Information (254)

Children categories

Thanking our Partners (14)

Australian Book Review is assisted by the Australian Government through Creative Australia, its principal arts investment and advisory body, and is also supported by the South Australian Government through Arts South Australia. We also acknowledge the generous support of our university partner, Monash University; and we are grateful for the support of the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund, Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM), the Sidney Myer Fund, Australian Communities Foundation, Sydney Community Foundation, AustLit, Readings, our travel partner Academy Travel, the City of Melbourne, and Arnold Bloch Leibler.

View items...Jolley Prize Frequently Asked Questions

I don’t live in Australia and I am not an Australian citizen. Can I still enter?

Yes, you can. Anyone can enter the Jolley Prize. But all stories must be written in English.

I’m interested in the Jolley Prize but don’t know much about it. How can I familiarise myself with the competition?

This is the fifteenth time that Australian Book Review has presented a short story prize. Past issues containing the shortlisted and winning stories are available for subscribers to read online in our online archive or to purchase in hard-copy from our online store.

Click here for more information about past winners.

What is the entry period for the 2025 Jolley Prize?

Entries for the 2025 Jolley Prize are open from 10 February 2025 to 5 May 2025. The three shortlisted stories will be published in the August or September 2025 issue and the winner will be announced later in the month of publication.

Is there a set theme or topic for the Jolley Prize?

No, stories can be on any subject and in any style.

What is the word limit for the Jolley Prize?

Stories must be between 2,000 and 5,000 words in length.

Can I submit a non-fiction story?

No, the Jolley Prize is for fiction, although entries can be inspired by real life. ABR also presents the annual Calibre Essay Prize, which is intended for non-fiction essays.

Can I enter multiple stories in one entry?

No. Separate entries must be made, and transactions paid, for each story entered into the Jolley Prize. This is to ensure that a record is kept of each story entered, and also to ensure that payment is successfully made for each.

Is there a limit to the number of stories I can enter?

No, but as stated above, each story must be entered and paid for separately, as individual entries.

Can I enter my story using a pseudonym?

Works must be entered under a real name. Internally, ABR ensures that names are not associated with essays for the judging process. Essays are strictly blind judged. Should your work be shortlisted and named, pseudonyms will not be acceptable. For publicity reasons, all shortlisted authors must be publicly named.

I have written a story with someone else. Are we eligible to enter the Jolley Prize?

No, stories entered in the Jolley must be written by one individual author.

My friend/relative has written a story, can I enter it on their behalf?

No, stories must be entered by their authors.

Are translated stories eligible for entry in the Jolley Prize?

No.

To be eligible for entry in the Jolley Prize stories must not have been previously published, what constitutes ‘publication’?

Publication includes, but is not limited to, publication in print and online (for example in a journal/magazine/anthology or on a website). Publication on a personal blog/website constitutes publication. If a story has been written and assessed as part of a writing course but has not been distributed further, that does not constitute publication.

My story was shortlisted/commended for another prize, can I enter it in the Jolley Prize?

If your story was shortlisted/commended for another prize but was not published, then it can be entered in the Jolley. Please contact us if you are unsure about eligibility.

Can I submit the work I have entered in the Jolley Prize elsewhere while I await notification?

Initially, stories may be entered in other prizes or submitted to other publications. However, if your story is longlisted in the Jolley Prize you must confirm eligibility and exclusivity – i.e. you must either withdraw it from the other outlets/prizes or withdraw it from the Jolley Prize.

When will longlisted authors be contacted?

Notification will take place in July or early August 2025. Longlisted authors who are not shortlisted will be notified in July/August and can then offer their stories elsewhere. See our Terms and Conditions for more information.

When will non-longlisted authors be notified?

Notification will take place in July or early August 2025.

When and where will the shortlisted stories be published?

The three shortlisted stories will be published in the August or September 2025 issue of ABR and on the ABR website.

What is the prize money for the 2025 Jolley Prize?

The Jolley Prize is worth a total of $12,500 (AUD). This will be split between the three shortlisted authors in the following way:

First Prize: $6,000

Second Prize: $4,000

Third Prize: $2,500

Can I pay the discounted entry fee?

Current print subscribers and yearly digital subscribers may pay the discounted entry fee of AU$20 per entry. Non-subscribers pay AU$30 per entry. If you would like a print and/or digital subscription to ABR, click here.

Alternatively you can purchase a yearly digital subscription to ABR with your entry for the combined price of AU$100. Your sign-in details will be automatically sent to you by email, and you will be entitled to enter any additional stories at the discounted rate. We also offered combined print subscriptions and Jolley Prize entry packages. A full list of entry rates appears below:

Online entry (current ABR subscriber) - $20

Online entry (standard/non subscriber) - $30*

Online entry + 1-year digital subscription - $100

Online entry + 1-year print & digital subscription (Australia) - $130

Online entry + 1-year print & digital subscription (NZ and Asia) - $220

Online entry + 1-year print & digital subscription (Rest of World) - $240

Note: Print subscribers must provide their subscriber number to be eligible for the discounted rate (this can be found on the flysheet sent out with the magazine, or on renewal notices – alternatively, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will provide you with your subscriber number). Likewise, yearly digital subscribers must provide the email address with which they registered the online subscription.

Can I pay with PayPal?

At this time we are accepting credit card payments only – Visa and MasterCard. We do not accept Amex.

Will I receive confirmation of payment?

Yes, once you have submitted your online entry and payment form, you will receive a confirmation email at the email address you supplied in the form. Keep a copy for your records. If you cannot find the confirmation email, be sure to check that it has not gone to your spam or junk folders.

Can I enter by post?

No, entries must be submitted online.

Who are the judges this year?

The 2025 judges are Julie Janson, John Kinsella and Maria Takolander.

Will you give me feedback about my story?

Unfortunately, we don’t have the time or resources to comment on individual stories.

How should I format my story?

Entries should be presented in 12 pt font size. The pages of stories should be numbered. (Please note, if you realise that you have submitted your story without the preferred formatting this will not disqualify it from the Prize.) The author’s name must not appear in the body of the entry or in the name of the digital file.

What file type is acceptable?

We accept Word documents only.

Where can I find the complete Terms and Conditions of entry?

These can be found here.

How can I stay in touch with news about the Jolley Prize?

If you have provided us with a current email address we will contact you with news about the Jolley Prize. Another way to stay up-to-date with news about the Jolley Prize and other ABR prizes and events is to sign up to our online newsletters. Alternatively you can follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

My question isn't answered here, what should I do?

If you have a question about the Jolley Prize that isn't answered here, or in the entry guidelines, please contact us via the comments facility below and we will respond when we can.

Additional Info

-

Sponsor Logo

1-final.jpg)

- Sponsor Website http://www.abl.com.au

Additional Info

-

Sponsor Logo

- Sponsor Website http://arts.sa.gov.au/

Additional Info

-

Sponsor Logo

- Sponsor Website https://creative.gov.au/

The ABR Patrons

The ABR Patrons

ABR gratefully acknowledges the support of its Patrons

Generous donations from Patrons have transformed Australian Book Review in recent years, with major benefits for Australian writers and readers. These donations have enabled us to expand our programs, to diversify the magazine, and to be more ambitious and outward-looking. Most importantly, we have increased our payments to contributors at a time when paid freelance opportunities are relatively few. Our three literary prizes, our several Fellowships, and ABR Arts are only possible because of cultural philanthropy. With support from Patrons we look forward to preserving and improving the magazine for many years to come. In recognition of our Patrons’ continuing generosity, ABR records multiple donations cumulatively.

If you wish to discuss the ABR Patrons Program, please contact Georgina Arnott at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or (03) 9699 8822.

_______________________________

PARNASSIAN

($100,000 or more)

Blake Beckett Fund

Ian Dickson AM

Maria Myers AC

ACMEIST

($75,000 to $99,999)

Morag Fraser AM

OLYMPIAN

($50,000 to $74,999)

Anita Apsitis OAM and Graham Anderson

Neil Kaplan CBE KC and Su Lesser

Ruth and Ralph Renard

AUGUSTAN

($25,000 to $49,999)

Australian Communities Foundation (Koshland Innovation Fund)

In memory of Kate Boyce, 1935-2020

Professor Glyn Davis AC and Professor Margaret Gardner AC

Marion Dixon

Emeritus Professor Margaret Plant OAM

Lady Potter AC CMRI

Mary-Ruth Sindrey and Peter McLennan

Emeritus Professor Andrew Taylor AM

John Scully

Anonymous (2)

IMAGIST

($15,000 to $24,999)

Emeritus Professor David Carment AM

Emeritus Professor Anne Edwards AO

Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM)

Allan Murray-Jones

David Poulton

Peter Rose and Christopher Menz

VORTICIST

($10,000 to $14,999)

Peter Allan

Gillian Appleton

Professor The Hon. Kevin Bell AM KC and Tricia Byrnes

Dr Neal Blewett AC

Helen Brack

Roslyn Follett

Jock Given

Cathrine Harboe-Ree AM

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

Linsay and John Knight

Susan Nathan

Ilana and Ray Snyder

Noel Turnbull

Susan Varga

Nicola Wass

FUTURIST

($5,000 to $9,999)

Kate Baillieu

Professor Frank Bongiorno AM

Des Cowley

Donna Curran and Patrick McCaughey

Professor The Hon. Gareth Evans AC KC

Helen Garner

Professor Emeritus Ian Gust AO (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Dr Neil James

Dr Barbara Kamler

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Pamela McLure

Dr Stephen McNamara

Don Meadows

Stephen Newton AO

Diana and Helen O'Neil

Jillian Pappas (d. 2024)

Judith Pini (honouring Agnes Helen Pini, 1939-2016)

Jill Redner (in memory of Harry Redner, 1937-2021)

Emeritus Professor Roger Rees

John Richards

Dr Trish Richardson (in memory of Andy Lloyd James, 1944-2022)

Robert Sessions AM

Emerita Professor Susan Sheridan and Emerita Professor Susan Magarey AM

Noel Turnbull

Lyn Williams AC

Ruth Wisniak OAM and Dr John Miller AO

Anonymous (3)

MODERNIST

($2,500 to $4,999)

Professor Dennis Altman AM

Paul Anderson

Helen Angus

Australian Communities Foundation (JRA Support Fund)

Judith Bishop and Petr Kuzmin

Professor Jan Carter AM

Joel Deane

Jason Drewe

Jean Dunn

Emeritus Professor Helen Ennis

Elly Fink

Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick

Professor Paul Giles

Steve Gome

Tom Griffiths

Professor Nick Haslam

Michael Henry AM

Mary Hoban

Professor Sarah Holland-Batt

Claudia Hyles OAM

Anthony Kane

Professor Marilyn Lake AO

Professor John Langmore AM

The Hon. Robyn Lansdowne

Alison Leslie

Emeritus Professor Peter McPhee AM

Patricia Nethery

Angela Nordlinger

Barbara Paterson

Mark Powell

Emeritus Professor Wilfrid Prest AM

Professor David Rolph

Professor Lynette Russell AM

Jamie Simpson

Dr Jennifer Strauss AM

Dr Diana M Thomas

Lisa Turner

Dr Helen Tyzack

Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Webby AM

Anonymous (3)

ROMANTIC

($1,000 to $2,499)

Nicole Abadee and Rob Macfarlan

Damian and Sandra Abrahams

Australian Communities Foundation

Jeffry Babb

Jean Bloomfield

Professor Kate Burridge

Dr Jill Burton

Brian Chatterton OAM

Professor Caroline de Costa

Stuart Flavell

Dilan Gunawardana

Associate Professor Michael Halliwell

Robyn Hewitt

Greg Hocking AM

The Family of Ken and Amirah Inglis (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Associate Professor Cameron Logan and Professor Clare Monagle

Hon. Chris Maxwell AC

Dr Heather Neilson

Penelope Nelson

Professor Michael L. Ondaatje

Jane Patrick

Estate of Dorothy Porter

Professor John Poynter AO OBE

Professor Carroll Pursell and Professor Angela Woollacott

Dr Ron Radford AM

Professor Stephen Regan

Dr Della Rowley (in memory of Hazel Rowley, 1951–2011)

Dr Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

Alan Sheardown

Michael Shmith and Christine Johnson

Alex Skovron

Susan Tracey (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Craig Wilcox (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Kyle Wilson

Dr Diana and Mr John Wyndham

Anonymous (1)

SYMBOLIST

($500 to $999)

Robyn Archer AO

Dr Robyn Arianrhod

Michael Clouten

Associate Professor Clare Corbould

Professor Graeme Davison AO

Emeritus Professor Rae Frances and Professor Bruce Scates (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Dr Kerryn Goldsworthy

Professor Bill Green

Paul Hetherington

Barbara Hoad

Dr Alison Inglis AM

Professor Shirley Lindenbaum (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Gillian Pauli

Anastasios Piperoglou

Emeritus Professor Andrew Scott

Tom Simpson

Dr Tangea Tansley

Geordie Williamson

Anonymous (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Anonymous (3)

REALIST

($250 to $499)

Caroline Bailey

Dr Claudio Bozzi and Dr Vivien Gaston

Jan Brazier (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Professor Nicholas Brown (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Margaret Hollingdale

Manuell Family (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Dr Eileen Monagle

Deborah Pike

Professor Emerita Marian Quartly (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

Matthew Schultz

Margaret Smith

Professor Alistair Thomson (ABR Inglis Fellowship)

ABR BEQUEST PROGRAM

Gillian Appleton

Ian Dickson AM

John Button (1933-2009)

Peter Corrigan AM (1941-2016)

Dr Kerryn Goldsworthy

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Dr Ann Moyal (1926-2016)

Peter Rose

Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

John Scully

Denise Smith

Anonymous (3)

Click here if you are interested in leaving a bequest.

2014 Porter Prize winner

Jessica L. Wilkinson wins 2014 Porter Prize

Australian Book Review is delighted to announce that Jessica L. Wilkinson has won the 2014 ABR Peter Porter Poetry Prize for her poem ‘Arrival Platform Humlet’. Jessica receives $4,000 for her winning poem, which was drawn from a field of just under 700 entries.

Australian Book Review is delighted to announce that Jessica L. Wilkinson has won the 2014 ABR Peter Porter Poetry Prize for her poem ‘Arrival Platform Humlet’. Jessica receives $4,000 for her winning poem, which was drawn from a field of just under 700 entries.

Elizabeth Allen, Nathan Curnow, and Paul Kane were also shortlisted, with each poet receiving $833 for their shortlisted poems (‘Absence’, ‘Scenes from the Olivet Discourse’ and ‘VFGA.’ respectively).

The judges were Lisa Gorton and Felicity Plunkett.

‘I am truly honoured that my poem ‘‘Arrival Platform Humlet’’ was recognised in this way and very privileged to be associated with the good name of Peter Porter.’

Jessica L. Wilkinson

Judges' report

‘Judging this prize was difficult, if rewarding, because the number of poems that demanded serious consideration. The judges longlisted more than thirty. After much consideration, we shortlisted four of them. They showed a thoughtful and inventive approach to the traditions that they were drawing on, and achieved a distinctive and memorable poetic vision.’

Lisa Gorton and Felicity Plunkett

ABR gratefully acknowledges the support of Morag Fraser AM

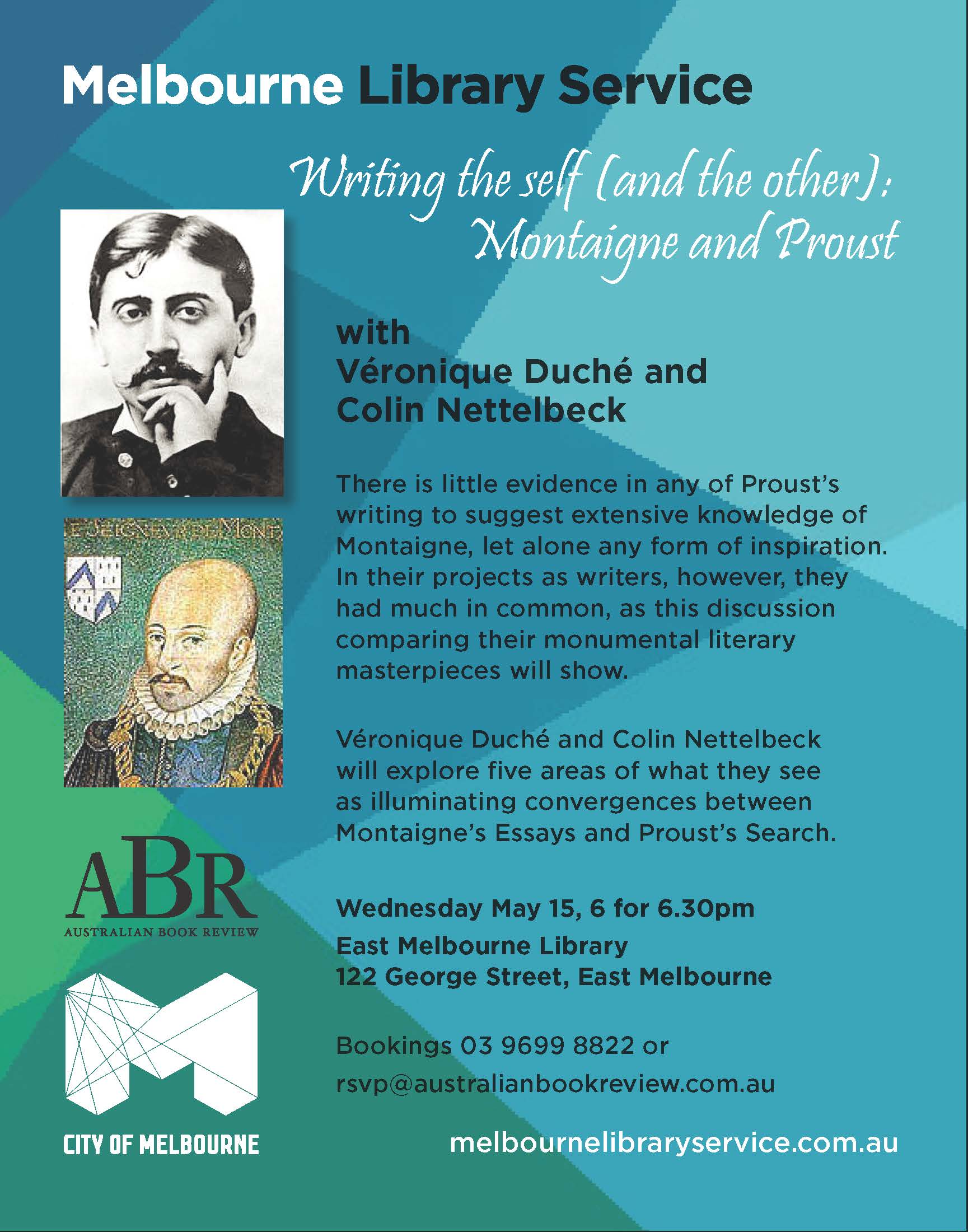

Proust and Montaigne

Proust and Montaigne – Writing the Self, May 15 at 6.p.m

Francophiles, essayists, and Proustians will not want to miss a joint ABR and Melbourne Library Services event to be held in the East Melbourne Library on Wednesday, 15 May (6 p.m.). Noted French scholars and enthusiasts Véronique Duché and Colin Nettelbeck (who reviews Camus’s Algerian Chronicles for us in the May issue) will be in discussion about Montaigne and Proust, with particular references to convergences in their remarkable works. This is a free event, but reservations are essential: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Please note this event is now booked out.

Additional Info

-

Sponsor Logo

- Sponsor Website http://www.creativespaces.net.au

Additional Info

-

Sponsor Logo

- Sponsor Website http://www.copyright.com.au

Subscribe to ABR

Subscribe to ABR

Join the ABR community. We offer a range of subscriptions tailored for individuals and institutions, print readers and online users.

If you are having trouble subscribing, contact us on (03) 9699 8822 or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Digital

Subscribe for as little as $10 per month and receive complete digital access to ABR.

Print + Digital

Subscribe and receive 11 print issues per year as well as complete digital access to ABR.

ABR Arts

Subscribe and receive complete digital access to ABR Arts.

Take Two

Purchase a combined print + digital subscription to ABR and one other Australian literary magazine, including: Overland, Island Magazine, Limelight, Griffith Review, and Westerly Magazine.

Gift subscriptions to ABR

Purchase a full print and/or digital subscription to ABR as a gift for someone.

Purchase single issues

Purchase a single print issue of ABR.

Institutions

Purchase an institutional subscription for your university and/or library.

Universities, government auspices and institutions must contact ABR to set up online access:

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or call +61 3 9699 8822.

Only individual subscribers are eligible to add a digital subscription to their print subscription free of charge. ABR digital subscribers are subject to our Terms and Conditions of Use.

All small institutions, including schools and municipal libraries, can purchase a one-year digital subscription for $150. However, for university libraries, government auspices and departments, national and state libraries and their international counterparts (in terms of status and reach) a one-year digital subscription to ABR costs $550.

To organise an institutional digital subscription please contact ABR by This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or by phone: +61 3 9699 8822. One-month trials can be arranged on request.

Please click here for more information about institutional subscriptions to Australian Book Review.