History

In The Year It All Fell Down, journalist Bob Ellis revisits 2011, a year that, as the title suggests, produced social and political change on a global scale. The text provides a month-by-month account of this dramatic time. Ellis covers the Queensland floods and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami ...

... (read more)Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England by Neil McKenna

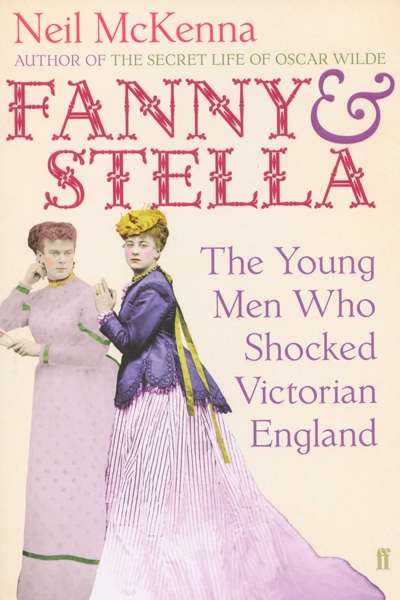

The trial of Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton in 1870 might have been designed for the media to whip up public outrage in a familiar mix of moral disapproval and prurient detail. As Neil McKenna’s Fanny and Stella reveals, this was indeed the intention of the British government of the day.

... (read more)Collecting Ladies: Ferdinand von Mueller and Women Botanical Artists by Penny Olsen

We are used to modern science being conducted as a collaborative effort involving teams of researchers in laboratories, but imagine a huge research project requiring thousands of researchers and covering every corner of an entire continent (and beyond) being organised successfully with no telephone or Internet.

... (read more)Extravagant Inventions: The Princely Furniture of the Roentgens by Wolfram Koeppe

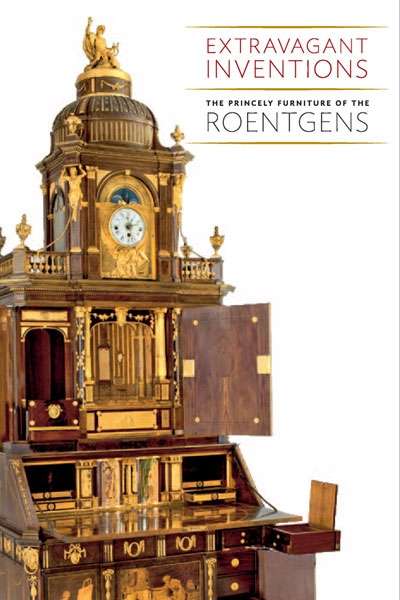

Such was the esteem of the Roentgens – father Abraham and son David – that fourteen years after David’s death in 1807, Goethe, whose father owned Roentgen furniture, knew that his readers would appreciate the metaphor. Probably not since the Great bed of Ware, c.1590 – referred to by Sir Toby Belch and in Ben Jonson’s Epicœne – had furniture such a famous literary champion. The Roentgens were not just ordinary cabinetmakers. Indeed, they were among the most celebrated European furniture makers of the second half of the eighteenth century.

... (read more)Turner from the Tate: The Making of a Master edited by Ian Warrell

Turner posed a conundrum when he withheld nothing from his bequest to the nation. On the positive side, the unsorted contents gave room to later, highly flattering interpretations of Turner, which a collection pruned to the taste of the Victorians would not have supported. On the downside, the digestive processes of posterity took Turner away from his roots in England between 1775 and 1851. In the 1970s, despite much excellent scholarship, English ideas about Turner’s creativity appeared to be as conflicted as ever: the Tate Gallery’s display of the bequest was an unsorted mix, further decontextualised by modern frames and modernist rooms. The following generation of curators, art history-minded, has sought to resolve the conundrum by showing Turner as an actor of his time and place. Accordingly, Tate curator Ian Warrell rummaged around in the bequest for a biographical portrayal of Turner from the Tate the exhibition now showing in Canberra.

... (read more)Perilous Question: The Drama of the Great Reform Bill 1832 by Antonia Fraser

ver fifty years have passed since I wrote my first tutorial essay in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics (PPE), or Modern Greats, as it was known in Oxford. The subject was the Great Reform Bill of 1832, which for the first time in over a century expanded the right to vote and redrew the electoral map of Great Britain ...

... (read more)The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia by Dane Kennedy

Dane Kennedy reminds us that not so long ago exploring held an honoured place among recognised professions. Today, though, the job is extinct. For about a century and a half, the business of exploration was most vigorously pursued in Africa and Australia, yet among the thousands of volumes devoted to ...

... (read more)Taking Stock: The Humanities in Australia edited by Mark Finnane and Ian Donaldson

This is a highly intelligent collection of essays by some of the nation’s finest minds about the ebb and flow of intellectual endeavour in the humanities since the institution of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1969. In the thirty-one essays – built around keynotes, panels, and responses – there are too many gems among them for me to be willing to pick out individual contributions for particular attention. If you care for the life of the mind and for our culture, download the e-book and peruse it, according to your interests. These are mainly stories of success, in transforming disciplines and the like. Less flatteringly, they are also a reminder that the humanities were more central in Australian universities back in 1969 than now.

... (read more)The Love-charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War by Lara Feigel

My mother-in-law often spoke fondly of the Blitz. I had visions of her as a plucky young woman cycling down the bombed streets of London, going to work as a secretary to the stars of show business, enjoying ridiculously cheap hotel meals, and in the evenings going out on the town with an exciting boyfriend – perhaps a Turkish admiral, perhaps the man she later married. It always sounded as if she was having the time of her life. I was puzzled by this, because I knew her parents had both been killed in a bombing raid, though she didn’t talk about that. Was she unconsciously putting a positive spin on a time that must have been distressing and terrifying?

... (read more)Air Disaster Canberra: The plane crash that destroyed a government by Andrew Tink

On 13 August 1940 a Hudson Bomber travelling from Melbourne crashed near Canberra, killing all ten people on board. Three of the deceased were federal ministers: Geoffrey Street (army minister), Sir Henry S. Gullett (vice-president of the Executive Council), and James Fairbairn (minister for air and civil aviation). Also on board that day was Cyril Brudenell Bingham White, a senior Army officer (chief of the general staff).

... (read more)