Australian History

Black Kettle and Full Moon: Daily life in a vanished Australia by Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Blainey is seventy-three years old and has published thirty-two books. Since his last book was a history of the world, one might have assumed that he had reached the end of his career. But he is not done yet. He moves, as he has always done, from grand speculation to what might be thought trifles – in this case, the details of everyday life in Australia from the 1850s to 1914.

... (read more)The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia by Bill Gammage

This bold book, with its lucid prose and vivid illustrations, will be discussed for years to come. It is not original in the narrow sense of the word, but it takes an important idea to new heights because of the author’s persistence and skill. Bill Gammage, an oldish and experienced historian of rural background ...

... (read more)Into the Unknown: The Tormented Life and Expeditions of Ludwig Leichhardt by John Bailey

In 1848 Ludwig Leichhardt and half a dozen companions set out from Queensland’s Darling Downs, intending to cross the continent to the Swan River Colony in Western Australia. The entire expedition disappeared, virtually without trace. Since then at least fifteen government and private expeditions have tried to ...

... (read more)The Adelaide Park Lands: A Social History by Patricia Sumerling

Novelist Janette Turner Hospital’s recent essay in praise of New York’s Central Park remarked on its visibility from outer space. No doubt Adelaide’s Park Lands, an integral part of the 1837 vision of founding surveyor Colonel William Light’s plan for the city, can also be seen from outer space.

... (read more)Liberty: A History of Civil Liberties in Australia by James Waghorne and Stuart Macintyre

In 1988 the Hawke government put a constitutional amendment to a referendum. On the recommendation of the government’s Constitution Commission, we were invited to vote to enshrine guarantees of trial by jury, property rights, and freedom of religion. The proposition was rejected by all states. There is nothing surprising in that. We almost always do vote against constitutional amendment because the politicians of the right have always succeeded in persuading us that the original document (a free trade agreement between the federating colonies) is perfect and, in any case, any proposal for change is a left-wing plot to deprive her majesty’s loyal subjects of their common law freedoms.

... (read more)Letters to My Daughter: Robert Menzies, Letters, 1955–1975 edited by Heather Henderson

Heather Menzies was ‘the apple of her father’s eye’, reported A.W. Martin, Sir Robert’s authorised biographer, and this collection of letters reveals that she was indeed, to use her father’s own words, ‘the great unalloyed joy of my life’. So much so that Ken, her elder brother, confessed to being jealous of her in his younger days. Heather married Australian diplomat Peter Henderson in 1955 and moved to Jakarta, when these letters begin, but her political education began years beforehand. In a letter that Menzies wrote to Ken (not published here), who was serving in the Australian forces during the war, he proudly describes his sixteen-year-old daughter’s ‘sotto voce comments in the galleries during speeches by such favourites as Forde and Ward and Evatt … [as] worth going a long way to hear’. This extremely close relationship and sharing of political values between father and daughter had an interesting precedent: Dame Pattie had enjoyed a similar bond with her father, the politician and manufacturer John William Leckie. Politics was the stuff of life for the Menzies family, both in Opposition and government. Heather accompanied her parents on official engagements that included overseas trips to India in 1951 and London in 1952, and travelled with them on the hustings during electoral campaigns.

... (read more)This year is the 175th anniversary of European settlement in South Australia. The University of Adelaide presented a series of public lectures collectively called Turning Points in South Australian History. Bill Gammage gave the first and showed by an accretion of primary sources that, prior to white settlement in 1836, Aborigines kept a tidy landscape thanks to the controlled use of fire. First Adelaidians exclaimed that the landscape was close to an English garden. Henry Reynolds gave the second lecture, and made much of the political and social timing of the settlement, after the abolition of slavery in London and just before the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand. The idea of terra nullius was in its preliminary colonial tatters.

... (read more)The Paper War: Morality, Print Culture, and Power in Colonial New South Wales by Anna Johnston

‘A MISSIONARY ARRESTED! A LONDON MISSIONARY ARRESTED!!’ These alarming words were trumpeted in the Sydney Gazette in 1828, and they shout from the back cover of Anna Johnston’s The Paper War. Readers might be forgiven for assuming that this book is about scandals in early colonial Australia – all the more entertaining for involving clergymen. And in a way it is, for the man arrested, Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, is the book’s central character. His endless battles with his peers and superiors via the printed, written, and spoken word are a major focus of this book.

... (read more)Modern travellers can hardly conceive the perils of the sea in the age of sail. Merchant seamen excepted, today’s average seafarer rides a massive cruise ship warned by radar to skirt round storms and stabilised against the rolling of all but the most powerful swells. The terrors of the deep do not extend far beyond poor maintenance, food poisoning, bad company, and illicit drugs administered by persons of interest to the police. Global positioning devices make navigation a breeze. Fifteen-year-old girls single-handedly circumnavigate the globe, and Antarctica is a fun destination for seniors.

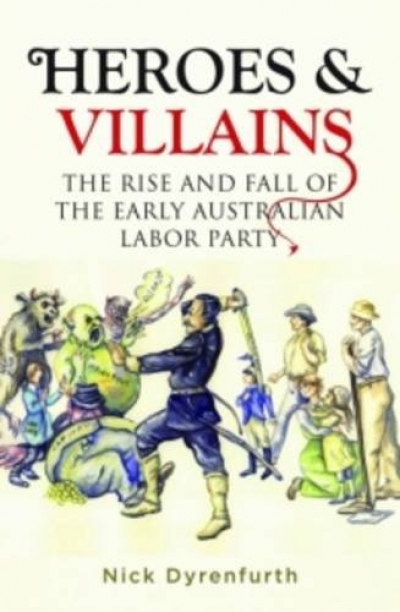

... (read more)Heroes & Villains by Nick Dyrenfurth & A Little History of the Australian Labor Party by Nick Dyrenfurth and Frank Bongiorno

The heroes and villains in Nick Dyrenfurth’s account of the early Labor Party are the cartoon figures in the labour press that he uses to explore its political rhetoric. The heroes are sturdy working men, sometimes in bush garb, sometimes industrial labourers. The villains take various forms: serpents, harpies, bloodsucking insects, menacing aliens, but above all the Fat Man, the swollen, grotesque embodiment of capitalist greed. Dyrenfurth observes that Mr Fat is a far more ubiquitous device in Australian radical iconography than its counterparts elsewhere. British cartoons used a variety of villains: aristocratic loafers, rapacious landlords, ruthless sweaters, mendacious press barons. Those in the United States were less likely to personify capitalism with a generic capitalist villain than to depict combines and trusts.

... (read more)