2019 Porter Prize Shortlist

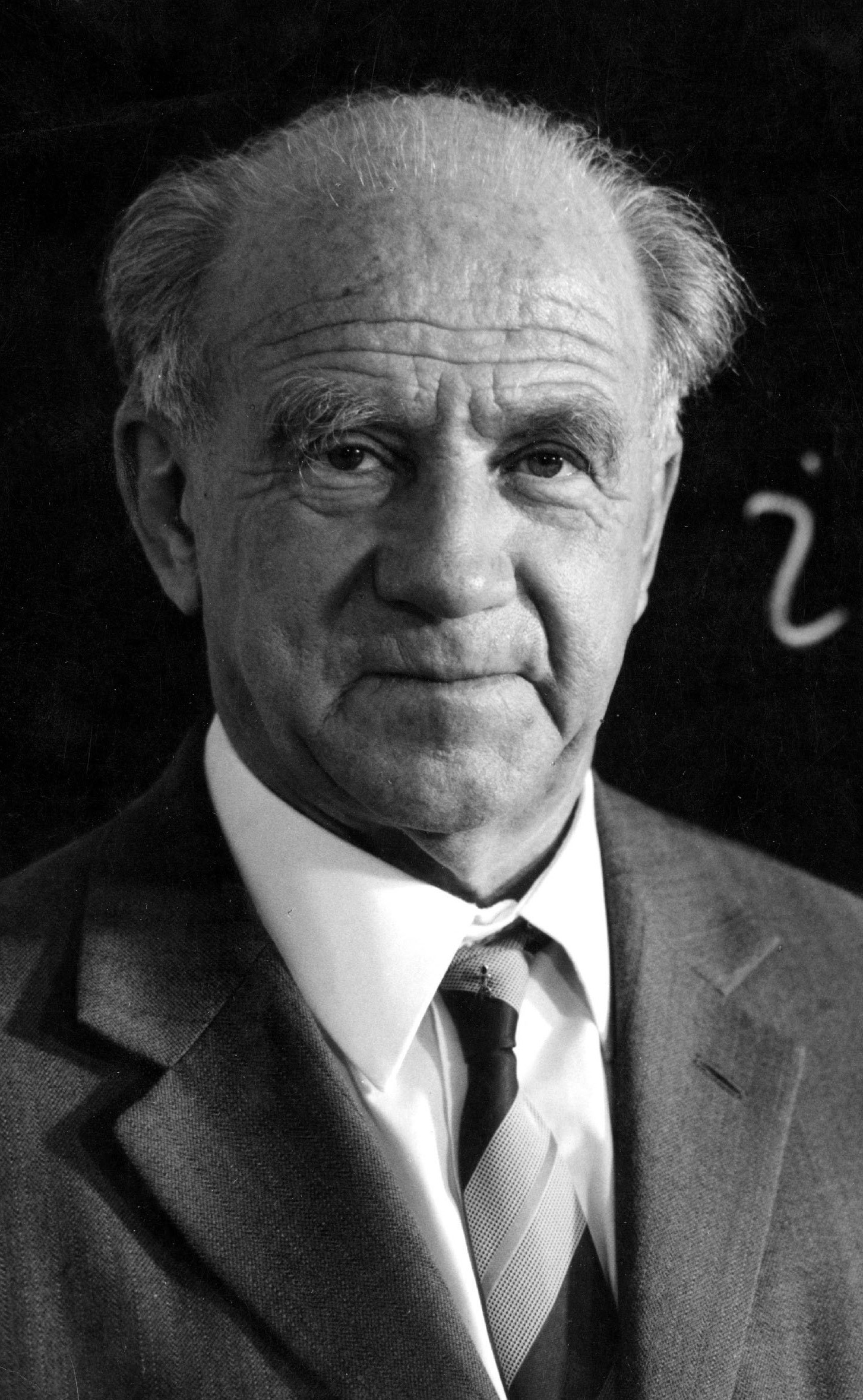

Dancing with Stephen Hawking

For Melinda Smith

I was living in England. Punk days, they were.

On my way to the party, I fell and scraped skin

from my knees, tore my stockings. No matter,

they were punk days, and I looked the part –

black-root blonde, make-up slurring my face.

And there she was: He wants to dance with you.

And there he was, seeping into his chair, mind

in the machine. From a distance, I’d thought him

all thought, the body’s ruin savaging desire,

but something simmered there. He rolled across

the wooden floor like a ship leaving harbour,

adrift on a wide sea. I did my best punk moves,

spasmodic thrusts and jumps, while he swayed

left then right in his choreography of wheels.

I tried not to stare. We moved until the music

slammed into silence, left everyone talking

too loud for a moment, like the noise of insects

in the dark. I don’t recall talking at all, only

the time given … Walking to the station,

I stopped, looked up to a moonless sky,

wondering whether that cloud was a cloud

or a galaxy. And I thought of the dance

of asteroids, the merciless pull of black holes,

red giants and white dwarves, breathless

nebulae. I thought of the atoms in my eye,

spinning and spinning, and the torrent of light

surging through me, soaking me to the bone

as I stood looking up, with my bloodied knees.

John Foulcher

John Foulcher has written eleven books of poetry, most recently 101 Poems (Pitt Street Poetry, 2015), a selection from his previous books, and A Casual Penance (Pitt Street Poetry, 2017).

The Mirror Hurlers

for Joyce Lee

1. The Looking-Glass Apprentice

Mistress, I’ve seen the sunlight swim on red brick walls. I’ve watched your mirror fly

from a high window. I remember the crash. It hit backwater bedrooms, distant kitchens.

The frame had shattered but the uncracked mirror flashed, a pool amongst ruins.

I saw my face in it, then your voice flooded the laneway. ‘Try it. Mirror hurling

goes back centuries.’ I grab my full-length mirror, stagger to the bedroom window.

The mirror leans against my shoulder, a cape made of myself. The brick wall opposite

moves in the heat. I turn around and cart the mirror back to its dark corner. And you talk

of leaving. Mistress, I know you want real height, sky streaming in at your front door,

unbroken mirrors scattered across the earth, but show me survival again. Think of me here

climbing the stairs in terror, lanes like canyons around me. All my mirrors unhurled.

2. The Mirror

This is my sworn story of staying whole. My owner knows it backwards.

I dreaded slippery-fingered servants, but when the mirror mistress picked me up

it was like a kept promise. When she threw me, I flew through my cousin

the window, and the air whispered of weightlessness. Falling was a new way

of being held. The crash was a savage cradling. I lay there taking in faces, safe

in the sacrificial wreckage. Now my unbreakable shine waits for you all.

Come to me for the backhanded truth of who you are. See, your left hand

knows only too well what your right hand is doing. Your crooked smile

slants the other way. And notice the fake depth in your eyes, your thin

visiting presence. Stranger, I give you your shallow reversed self.

3. The Mirror Detective

I know them. Their two-faced ways, their almost invisible

shimmers of thought. They are thieves, stealing mirrors

and hurling them into the world. They won’t get away with it.

I am after them, with my dull routine and my non-reflective mind.

I’ll hunt them down. I’ll climb the stairs, knock on the last door

and there it will all be: suspiciously open windows, mirrors in mattresses,

tables littered with wrecked frames. Mirror hurlers at work.

They’ll soon find out their mirror hurling days are over.

I’ll let them know that prison mirrors are made of tin.

They will put on their long coats. I will frisk them for mirrors.

4. The Mirror Lovers

There are those who will never release their mirrors.

They cannot surrender their perfect self-portraits.

They sleep with them. They wake up beside themselves

in dim rooms, and wonder if they have married.

All day there’s a quicksilver gleam in their eyes.

They feel strangely flat. They have to resist

an impulse to mime the movements of others.

Their minds are full of unwanted reflections.

At night, they return to the mimicry of marriage.

The fingertip touching, the two-dimensional tenderness.

5. The Mirror Mistress

I loved the lanes,

the early morning shudder of sun across old brick.

But here on this cliff top

with its mountains of pure space, I know I have come home.

Looking-glass lakes are scattered across the earth,

my run-up takes me

right to the edge.

I let the mirror go and everything seems to slide.

I am wiped from the mirror’s mind.

I am replaced by sky.

Ross Gillett

Ross Gillett lives in Daylesford in the Central Highlands of Victoria. His book The Sea Factory was one of the Five Islands Press New Poets 2006 series. His next book will be published by Puncher & Wattmann later in 2019.

Searching the Dead

The bone-coloured branches of the rusty fig

twist and rise into a canopy of leaves that shuts

out the beating sun. It’s like standing in a limestone cave

and gazing up at limbs that resemble toned calves

and bulging biceps. As if the tree has been fashioned

out of human body parts miraculously glued together.

From a distance it appears sublime, but standing beneath it,

I can’t shift these images of haunches, thighs and elbows.

The human form, even when you’re not looking for it,

is everywhere. Five days out from Nui Dat, after the firefight

and the ambush, I went back into the rubber plantation

to search the pockets of the dead. They weren’t our dead,

our dead had been dusted off that morning, but here

were men who resembled us, soldiers who had been trained

to follow SOP, move carefully day and night, minimise risk.

Clothes now stretched tightly over bloated arms and legs,

feet cold and green, flies and gnats crowding around

their eyes, their mouths. Bodies washed clean by the rain,

a few with legs completely missing, one or two

without heads. We were searching for intelligence.

I found a gold American watch, sunglasses, a plastic comb,

a bag of uncooked rice, a lock of hair. Occasionally,

what appeared to be a diary, filled with Vietnamese script,

a pressed flower fluttering down to the ground.

A cowrie shell bringing the news from the South China Sea.

In one man’s pockets a pair of lacy black knickers.

And photos wrapped in plastic to preserve them –

a girlfriend leaning against a motorbike, a couple posing

near a lake, a family in front of a shimmering pagoda.

Everything smeared with the same red dust that coated

my skin. There won’t be another photograph of this man

sitting with his children as he tucks into a steaming soup.

The rubber trees had been hit by bullets and dribbled

latex, as if they were crying. Johnno and Boffa

were digging a mass grave. I took my shirt off

so I could feel the sun on my back. I might have been

fielding at square leg, dreaming of the tea break.

When I opened a tin of tiger balm or laid down a pack

of playing cards, this shiver spread from my neck

to my shoulders. I was so aware of my body, how

it was greased and primed, how it wasn’t going to jam.

What I collected I put down by the base of the banyan tree,

the wood darker than this fig, soldiering on through

the hot afternoon, soaked with sweat. I was elated to be alive.

The work had to be done before we could move out.

I made a shrine to lives well lived, then went to find

some cool water to drink, some fresh air to breathe.

Andy Kissane

Andy Kissane has published a novel, a book of short stories, The Swarm (Puncher & Wattmann, 2012), and four books of poetry. His fifth poetry collection, The Tomb of the Unknown Artist, is due in 2019.

63 Temple Street, Mong Kok

Remember 63 Temple Street, Mong Kok?

Remember that cha chaan teng,

Mrs Suen, the owner?

Sorry, that jars your ears.

Remember ‘leave ice’, ‘fly sugar leave milk’, ‘tea go’ –

the waiters’ breaths, like shooting stars?

Sorry for the monosyllabic dictums.

The imperatives chase me back with their voracious tails

to Mrs Suen’s cha chaan teng:

go, leave, fly.

Remember the deep-fried peanut toast –

a square button of butter, egg tassels,

slurry glass eyes of a honey stripe,

and the sweet full-cream condensed milk?

Mrs Suen uses Carnation’s

condensed milk

from the contented cows of Australia

– as she says.

As for the peanut butter,

her preference is USA’s

Planters’ Crunchy, the nuts clutter

but melt like mercy – as she says.

Remember me? Mrs Suen asks.

Remember

the already remembered?

All of us remember –

yet only some grasp the gyration of the remembered.

How can I not remember? Mrs Suen! I reply.

For fifteen years at daybreak the lukewarm TV gargles –

‘Welcome to Hong Kong’s Morning.’

Every day I eat deep-fried ghost, drink mandarin ducks, no milk, no sugar.

A diet to keep myself forgotten.

I didn’t forget you, Mrs Suen says.

But all of us forget – yet only some let go of the gyration of the forgotten.

How not to break the fluid egg yolk on my doll noodles?

Slightly tilt the egg’s fringe up with your chopsticks and pinch –

but the translucent membrane still cracks.

It doesn’t forget the way to brokenness, and neither do I.

Grandma sipped the braised pork belly, her last ritual in the hospital.

The rain breaks its back.

It reaches out its little hands

and cut them off in front of me.

It says, Follow me. And just as I follow, it vanishes,

and multiplies.

Here’s my mobile number, I forgot yours, Mrs Suen says.

Laozi says – ‘She forgets it. That’s why it lasts forever.’

Did she trade her memory for the eternity of my number?

The rain finds its path to remember,

and falls on every person,

wanting –

I: One tea set, please.

Waiter Kuen: Tea set’s sold out.

I: A fast set, then.

Waiter Kuen: No fast set today.

I: I’d have a constant set, anyways.

Waiter Kuen: Constant set is fast set, fast set is tea set.

a fate of return – the rain and Waiter Kuen’s back.

Now the rain’s a searchlight: a black dog sniffs, a black car follows.

There’s no way to see how the rain enters.

You still have much black hair, Mrs Suen, I say.

The rain, stumbling upon its hands, tries to grip a larger surround.

Thanks to the braised pork belly, Mrs Suen jokes.

O, O, what a slice! Grandma exclaimed.

The fat broke loose on her tongue.

She never woke up again.

A raindrop is very quiet on my lips.

It melts into a shore afar – to where?

A red bean sneaks out of my glass.

I lick it back – to where?

I forget to give Mrs Suen my mobile number.

The rain has no proper path to rise back as rain.

How does hunger enter me?

I forgot the first bite in my life. I forget why I forgot.

Coolness sprawls flat on my tongue.

I can’t even give it a name.

Belle Ling

Belle Ling is a PhD student in Creative Writing at The University of Queensland, Australia. Her first poetry collection, A Seed and a Plant, was shortlisted for The HKU International Poetry Prize 2010.

Raven

Listen, my friend, this road is the heart opening

Mirabai

Out walking Sunday morning, the light wintering

Again inside the start of spring, a raven

Overflies me, and the yaw of its wings,

As it banks a little in the blank verse

Of the Sunday air – for no reason

It knows – the groan of wingbeat is, I think,

The sound my heart makes opening again each day,

Reluctant at first to get about the work

Of bearing my body through all it wants and misses,

And through the weightless freight of waiting out

The gloom that doesn’t want to still. But still

One lets it open, whingeing on its hinges,

A sly hope refusing to call time.

And making slowly through the silver gums,

Their shade a drapery of all the clothes

One’s lovers used to shed, a single feather

Fallen from another bird – nib

End planted in the turf – flares some blue,

Shows some indigo, inside its mourning

Garb. And this, I think, is the nature of things:

The fierce persistence of the wild within

The ordered world; this is a love you felt

You must let fall, which will not let you slip.

This is the work you leave, unmade yourself

By all you’re called to make, the love, the space

For everything you barely understand.

At home, you stand it in a glass, and start

Again. Word by word, beat after beat,

Putting pain to use, feathering forth

The silence out of which the future comes.

Mark Tredinnick

Mark Tredinnick is a poet, essayist, and writing teacher. His books include The Little Red Writing Book (2006) and the landscape memoir, The Blue Plateau (2009). He was co-winner of the 2008 Calibre Prize for his essay ‘A Storm and a Teacup’.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.