History

'I Wonder': The life and work of Ken Inglis edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark

I am ashamed to recall that when our high-school history class in the late 1970s was set K.S. Inglis’s The Australian Colonists (1974), I – and I don’t think I was alone – didn’t quite know what to do with a text that focused on ‘ceremonies, monuments and rhetoric’, one that began as a study on 26 January 1788 but worked back as an historical enquiry from 25 April 1915.

... (read more)Fate of a Free People: A radical re-examination of the Tasmanian wars by Henry Reynolds

Making the sea passage south to Flinders Island, I began reading this while off-watch, hoping book and destination might augment, but tough weather cancelled free time until after a landfall sleep. I’ve not much enjoyed histories which cast these manuka and granite islands in dismal role, they are shockingly beautiful, but the crowded cemetery wails, the old lath church is empty of joyful song, and the rule of Commandant Jeanneret recalls similar miseries of bonded Malay and Bantamese on Cocos.

... (read more)It seems hard to imagine that we need more books on World War I after the tsunami of publications released during the recent centenary. Yet, here we have a blockbuster, a 926-page tome, Staring at God, by Simon Heffer, a British journalist turned historian in the tradition of Alistair Horne and Max Hastings.

... (read more)The Great War: Aftermath and commemoration edited by Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves

The centenary of World War I offered a significant opportunity to reflect on the experience and legacy of one of the world’s most devastating conflicts. In Australia such reflection was, on the whole, disappointingly one-dimensional: a four-year nationalistic and sanitised ‘memory orgy’ (to use Joan Beaumont’s wonderful phrase). It did, however, galvanise historians to produce important new studies of the war and to tackle long-standing questions about Australians’ attachment to Anzac. Many of those historians, established and early career, feature in The Great War: Aftermath and commemoration.

... (read more)On Red Earth Walking: The Pilbara Aboriginal strike, Western Australia 1946–1949 by Anne Scrimgeour

It was only seventy years ago that Aboriginal workers in the north-west of Western Australia emerged from virtual slavery on the pastoral stations in the Pilbara region. Through their own efforts, and with encouragement from some white supporters, they radically changed the industry and undermined a colonising process of government control over them. Their protest is known as the 1946–1949 pastoral workers’ strike, which Anne Scrimgeour declares ‘has the quality of a legend’. In On Red Earth Walking she verifies the story. Her meticulous archival research and evidence, from those whose planning and actions were mostly not recorded, lead her to new understandings. It is her relationship with the strikers and their descendants that makes her book unique, for she conveys their response to colonisation through their eyes.

... (read more)Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse by Cassandra Pybus

Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse follows the life of the strong Nuenonne woman who lived through the dramatic upheavals of invasion and dispossession and became known around the world as the so-called ‘last Tasmanian’. But the figure at the heart of this book is George Augustus Robinson, the self-styled missionary and chronicler who was charged with ‘conciliating’ with the Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples. It is primarily through his journals that historians are able to glimpse and piece together the world fractured by European arrival.

... (read more)Who Owns History?: Elgin’s loot and the case for returning plundered treasure by Geoffrey Robertson

After his success in forcing the British Natural History Museum to return skulls and bones of Tasmanian Aboriginals, the human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson was asked by the Greek minister of foreign affairs to ascertain whether international law could be used to induce the British to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece. Although the project found favour with a succession of Greek prime ministers, the Tsipras government decided not to act on Robertson’s recommendations. This book is a revised version of his report, along with a discussion of demands for the repatriation of other cultural treasures.

... (read more)Cold War Exiles and the CIA: Plotting to free Russia by Benjamin Tromly

Ivan Vasilevich Ovchinnikov defected to the Soviet Union in 1958. After three years in West Germany, he had had enough of the West with its hollow promises. He was a farmer’s son, and his family’s property had been confiscated and the family deported as ‘kulaks’ during Stalin’s assault on the Russian village in the early 1930s. Ovchinnikov managed to escape the often deadly exile, obscured his family background, and made a respectable career. Brought up in a children’s home, then trained in a youth army school, the talented youngster eventually entered the élite Military Institute for Foreign Languages in Moscow. In 1955, now an officer and a translator, he was sent to East Berlin as part of the army’s intelligence unit.

... (read more)This Is the ABC: The Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1932–1983 by Ken S. Inglis

The title of Ken Inglis’s book is a poignant irony, reflecting the transience of history itself. For its publication coincided exactly with the death of the Commission, and the birth of the Corporation, and with hindsight one can say that it should have been called That was the ABC, thus creating a pleasant symmetry with That Was the Week That Was. But Inglis did his best to defeat time by bringing the history up to the federal election of 5 March 1983, edging his way as near as possible to the date he would like to have reached.

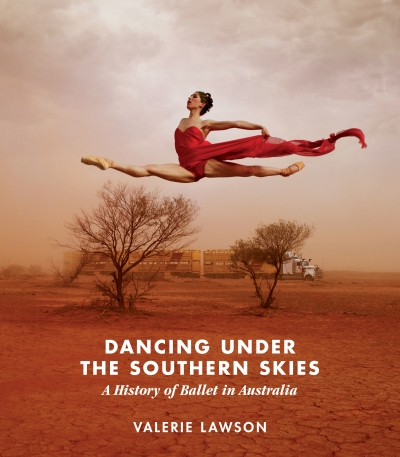

... (read more)Dancing Under the Southern Skies: A history of ballet in Australia by Valerie Lawson

Valerie Lawson is a balletomane whose writing on dance encompasses newspaper articles and also articles and editorials for numerous dance companies. Lawson’s lavishly illustrated Dancing Under the Southern Skies, like Arnold Haskell’s mid-twentieth-century popular histories of ballet, substitutes stories about ballet and ballet dancers for a cohesive historical narrative about ballet in Australia. Portraits, images of ballet dancers posing in photographers’ studios, and ephemera are reproduced in the book; but the total sum of stage photos – of dancing – can be counted on one hand.

... (read more)