Review

Australian Republicanism: A reader by Mark McKenna and Wayne Hudson

by Guy Rundle •

Stromlo: An Australian observatory by Tom Frame and Don Faulkner

by Robyn Williams •

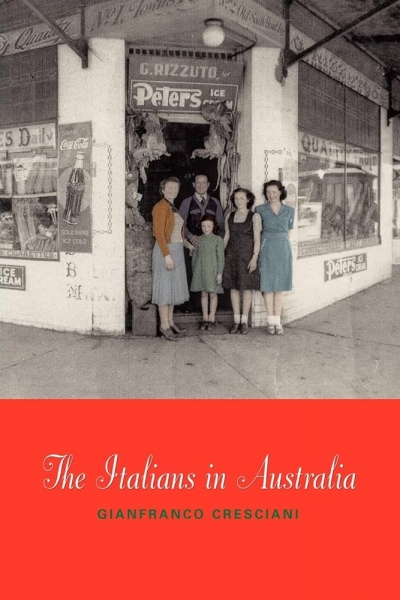

The Italians in Australia by Gianfranco Cresciani

by Loretta Baldassar •

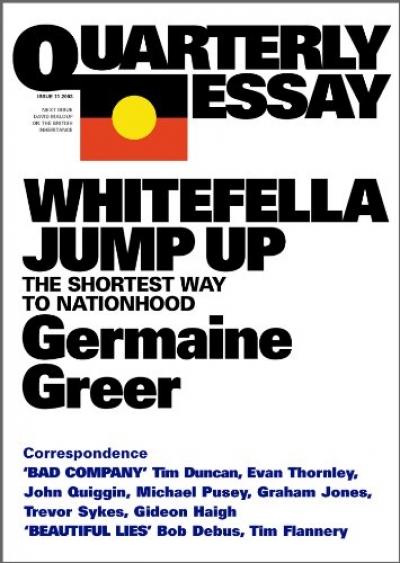

Whitefella Jump Up by Germaine Greer & Made In England by David Malouf

by Morag Fraser •

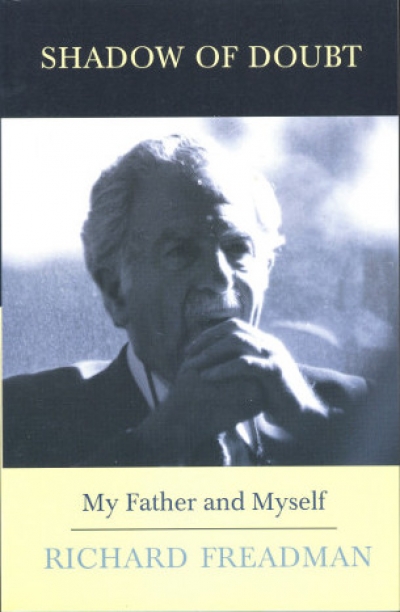

Shadow of Doubt: My Father and Myself by Richard Freadman

by Peter Rose •

Don’t Tell Me, Show Me: Directors talk about acting by Adam Macaulay

by John Rickard •