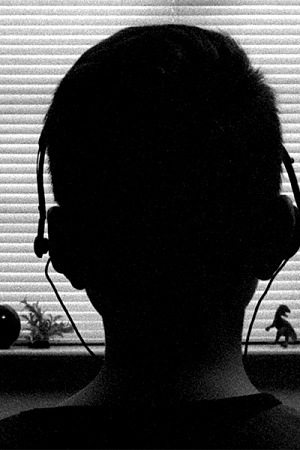

Silence ★★★★1/2

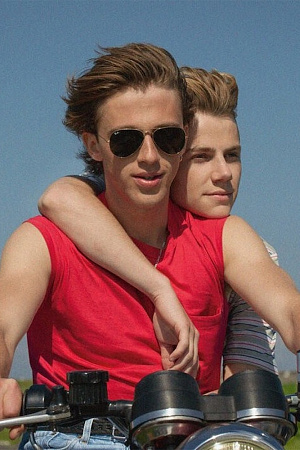

Unlike Martin Scorsese’s previous forays into the subject of spiritual faith, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and Kundun (1997) – both of which used intense, almost delirious musical compositions to evoke a sense of religious fervour – his new film has no score at all. An adaptation of Shūsaku Endō’s 1966 novel Silence, it opens on the intensifying sounds of nature, the buzzing of gnats or crickets, abruptly cut off by a hefty silence. Or is it the silence of the void? This question haunts the two Portuguese Jesuit priests, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver), who have been sent to mid-seventeenth-century Japan to stoke the dying embers of a Christianity under merciless attack by local authorities.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.