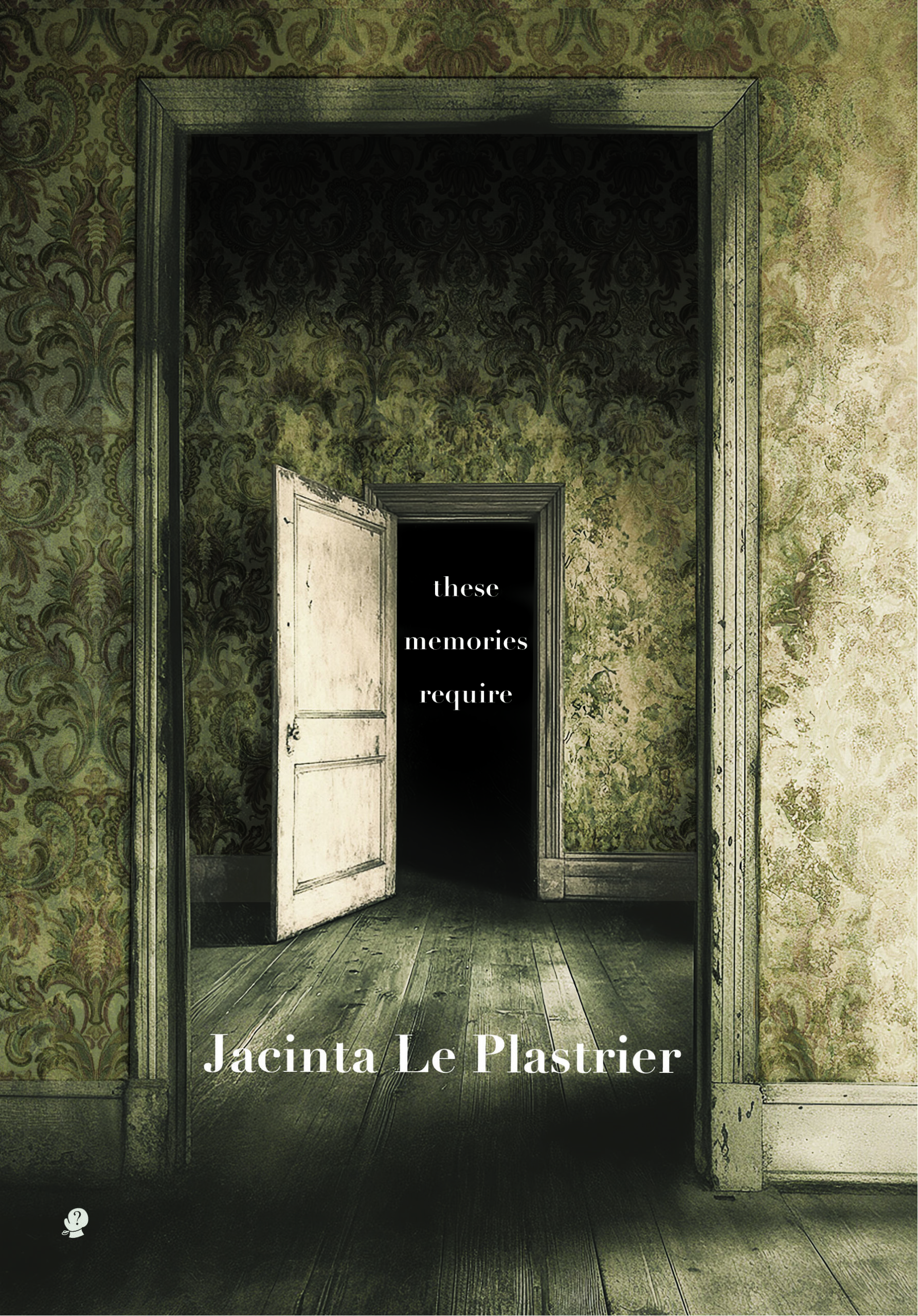

On David Malouf: Writers on Writers

Black Inc., $17.99 hb, 108 pp, 9781760640392

On David Malouf: Writers on Writers by Nam Le

For more than a decade the world has waited, patiently or disbelievingly, for a second book from Nam Le, author of The Boat (2008), a collection of seven tales that won the young Australian author acclaim throughout the world. Finally, it has arrived. A book-length essay running to about 15,000 words, it may not be what the ravenous world had in mind, but it is seriously interesting – interestingly interesting one might almost say. The volume appears in Black Inc.’s neat little Writers on Writers series, with its owlish photographs of authors and subjects: author on top, subject below. Until now, there have been four in the series, including Christos Tsiolkas on Patrick White, and Ceridwen Dovey on J.M. Coetzee. (Michelle de Kretser on Shirley Hazzard, due later this year, promises to be a notable pairing.)

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (2)

Nam Le's essay is challenging, instructive and deeply thought provoking. Some have suggested that it is more about Nam Le than it is about David Malouf, and that he has not done his subject justice. I profoundly disagree. His work in this essay has sent me back to rereading David Malouf's writing, much of which I had half forgotten. That to me is proof enough that the essay is a success. And it has not only made me reread 'The Boat', but long for more writing from Nam Le's pen. I hope he won't disappoint us by another long interval before he publishes again.

A quick look on google also brought up - in a short space of time - - "Irish- Australian crime author", "Irish-Australian cellist", "a German-Australian author" etc. etc.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.