the journey as substantial examples of connection with Indigenous heritage, but they do signal a new direction.

There’s plenty of evidence highlighting the potential for such reconnection to heal individuals and communities. There’s a growing realisation that such heritages are also important denominations in the currency of identity and belonging for all Australians. Look at the material used to express Australia’s imagery internationally. Look at the rise of dual naming, the increase in Welcomes to Country and the use of language therein. Look at the popularity of Indigenous tourism, films, and literature.

True, in many cases this heritage – in its classical sense – is frail and endangered. And true, in at least some cases, ‘mainstream Australia’ appears to desire heritage but not its custodians. It is the reconnection and recovery of such heritages by home communities, and their empowerment through controlled sharing of them, along with a readiness to challenge ossified certainties, that will provide a more nuanced sense of national identity and will close the door on the hysterical manifestation of national psychosis and Indigenous structural powerlessness that this compelling documentary reveals.

Not a howl – a Voice.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.