Biography

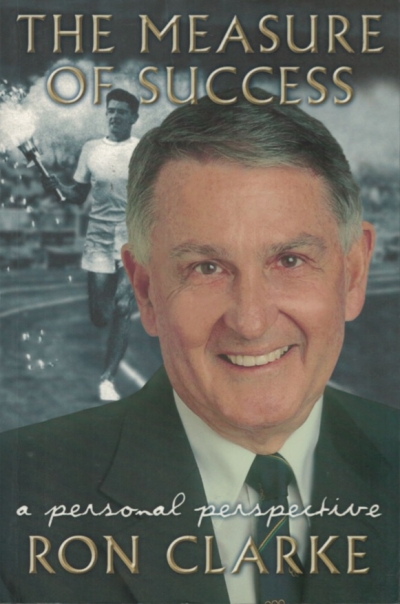

The Measure of Success by Ron Clarke & Cathy by Cathy Freeman (with Scott Gullan)

by Bill Murray •

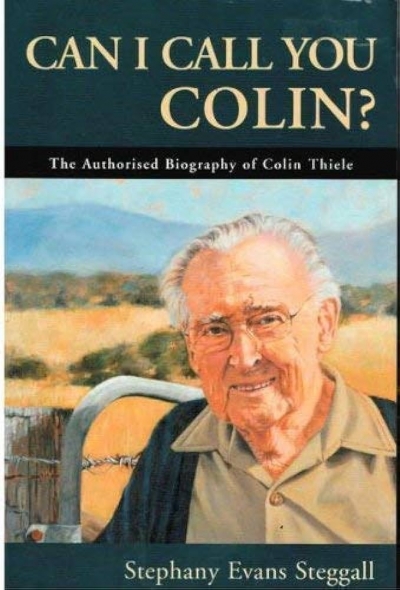

Can I Call You Colin?: The Authorised Biography of Colin Thiele by Stephany Evans Steggall

by Margaret Robson Kett •

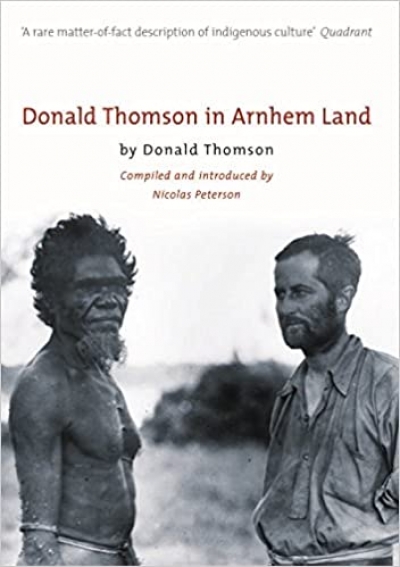

Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land by Donald Thomson, edited by Nicolas Peterson

by John Mulvaney •

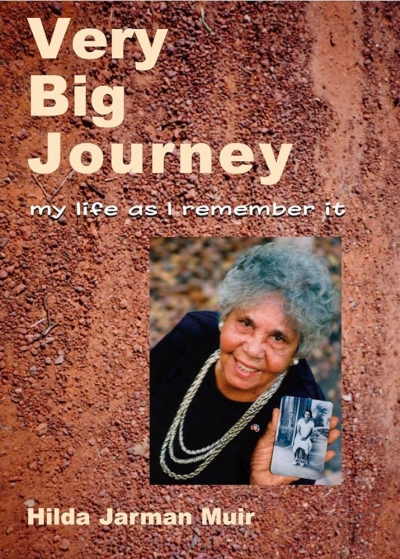

Very Big Journey: My life as I remember it by Hilda Jarman Muir

by Ceridwen Spark •

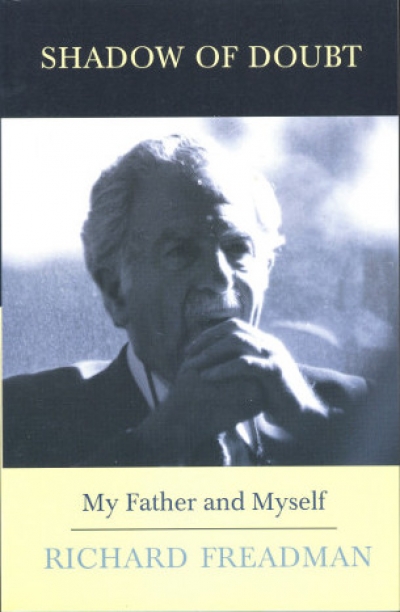

Shadow of Doubt: My Father and Myself by Richard Freadman

by Peter Rose •

George Orwell, born in 1903, was the child of a British Empire civil service family with long Burmese connections, which belonged, as he put it with characteristic precision and drollery, to the lower upper middle class. By the time he went to fight against fascism in Spain in 1936, he had already quit his job in the Burmese colonial police, attempted to drop out of the English class system, and become a writer and a socialist of a notably independent, indeed idiosyncratic, kind.

... (read more)