Australian History

Michael Gurr was Victorian Premier Steve Bracks’s first senior speechwriter. I am his latest. Gurr worked for Victorian Treasurer John Brumby when he was leader of the state opposition in the mid-1990s. So did I. Gurr wrote the launch speeches for Steve Bracks’s successful 1999 and 2002 state election campaigns. As I type this review, I am also, coincidentally, in the midst of ballpointing my way to the summit of my first draft of the launch speech for the 2006 campaign (a campaign that I cannot know the result of as I type, but you will already know as you read this). The coincidences do not end there.

Gurr’s speech for the 1999 campaign – one made famous by the unexpected defeat of Premier Jeff Kennett – was launched in Ballarat. The 2006 campaign will be launched in Ballarat. Gurr is known in Labor circles as a ‘creative type’ (read: prolific, award-winning playwright of works such as Jerusalem and Sex Diary of an Infidel). I am also known as a ‘creative type’ (novelist and poet). And yet, despite all these coincidences and intersecting lines, not to mention the backbench of associates we have in common, Gurr and I had never met when a speech request landed on my desk a while back with the title ‘Michael Gurr book launch’. Of course, I knew of Gurr. Sort of.

... (read more)Burn: The epic story of bushfire in Australia by Paul Collins

In November 2002 Paul Collins fulfilled ‘that dream of the urban middle class’ and bought a bush block and a shack in the Snowy Mountains ‘where I could be close to the environment’. In late January 2003 his block was scorched by probably the most widespread bushfire since European settlement, and certainly the worst one since the horrific bushfires of 1939. Those two archetypal fires – Black Friday 1939 and the alpine fires of 2002–03 – are the events around which the author has shaped a narrative of bushfire over two hundred years. His strong account of the Canberra fires of 2003 reminds us that they were the outer edge of a massive alpine event.

... (read more)Luca Antara: Passages in search of Australia by Martin Edmond

This novel by New Zealand-born Martin Edmond is difficult to pin down. As I read it, I wondered which genre it belongs to. The narrative moves among various genres, blurring memoir, travelogue, conventional history, reflections upon the internal journeys offered by personal reading, anthropological record, meta-textual fiction as postmodern mystery, even hoax. The unnamed narrator is a professional writer and researcher, thus suggesting an autobiographical element, and his considered reflection on the ‘Ern Malley’ hoax is perhaps the clue to the ‘fiction’ that ultimately engages him; that is, the mysterious document he receives that describes a Portuguese settlement near Darwin in the early seventeenth century.

... (read more)After the phenomenal success of his Gallipoli (2001), Les Carlyon has turned his attention to the experience of Australian soldiers on the western front in the years 1916–18. Carlyon’s purpose in The Great War is clear: he wants to expand the national gaze that is transfixed on the military exploits at Anzac Cove, to include the lesser-known stories of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in France and Flanders. Five times as many Australians perished in the war’s main European theatre as had died fighting at Anzac Cove, but those post-Gallipoli soldiers tend to be accorded a second-rung status in the nation’s memory of the war. As Carlyon says: ‘There were so many, and they were ours, and we never really saw them.’

... (read more)Saving Australia: Curtin’s secret peace with Japan by Bob Wurth

As a middling country far from the centre of major world events, Australia has usually bobbed about in the wake of greater Pacific powers. After being a dependency of Britain for nearly two centuries, the country was accustomed to having its fate decided by distant power brokers. Yet Australian leaders occasionally attempted to strike out on their own in pursuit of what they saw as distinctively Australian interests. Alfred Deakin did it in 1908 when he ignored the usual diplomatic niceties of consulting the British Foreign Office before inviting the American fleet to visit Australia; Billy Hughes did it with his grandstanding at the Versailles peace conference of 1919; and Robert Menzies and John Curtin did it during the desperate days of mid-1941, when they tried to keep Japan out of the war, as British Empire forces struggled to maintain their tenuous hold on the Mediterranean.

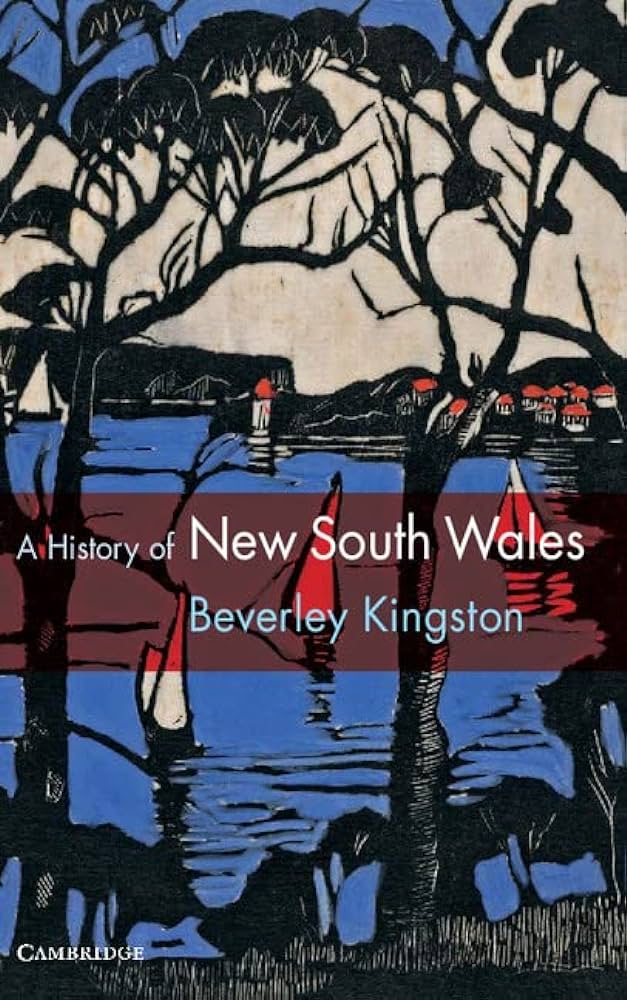

... (read more)This book has one of the most beautiful covers you could hope to see: a Margaret Preston woodcut of Sydney Harbour, in rich blue, scarlet and ivory. Nor does the inside disgrace the exterior. It is a long time since anyone attempted a history of New South Wales, more than a century according to the blurb, presumably a reference to T.A. Coghlan’s annual publication, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales, the last edition of which appeared in 1901. Beverley Kingston is highly qualified to do the job, and the twentieth-century detail is especially good.

... (read more)Francis de Groot: Irish fascist, Australian legend by Andrew Moore

There was a time in Australia when right-wing citizens of this country were passionate and organised enough to bring the left-led state of New South Wales to the brink of civil war on political grounds. This violent opposition was led by rebel elements among ‘as many as 30,000 members’ of a conservative and ‘formally constituted civilian reserve’ known as the Old Guard. Impatient with the staid organisation, they had forged a more militant collective under the guise of the New Guard. One of the major players in this evolution was Captain Francis Edward De Groot, an antique-dealer and reproduction furniture manufacturer from Ireland, whose ambition and taste for adventure had led him to Australia. De Groot went on to star in the most famous scene of this political drama and to carve his name into Australian popular myth by usurping Premier Jack Lang as the ribbon-slasher at the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

... (read more)This book opens in Papeete one evening in 1935. Two American film-makers are in Tahiti to take location shots for Mutiny on the Bounty, and director Frank Lloyd laments his failure to find Captain Bligh’s log books. A small white-haired person of indeterminate appearance at the next table leans over: ‘I know where they are,’ she says. Of course she did. The logbooks were in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and the speaker was Ida Leeson, Mitchell Librarian from 1932 to 1946. The Mitchell Library, located in the Public (now State) Library of New South Wales, is based on the priceless collection of Australiana and south-west Pacific materials donated in 1907 by the reclusive bibliophile David Scott Mitchell. Leeson, its second chief custodian, not only knew the vast collection backwards but added significantly to it. She also used it herself, a key to effective librarianship.

... (read more)What If?: Australian history as it might have been edited by Stuart Macintyre and Sean Scalmer

Thirteen scholars here have fun changing the course of Australian history, but this diverting exercise has the serious purpose of making the real history fresher, more complex and surprising.

Even the more implausible scenarios can have this effect. Marilyn Lake imagines Prime Minister Alfred Deakin declaring independence from Britain in 1908 and aligning Australia with the United States, which brings to our attention the high place in the Australian imagination accorded to the American republic as exemplar, potential ally and partner in the spreading of a vigorous white manhood across the new world. Ann Curthoys ponders the character and influence of feminism by imagining a men’s movement emerging in the 1970s.

... (read more)This is the ABC: The Australian Broadcasting Commission 1932–1983 by Ken Inglis

Ken Inglis is now as much a part of the history of the ABC as any of the charismatic broadcasters, mercurial managers or audiences – devoted and indignant – that his two monumental histories chronicle. He has become the repository, the source, the critical race memory of the ABC, ‘just three years older’ than the phenomenon he examines.

The list of corrigenda at the end of the new edition of This Is the ABC (first published by Melbourne University Press in 1983) underscores the point: insiders, listeners, viewers and politicians have inundated him with corrections and information to refine and expand his already minutely detailed volume one of the history. Listeners plead with him to include the story of the newsreader who announced that a lady had been bitten on the funnel by a finger-webbed spider. Other responses are less benign. Solicitors for Sir Charles Moses, for thirty years the ABC’s general manager, write to Inglis in 1983 listing ‘imputations’ in his book which they claim are grossly defamatory of Sir Charles’s good name and reputation. Sir Charles himself, at the Broadcast House launch of the first volume in 1983, greeted the disconcerted author with the news that he would be hearing from his solicitors. ‘I did my best to look and sound at ease when Dame Leonie called me to the dais’, recalls Inglis. The case was not pursued, and the relevant documents are now deposited in the National Library. But it is characteristic of the man and the historian that Inglis should ‘remain sad that although my admiration for the ABC’s principal maker was evidently clear to reviewers and other readers, the subject himself could not see it’.

... (read more)