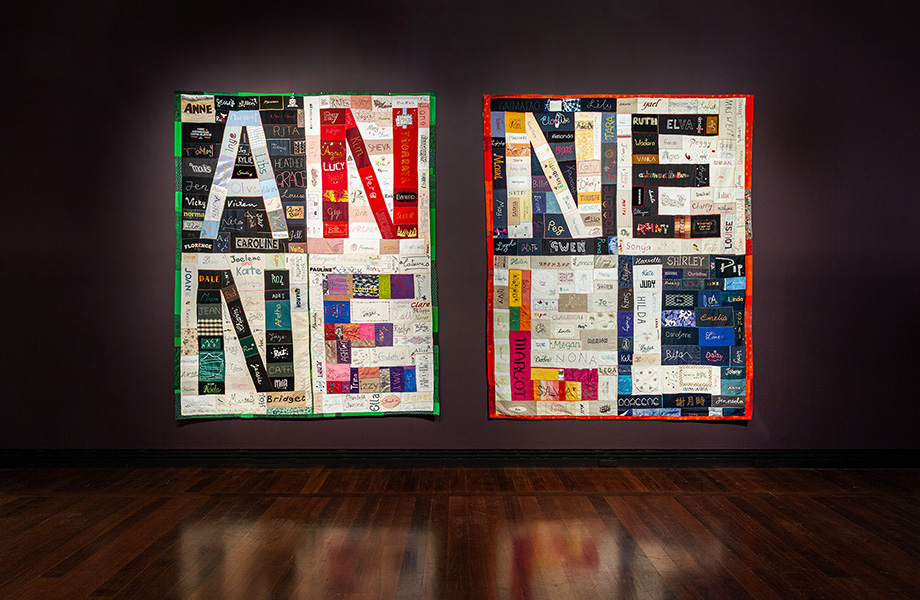

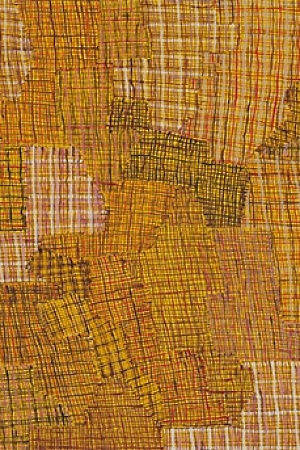

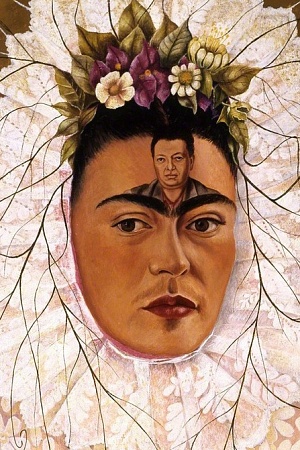

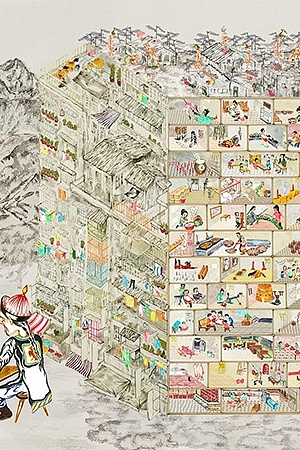

Radical Textiles

Radical Textiles, the home-grown summer blockbuster at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA until 30 March 2025) is ebullient, celebratory, rewarding and responds to a rapidly growing interest: over the past two decades, textiles as an artistic medium, and textile practices as forms of cultural expression, have become increasingly important in contemporary art museums and exhibitions, part of an explosion of artistic media that speaks to women’s lives and work, and to subcultural energies. In short, this show is timely.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.