After Bondi

As the January-February issue of Australian Book Review went to print, a horrifying event was unfolding: the largest terrorist attack on Australian soil and one unambiguously targeting Jews who were celebrating Hanukkah at ‘Chanukah by the Sea’, on Bondi Beach. There is time for examining the deep-seated, long-standing, global factors which led to this – as well as, perhaps, the human-scale, emotional, even banal ones – but, at ABR, we decided now is a time for personal reflection, listening, and grace, as Waleed Aly recently put it. ‘Grace doesn’t ask whether someone is worthy of empathy. It doesn’t treat a cry from the heart first and foremost as though it is simply a political strategy.’ We asked five Jewish Australians to reflect on a simple question, with an inevitably complex answer: ‘After Bondi, how do you feel and why?’ We thank them for their generosity of spirit in taking the time, at this awful time, to find the words. May there be more grace in 2026.

This article was published online on 31 January 2025.

Ilana Snyder

Many people in the Australian Jewish community are angry. The senseless murder of fifteen people, most of them Jews, and the serious wounding of dozens more on the first evening of Hanukkah, is not only the worst terrorist attack in Australia’s history; it is the deadliest assault on a Jewish community in the diaspora this century. The massacre on December 14 at Bondi Beach, yet another date and site to be seared into Jewish memory, has also provoked fear. Anger and fear, mixed with shock and disbelief, have rocked Australian Jews.

There are only 120,000 Jews in Australia – that is less than half of one per cent of the population. Since 9/11, every Jewish kindergarten, primary school, high school, synagogue, library, community centre, and museum has had guards. Since October 7, these guards have carried guns and their presence has been supplemented by security cameras, blast-proof glass, anti-ramming fences, bollards, and double gates. I encounter such security measures each time I pick up my grandchildren from Bialik College. At a cultural event in the Jewish community, my bag is checked. When I participate in community meetings, the location is revealed just hours before it begins. Such precautions have become normalised.

Australian Jews have been aware of the frightening escalation of anti-Semitism since October 7. Before Israel had even reacted to the horrific murder of more than 1,200 people and the abduction of 254 hostages to Gaza, crowds gathered at the Opera House shouting ‘Fuck the Jews’ and ‘Where are the Jews?’, if not ‘Gas the Jews’. It was the first of an increasing number of dreadful, anti-Semitic incidents over the past two years. Jewish schools and synagogues have been firebombed and desecrated with swastikas, vehicles have been set on fire, Jewish creatives have been doxxed, Jewish businesses have been boycotted, hateful graffiti has been sprayed on homes and schools, and neo-Nazis have marched through the centre of Sydney and Melbourne. Now, to be a Jew in Australia is to think twice before gathering for a community event.

My fourteen-year-old grandson tells me that he would never wear a visible Star of David after experiencing an anti-Semitic tirade while handing out how-to-vote cards in support of the Voice. In his rush to get to the polling place after a friend’s bar mitzvah, he had forgotten to remove his kippah. Lost that day was his sense of safety and freedom to express his Jewish heritage in public.

Efforts to explain and contextualise what happened at Bondi have begun. It is about Benjamin Netanyahu and his unprecedented, extremist government. It is about the war in Gaza, where Israel’s response to October 7 was cruel and disproportionate, compounded by constant images of the destruction and misery in the media. It is about Australia’s lax immigration laws. It is about Australia’s failure to tighten gun laws. It is about Australia’s negligence in quelling hate speech in the guise of scripture and theology.

However, for the first time in my life, I am finding it difficult to explain and contextualise the Bondi massacre. The two gunmen were motivated to murder complete strangers simply because they were Jews. Sadly, their heinous act was not something new. Jews have been the victims of anti-Semitism for thousands of years, and I am coming to think that perhaps they always will be.

Until October 7, I found it easy to distinguish between criticism of Israel’s increasingly illiberal government and anti-Semitism. Under Netanyahu, Israel has been in a ‘democracy recession’, as Larry Diamond puts it, sliding towards authoritarianism. Despite my despair at the power of the worst leader in Jewish history, I was buoyed by the strong resistance to his rule within the country. From the beginning of 2023, every Saturday evening, hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens went into the streets to protest.

When those on the left condemned the continuing occupation and the unequal status of the Palestinian citizens of Israel, I did not regard them as anti-Semitic. I agreed with them.

Then came October 7 and, two years later, December 14. Now the boundaries between such critiques of Israel and anti-Semitism have become less clear to me. I am no longer confident about where to draw the line on legitimate criticism of the Israeli government and anti-Semitism. There are those on both the far left and the fascist right who have displayed a deep hatred for Jews. It cannot be ignored.

Australian Jews are calling on the government to stamp out anti-Semitism. Many are demanding the immediate implementation of Australian Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism Jillian Segal’s somewhat dubious recommendations, including the punishment of universities and cultural institutions that have not done enough to control anti-Semitism. But even if her list of actions had been adopted, the Bondi attack would still have happened.

Like all Australians, I took solace in the heroism of Ahmed al-Ahmed, the passerby who tackled the older gunman, wresting his hunting rifle from him. In an act of extraordinary courage, he saved lives. And his wasn’t the only act of bravery. I was also comforted by the images of lifesavers and paddle-boarders at Bondi acknowledging the horror of the massacre in its aftermath. We must build on these gracious acts by returning to the serious work of education. Understanding how our collective safety is threatened by division, violence, and hatred of any kind, including anti-Semitism, is vital. We must work towards community harmony, tempered by respect for the freedom to express our differences. Such action may not eradicate anti-Semitism, but at least its impact will be curbed.

Ilana Snyder is an Emeritus Professor at Monash University, a former Chair of the New Israel Fund (NIF) Australia, and a member of the NIF International Board.

Robert Manne

Following news of the Bondi massacre of fifteen Jews, my wife, Anne, and I barely slept. The depth of the tragedy for all the families is unbearable; the optimistic face of the young girl, named Matilda for the promise offered by Australia, is haunting; the implications for our politics, unpredictable and immense. Before the Hamas murder of 1,200 Israeli Jews on October 7, Australia was possibly the country least affected by the scourge of anti-Semitism. No longer.

The father and son who perpetrated the Bondi massacre were followers of ISIS, an Islamist movement that commands its followers across the globe to murder all Jews and Christians. We do not yet know when the Bondi murderers began to follow ISIS. The son had been of interest to ASIO some years earlier. We do not yet know why there was no red flag when father and son holidayed in Mindanao, the Philippines’ ISIS territory.

It is almost a law of Australian politics that following a loss of lives – in a bushfire, a mine collapse, a shooting spree – the political weaponisation of the tragedy is forbidden for a decent interval. In the case of Bondi, weaponisation occurred almost instantly, with the creation of an alliance of the Coalition, the Murdoch media, and the most powerful parts of the Israel/Jewish lobby. The alliance claimed that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had the power to combat anti-Semitism in Australia after October 7, but he had done almost nothing.

For reasons we cannot yet understand, the government has refused thus far to convene a Commonwealth Government Royal Commission. This suggests to almost everyone that there are some things it wants to hide.

Following Bondi, the Netanyahu government claimed that there was a connection between the massacre and the Albanese government’s recognition of the State of Palestine. Such recognition rewarded Hamas for the murders on October 7, according to Benjamin Netanyahu. Albanese replied that his government was only doing what many Western governments had already done. To prove his support for Israel, he invited the president of Israel to visit Australia. President Isaac Herzog is the head of state but also an active Israeli politician, one who famously blamed the entire Gazan population for the October 7 murders, a statement that will feature in all forthcoming genocide trials. Massive demonstrations can be anticipated if Herzog visits Sydney or Melbourne.

For six months, the government had been sitting on the radical report into anti-Semitism written by Australian Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism Jillian Segal. Following Bondi, Albanese agreed to all her suggestions. Segal calls for unprecedented interventions into the ABC and Australia’s universities. She outlines certain kinds of protests that must be forbidden, certain common criticisms of Israel and Zionism that are inadmissible because they are anti-Semitic. If these institutions fail her tests, they will lose part of their funding.

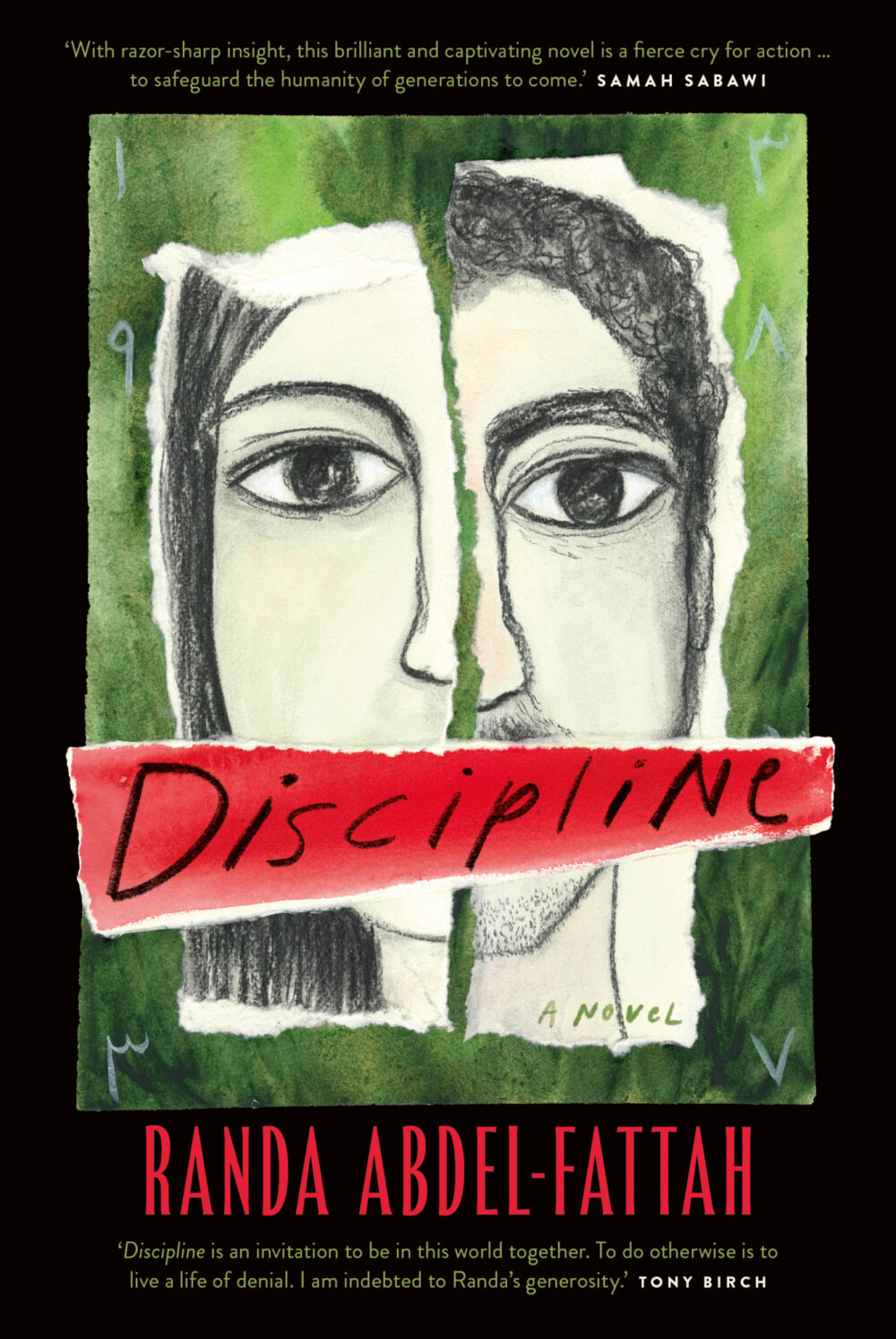

We know what kinds of discussions will be censored. One part of the Israel/Jewish lobby managed to remove Antoinette Lattouf from ABC Sydney radio because of a re-tweet about Israel’s weaponisation of starvation in Gaza. Another part caused Randa Abdel-Fattah, the author of Discipline (2025), an outstanding novel concerning Muslim political intellectuals, to leave the Bendigo Writers’ Festival. A walkout of fifty speakers followed. There have been very many similarly successful interventions.

Such interventions are part of a strange atmosphere of strictly enforced unreality that has accompanied the sharp rise in anti-Semitic acts since October 7 – insults, tweets, graffiti, arson, but no physical violence before Bondi. These acts did not occur suddenly, or for no reason. They are self-evidently connected in ways we must try to understand, in open, non-censorious discussion of Israel’s war in Gaza.

For some two years, Israel has been responsible for the deaths of an estimated 100,000 Gazan Palestinians, mostly innocent civilians, of whom at least 20,000 are children. Israel’s forces have destroyed hospitals, universities and schools, and an estimated eighty per cent of Gazan buildings. Body parts lie strewn under the billions of tons of rubble. Gazans have faced daily fear of death by bombing while they scramble without dignity for food or shelter in scraps of tents without protection from heat or cold or rain. Australians were profoundly shocked by the murder of fifteen people at Bondi. Before the recent ceasefire, there was not a single day when as few as fifteen innocent people were killed in Gaza by Israeli force of arms.

And yet none of this can even be mentioned when discussion turns to the reasons for the growth of an ugly and dangerous anti-Semitic current on the fringes of the massive pro-Palestinian movement in Australia, as seen in the 200,000 Sydney Harbour Bridge marchers. It especially cannot be mentioned when attention turns to Islamist terrorism and the existence in Australia of followers of ISIS, the most murderous movement in contemporary Islam.

I do not write any of this with calmness. I was born to Jewish refugee parents three years after the Holocaust. My writing and teaching have been devoted to the call to action of my generation: ‘Never Again’. Watching Israel’s pitiless destruction of Gaza, we have all learned that for both a large part of Israeli society and the Jewish diaspora, the call to action is the morally and perhaps politically catastrophic ‘Never Again, To Us’.

Robert Manne AO, FASSA, is an Emeritus Professor of Politics at La Trobe University. He is the author of The Mind of the Islamic State (Black Inc. and Prometheus Books). A longer version of this comment will be published on his Substack, Thermidor: Cultural Counter-Revolution in the Age of Trump.

Simon Tedeschi

When I think of Bondi the first thing that comes into my mind is my maternal grandmother, five feet tall with a scowl on her face and beady eyes. The L82 bus would pass Campbell Parade and shortly afterwards reach Dover Heights, where she would be waiting on her balcony like a little lieutenant, disappointed at how late I invariably was because the food she had made had gone colt. As the shots blasted over innocent beachgoers and cut down Australians whose only crime was to be unapologetically Jewish, I felt relief that she was not alive to witness this. She had come to Australia because it was further away from Europe than Canada or the United States, and it was in Europe that her entire family were gassed: brother, sisters, mother, father, cousins, nephews, uncles, aunts. Australia was distance, refuge, and chance – a line drawn in the sand, across the world. Bondi, for her, was not just a suburb; it was proof that survival could take the form of ordinary life: saucepans, sewing machines, bridge sessions. It was in Bondi that she became an ozzi.

The second thing I feel is anger. Anger at the warnings that were repeated and minimised or ignored. Anger at the way social media has turned suffering into a spectator sport, and at the way some people – once they step into that arena – stop being people at all and become performers of themselves. Anger at hatred rebranded as virtue. Anger that Jews must fight to be seen not as proxies of a distant regime but as Australians, citizens grieving their dead; and that this inversion forces them to explain and contextualise their pain before they are permitted to express it. Anger at news sites for weaponising historical language and then wondering why people were killed with weapons. Anger at those who, while accusing Jews of conflation, nevertheless conflate Jews with Israel – and use that contradiction to justify distance from Jewish grief.

Anger at the terrorists, two men whose righteousness hardened into hatred. Sadness that the massacre was avertable. Sadness that many of the politicians I admire should have done more. Sadness that some people on the cultural left – some of them my friends and colleagues – still consider violence against Jews as the last form able of violence able to be contextualised, minimised, and sanitised; where empathy must first be earned through declarations and denunciations.

Sadness at the double standard so deeply internalised that it is no longer seen as one but as a vector for virtue; sadness at the civic fracture that allows it to pass unnoticed. Sadness at imaginative failure, at moral flattening, at ethical conformity: at the refusal to allow Jewish grief to register as human grief – messy, unqualified, unperformed. Sadness that loyalty to one’s ‘team’ often trumps everything. Sadness at the quiet, respectable people who refuse to confront extremism among their own for fear of social or professional exile. Anger that ordinary people are dead, and that even this becomes material for ‘content’.

But I also feel pride. Because we Jews, we Australians, we ozzis, are not going anywhere. Pride in endurance rather than defiance; in the stubborn ordinariness of continuance. Pride in Ahmed al-Ahmed, Boris and Sofia Gurman, Reuven Morrison, and Chaya Mushka Dadon. Pride that we answer with essays rather than denunciations, write poems rather than declare positions. Pride that we now have the opportunity to respond to hatred with humour and with the quiet joy of work. The task of resistance is not to compete in spectacle, but to let banality reveal its own poverty – and art is still the force most capable of this. It will not save our bodies, but it can harden our attention; a discipline, a refusal to let meaning be extinguished along with the body.

The fifth feeling is reconnection. Not tribalism, not the fantasy that any one group is better or worse than any other, and certainly not the corrosive idea that Jewishness confers nobility (it doesn’t), but a recognition that this complicated, unruly family of ours will continue to renew and rebuild, as we did after Babylon, after Rome, after the expulsions and pogroms of Europe, after the Shoah, and after the exiles and persecutions of the Middle East and North Africa. What feels different now is not unity, but clarity: the illusions have thinned, and the work ahead is no longer abstract. And the most important of that work is done hand-in-hand with non-Jews, with Australians of every background, who refuse to mistake extremism for conscience, who understand that solidarity is not contingent on total agreement, and who recognise that there is no viable future here except together.

Bondi is now part of that story – not as symbol, not as parable, but as a place where people lived, loved, swam, and died. My grandmother would not have understood the hashtags or influencers. But she would have recognised the fear, and she would have recognised the resolve. She was a deeply flawed woman, but I suspect she would have said what so many Jews have always said, after every catastrophe and every warning that went unheeded: we grieve, we endure, we remain.

Simon Tedeschi is a classical musician and writer based in Sydney. In 2022, Simon won the ABR Calibre Essay Prize for his essay ‘This Woman My Grandmother’ and he is the author of Fugitive (Upwell, 2022). When neither writing nor practising piano, he reads books and drinks coffee.

Lee Kofman

The morning after the Bondi terror attack, I was scheduled to appear on a podcast about creativity. Going ahead with it was my way of finding that mythical oil jar which, according to Hanukkah lore, lit the Jewish people’s darkness in their hour of need.

My darkness deepened as I drove to the studio. A phone call with a friend turned into a shattering revelation. Her niece, the same age as my ten-year-old child, was murdered in Bondi. The tragedy that sat heavy in me turned visceral. Still, I drove on. I needed to be around good people. To believe in goodness.

My podcast interlocutor, another Jewish artist, seemed similarly shellshocked. ‘I always look for a silver lining’, he said. ‘I haven’t found it yet, but I’m waiting.’ ‘Maybe there won’t be silver lining’, I said. The miraculous oil jar was fiction after all ... We agreed to disagree, as Jews often do, ending the recording with a silent, long hug.

If only I could be so hopeful. In the days since Bondi, I have mostly felt fury and sadness. For two years, since 7 October 2023, my community has been warning that unchecked Jew-hatred – online, in weekly rallies, in cultural institutions, via the boycotting of Jewish artists, the abuse of Jewish university students and lecturers, and anti-Semitic violence – would lead to bloodshed. We had been proven right. It took fifteen dead bodies for people to see what ‘Globalise the Intifada’ looks like in practice. Fifteen dead for Jewish grief and fear to finally receive public validation.

Validation was coming my way too, at first primarily from people who have supported me throughout the last two years, often at their own peril. I received dozens and dozens of moving messages of love and anguish. Was this my silver lining?

Soon others arrived. Still from within my milieu – mostly left wing, creative, non-Jewish people – but now also from those I hadn’t heard from in a long time. And from those who have contributed to normalising Jew-hatred. In certain circles, I realised, validation came with caveats. It felt as if our mourning became a subject of scrutiny, a suspect thing. Some offered condolences then detailed the evils of Benjamin Netanyahu or guns, as if either explained (justified?) what happened. Others, more diplomatic, sent links to videos and articles by those they regard as ‘Good Jews’ – a handful of extreme left, anti-Zionist Jewish public figures and organisations with marginal Jewish followings, whose narratives fit those of some ‘progressive’ milieus and are used by them as shields against accusations of anti-Semitism.

(Bad) Jewish community is overreacting again, Good Jews were saying. Anti-Semitism is as much a problem as other types of racism. Worse, (Bad) Jews are politicising the tragedy to curtail freedoms. Because the rallies with Islamist flags, promoting totalitarian political ideologies, and with chants of ‘all Zionists are terrorists’ were peaceful and must continue. The government has done all it could; look how much money has been poured into security. Jewish organisations should hire more guards and stop celebrating events in the open, then all will be fine. Also, we should tone down our grief, to avoid encouraging Islamophobia, Good Jews suggested.

For those who sent me those later messages, I realised, my grief was conditional. To be entitled to it, I had to pass a moral test: Was I a Good or Bad Jew?

Doubtlessly, I am a Bad one. A Jew who, while opposing the current Israeli government, is deeply connected to my ancestral land, where I lived for fourteen years, and to my community in Australia. A Jew unprepared to dilute her grief for somebody else’s sensibilities. A Jew holding the government and many of our cultural institutions accountable for the marginalisation, hatred, and violence my people have been enduring in this country over the last two years.

Another message came through. A young journalist sent an Instagram reel in which she spoke about deciding to stop minimising her Jewishness to fit in. Normally a gentle person, her words were bold, her fury palpable. I watched the video several times. I could see she was becoming Bad Jew. A badass Jew.

Soon, Bad Jews sprang up all over the place. Many who had been (understandably) fearful and quiet spoke publicly for the first time. The usually outspoken ones took things up a notch. I messaged my podcast interlocutor: ‘You were right. Even Bondi’s tragedy has a silver lining.’ The chorus of my people was growing. The Bad Jews had spoken.

Jews are a mere 0.4 per cent of Australia’s population, not all that useful for vote-courting politicians. Unfortunately, we do not possess those powerful, all-reaching tentacles attributed to us. But we’ve always been a people of words, and our hope to survive is embedded in our willingness to use words boldly and authentically.

In recent years, Bad Jews have been pushed out of many public spheres, told it isn’t the time for our voices. (I was told this many times, especially after the publication of Ruptured: Jewish women in Australia reflect on life post-October 7, which I co-edited with Tamar Paluch.) Since the Bondi massacre, however, the media has been more willing to give space to Bad Jews too.

Today I choose to be hopeful. I notice that while some non-Jews put my grief to test, more have asked how they can help. One important thing to do right now is to listen to Jewish voices, and to choose carefully who you learn from and who you amplify. To show true solidarity is to climb out of your comfort zone and algorithms. To listen to those Jews who challenge rather than confirm what you think you know about us. (Are Zionists really terrorists? Are Jews really white?) After years of the Australian Jewish community being misunderstood and gaslit, light must be shed on our complexities and nuances. Let this be everyone’s silver lining.

Lee Kofman is the author and editor of nine books, including Imperfect (2019), which was shortlisted for Nib Literary Award 2019, and Split (2019), which was longlisted for ABIA 2020. Her latest books are The Writer Laid Bare (2022) and Ruptured (2025). She teaches and mentors writers. More at http://www.leekofman.com.au/

Dennis Altman

After the Hamas attack of October 2023, President Joe Biden warned Israel against overreacting: ‘We must seek justice. However, I would advise you not to let your anger control you while you are feeling it. In the US, we were furious following 9/11. Even though we pursued and received justice, we weren’t perfect.’

We should remember those words in the aftermath of Bondi. Yes, there are real questions to be asked about the failures of our security agencies, both in their latitude towards hate speech and their failure to track the killers, even after concerns had been flagged about one of the men. I wonder whether Premier Chris Minns’ enthusiasm for draconian new laws reflects guilt for failing to have a larger police presence at what should have been seen as a high-risk gathering.

But to link the work of two ISIS-inspired assassins to Palestinian demonstrations is overreach. Yes, anti-Semitism is real and too often has been ignored. Globally, it has resurfaced in frightening ways over the past few years, often in tandem with other forms of racism.

When politicians try to blame its rise on migration they overlook the emergence of neo-Nazi groups, whose supporters are overwhelmingly white and Anglo. Their hatred of Jews is only matched by their hatred of Muslims. It is also true that there are elements of anti-Semitism among some of the most ardent pro-Palestinian activists, again most often Anglos rather than Muslims.

When the Murdoch press is more affronted by actors wearing a keffiyeh during a Sydney Theatre Company curtain call than they are by Nazis marching in the streets, I feel scared. Even Australian Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism Jillian Segal has been slow to call out neo-Nazi protests.

It is essential to recognise that anti-Semitism and opposition to Israel are quite separate issues, even if there are times when all Jews get depicted as Zionists. For Jews like me, who see Israel as a foreign country, this is hurtful. I have long felt that the phrase ‘next year in Jerusalem’, part of the traditional Passover Seder, is deeply hypocritical when I have the right to citizenship in Israel, a right denied to millions of Palestinians.

The Israeli government and mainstream Jewish organisations deliberately blur this distinction. The reason many of us oppose the working definition of anti-Semitism given by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is that it deliberately links anti-Semitism to a defence of Israel, forbidding claims, for example, ‘that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavour’.

It is ironic that the Australian government endorses this, when similar claims about Australia are common among the left. The IHRA definition prevents discussion of the reality that Israel occupies territories where there is no pretence that Palestinians enjoy equal rights with Jewish settlers, despite Israel’s claims that it is the only democratic country in the Middle East.

To call Israel a democracy ignores not just the seven million Palestinians who live under de facto Israeli occupation but also Israeli Arabs, whose legal status is limited by the Nation-State Law of 2018. It would be more accurate to define Israel as an ethno-nationalist state, rather like Narendra Modi’s India.

The constant talk of the need for social cohesion is too often deployed as a weapon against pro-Palestinian rallies. Just imagine how powerful that message could be if the Antisemitism Envoy and the Zionist organisations reached out to the Muslim community and acknowledged the pain they feel viewing nightly carnage in Gaza and settler violence on the West Bank.

That Benjamin Netanyahu used the Bondi tragedy to blame Australia for recognising a Palestinian state (along with most other Western countries) is not only absurd; it also serves to further drive us apart.

But the personal vituperation against Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Minister Penny Wong is appalling (the Governor-General has apparently been urged to dismiss Albanese, in effect to mount a coup, which she is clearly not going to do). I felt Albanese had responded with some dignity, but my faith in him was lost when he invited the Israeli president to Australia, thus reinforcing the narrative that opposition to anti-Semitism and support for Israel are intertwined.

The massacre at Bondi has traumatised an already traumatised community, reaching even those of us who are totally secular and resist identification with Israel. I wrote the introduction and conclusion to my essay collection, Righting My World, in the aftermath of October 2023. Looking back, I realise that they mark the moment when I felt more vulnerable as a Jew than as a gay man.

Dennis Altman is a Vice Chancellor’s Fellow at La Trobe University. His most recent books are God Save the Queen (Scribe, 2021), Death in the Sauna (Clouds of Magellan, 2023), and Righting My World: Essays from the past half-century (Monash University Publishing, 2025).

This is one of a series of ABR articles being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.