Non Fiction

Handbook of Political Party Funding edited by Jonathan Mendilow and Eric Phélippeau

At its best, political science research is empirical, systematic, comparative, and provides cogent and durable explanations – not just descriptions – of political behaviour wherever it is observed. What a pity then that the Handbook of Political Party Funding, for all its strengths in these areas ...

... (read more)Freedom in White and Black: A lost story of the illegal slave trade and its global legacy by Emma Christopher

Because the settlement of Australia by the British proceeded in a certain way, we tend to forget how unusual it was in 1788 to start a colony without slavery. The year 1788 saw the first major manifestation of the abolitionist movement, which had a massive success by 1807 when the Atlantic slave trade was abolished. ...

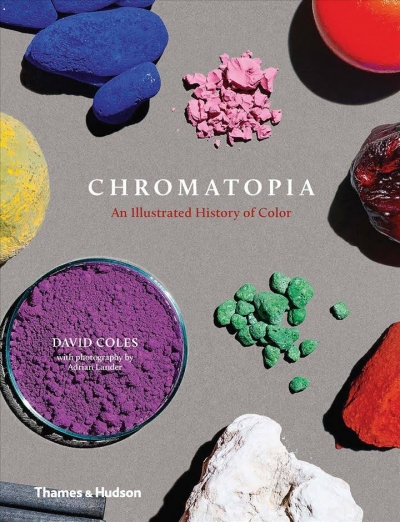

... (read more)Chromatopia: An illustrated history of colour by David Coles

The story of art could be framed as a narrative of tension between the boundless creative imagination of artists and the practical limitations – including instability, scarcity, even toxicity – of their materials. As master paint-maker David Coles explains in this wonderful book ...

... (read more)Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening our eyes by Joanna Mendelssohn et al.

This well-illustrated volume documents through its analysis of art exhibitions the massive rise of Australia’s art gallery attendances over a period of more than forty years. Before the late 1960s, only a few hundred thousand people visited Australian galleries each year ...

... (read more)Performing Hamlet: Actors in the modern age by Jonathan Croall

'It is arguably the most famous play on the planet’, writes Jonathan Croall in his introduction to this absorbing study of how the play and its eponym have gripped the imagination across the ages – and, as far as this book is concerned, particularly across the last seventy years. Whether for actor or director, Hamlet has always been ‘a supreme challenge’, making huge demands on those bringing it to theatrical life.

... (read more)The World Only Spins Forward: The ascent of angels in America edited by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois

Empire of Enchantment: The story of Indian magic by John Zubrzycki

Almost before drawing breath, we meet two troupes of Indian magicians. One appears in the court of the Emperor Jahangir, early seventeenth-century Mughal ruler and aficionado of magic. In the first of twenty-eight tricks, this troupe of seven performers sprout trees from a cluster of plant pots before the emperor’s eyes ...

... (read more)Back from the Brink, 1997–2001: The Howard Government Volume II edited by Tom Frame

Back from the Brink is the second volume of a projected four-volume series that investigates the performance of the four Howard governments (1996–2007). The first dealt with the Liberal– National Party coalition’s election in 1996 and their first year in power. The work under review focuses on the period from ...

... (read more)The Luck of Friendship: The letters of Tennessee Williams and James Laughlin edited by Peggy L. Fox and Thomas Keith

The tall, handsome, socially adept if emotionally reticent scion of a wealthy, well-connected family and the crumpled, physically unimpressive, excitable son of an alcoholic travelling salesman seem to be an unlikely pair to form a long-standing friendship. For both James Laughlin and Thomas Lanier ‘Tennessee’ Williams ...

... (read more)The Environment: A History of the Idea by Paul Warde, Libby Robin, and Sverker Sörlin

On 6 October 2018 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report warning of the dangers of surpassing a 1.5° Celsius rise from pre-industrial levels in average global temperatures. They are many, and dire. To halt at 1.5°, carbon emissions need to fall by forty per cent globally by 2030 ...

... (read more)