Media

Mary Cunnane, who has worked in the publishing industry since 1976, laments the laziness and irritation of those publishers who resent and underestimate unsolicited submissions from authors

... (read more)Killing Fairfax by Pamela Williams & Rupert Murdoch by David McKnight

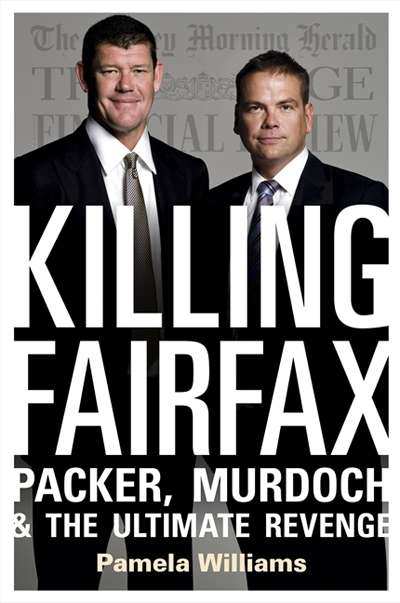

With James Packer and Lachlan Murdoch grinning smugly on its cover, Killing Fairfax: Packer, Murdoch and the Ultimate Revenge projects a strong message that they are indeed the company’s smiling assassins. Pamela Williams mounts a case that these scions of Australia’s traditional media families ...

... (read more)When I was a teenager, I attended a theatre workshop organised by Australian Theatre for Young People. Nick Enright, who led the workshop, told a story about seeing the opening-night production of David Williamson’s The Removalists (1971) from backstage. Twenty years on, Enright’s description of the look on the audience’s faces as they contemplated the ...

The New Front Page: New Media and the Rise of the Audience by Tim Dunlop

Ten years ago, if you moved in certain journalistic circles, calling yourself a blogger was about as popular as leprosy. Few in the industry had respect for the platform, and fewer still would have read your work. Print journalists seemed divided on whether blogging was a joke or a threat. Either way, it was a sure-fire way to end a conversation fast. But the digitisation of the media and its attendant upheaval of the newspaper business model changed everything. The occupational clichés of ink-stained fingers and the printing press were swiftly replaced with scrolling RSS feeds and the ubiquity of smartphones, constantly aglow. Circulation figures – and the dubious methods used to calculate them – were deemed irrelevant. Page views and time-stamps became the new metrics of an article’s (or an author’s) worth.

... (read more)The New Front Page: New Media and the Rise of the Audience by Tim Dunlop

Ten years ago, if you moved in certain journalistic circles, calling yourself a blogger was about as popular as leprosy. Few in the industry had respect for the platform, and fewer still would have read your work. Print journalists seemed divided on whether blogging was a joke or a threat ...

... (read more)When I was a teenager, I attended a theatre workshop organised by Australian Theatre for Young People. Nick Enright, who led the workshop, told a story about seeing the opening-night production of David Williamson’s The Removalists (1971) from backstage. Twenty years on, Enright’s description of the look on the audience’s faces as they contemplated the ...

It is a hot gusty day in the summer of 1958, the sort of day that melts the tar on the road and brings the red dust down from the north. In the inner-city Adelaide suburb of Norwood, Mario Feleppa, twenty-eight and not long arrived in Australia, is fed up. Not with the heat – he is used to heat back in Italy – but with horses. Specifically, the horses that ...

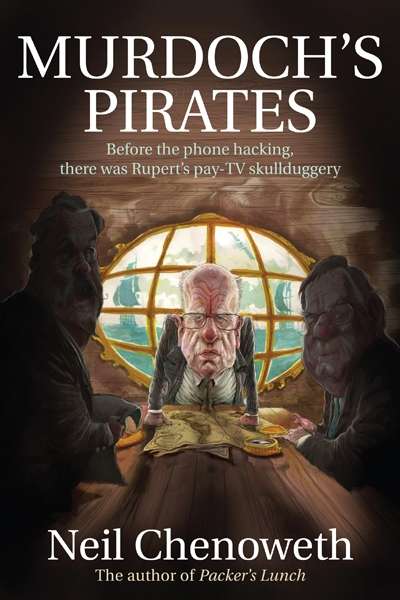

Murdoch’s Pirates: Before the Phone Hacking, There Was Rupert’s Pay-TV Skullduggery by Neil Chenoweth

Talk about unfortunate timing. On 10 December 2012, the New Yorker ran a lengthy profile on Elisabeth Murdoch, the older sister of Lachlan and James. Elisabeth, forty-four, lives in Britain, where – while her siblings have been marked down for everything from, in Lachlan’s case, One.Tel to Ten Network and, in James’s case, MySpace and phone hacking – she has quietly built a reputation as a savvy television producer and businesswoman. The profile is a public relations hosanna – unsurprising given that Elisabeth’s husband, Sigmund Freud’s great-grandson Matthew Freud, is a flack with his own PR firm – with the title declaring its subject to be, in capital letters, THE HEIRESS. The subheading simply states: ‘The rise of Elisabeth Murdoch.’

... (read more)The skills involved in writing successful novels are rather different from those needed for a weekly newspaper column. In a column, a thousand words must engage the reader, week in week out, whether or not the writer has anything urgent to say. A short deadline is less forgiving, allowing scant time for polishing and self-editing. On the other hand, stylistic idiosyncrasies that might become tiresomely repetitive in a longer format can be indulged, even encouraged – part of the charm.

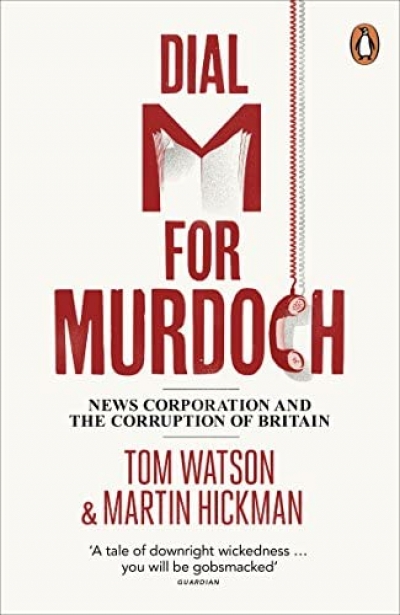

... (read more)Dial M for Murdoch: News Corporation and the Corruption of Britain by Tom Watson and Martin Hickman

It all began with Prince William’s knee. Not, of course, the phone hacking and bribery and corruption which, as we all now know, was commonplace behaviour in the British tabloid newspapers at the heart of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire – that had been going on for far longer. But when, in November 2005, the News of the World carried a trivial story about the prince – ‘Royal Action Man’ – receiving treatment for a strained tendon, he and Prince Charles’s staff realised that this and other leaks could only have come from someone accessing his voicemail. St James’s Palace, fearing a security threat to a future king, called in the Metropolitan Police.

... (read more)