Memoir

Left Bank Waltz: The Australian bookshop in Paris by Elaine Lewis

by Carol Middleton •

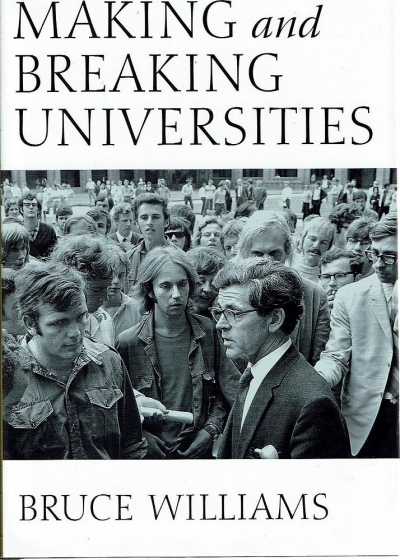

Making And Breaking Australian Universities: Memoirs of an academic life in Australia and Britain 1936–2004 by Bruce Williams

by Ros Pesman •

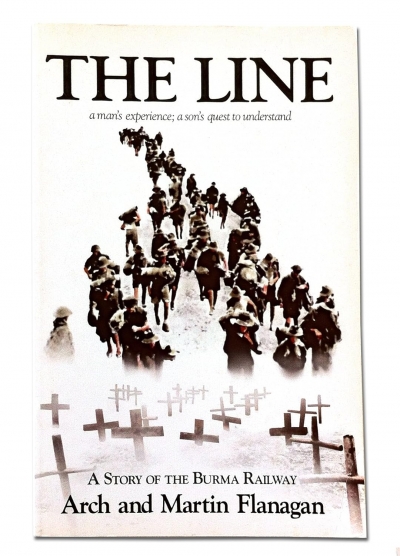

The Line: A man’s experience; a son’s quest to understand by Arch and Martin Flanagan

by Dan Toner •

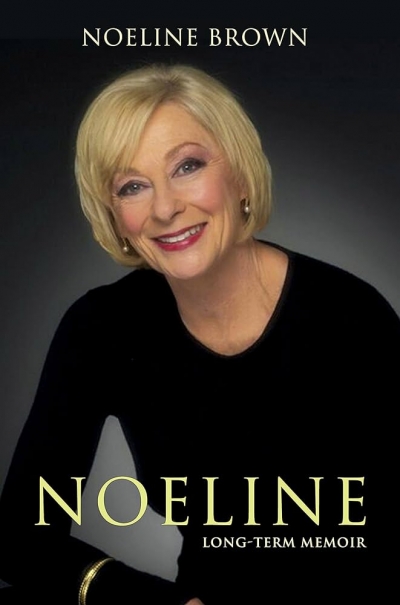

Noeline by Noeline Brown & Much Love, Jac X by Jacki Weaver

by Richard Johnstone •

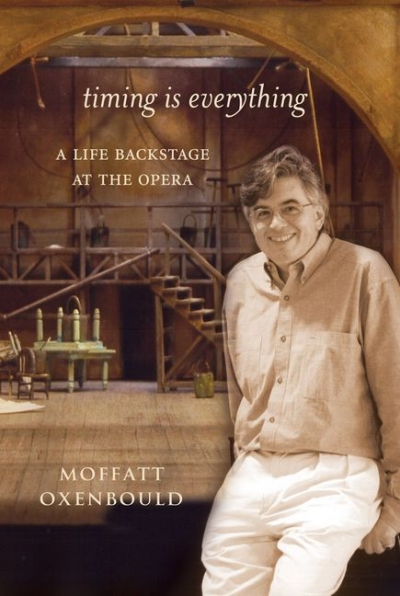

Timing Is Everything: A life backstage at the opera by Moffatt Oxenbould

by John Slavin •