Richard Flanagan

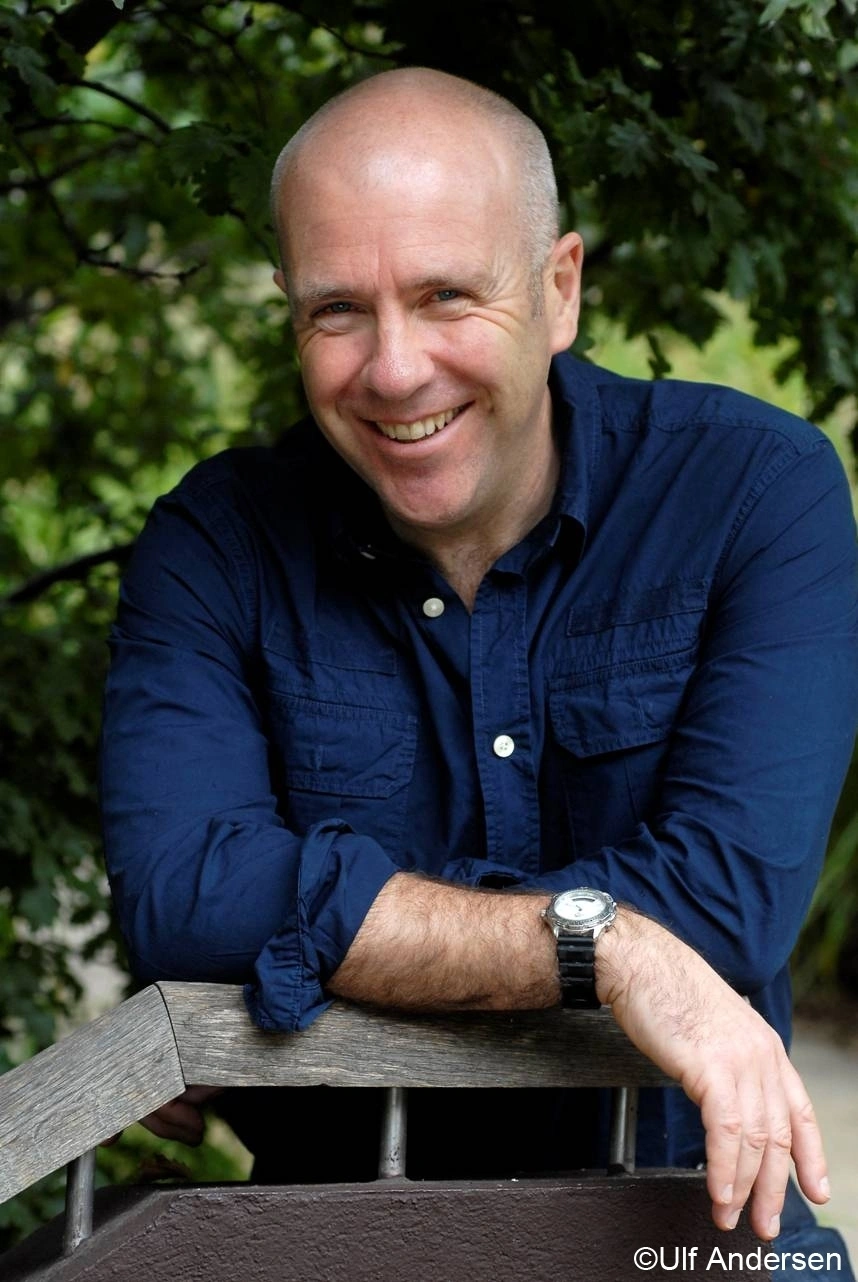

Richard Flanagan (photograph by Ulf Andersen)

Richard Flanagan (photograph by Ulf Andersen)

Richard Flanagan is an award-winn ...

When Richard Flanagan won the 2014 Man Booker Prize for his sixth novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, it was not the first time that he had won an international fiction prize; his third novel,

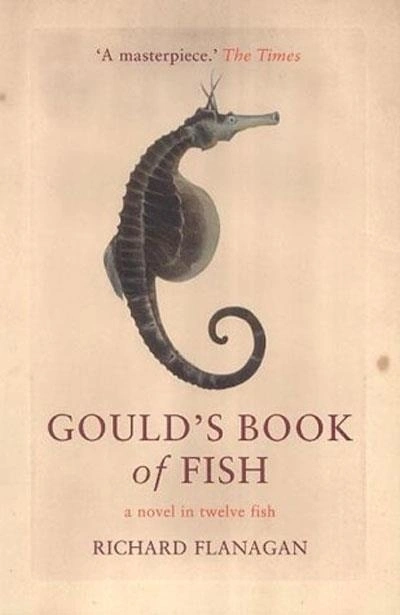

Picador has done rather well in this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award (worth $28,000), with three of the five short-listed novels: Richard Flanagan’s Gould’s Book of Fish, Joan London’s Gilgamesh and Tim Winton’s Dirt Music. Completing the quintet are Steven Carroll’s Art of the Engine Driver (Flamingo) and John Scott’s The Architect (Viking). The winner will be announced in Sydney on June 13.

Perpetual Trustees has been kept busy with short lists, including the one for the 2002 Nita B. Kibble Literary Award for Women Writers. This one, to be announced in Sydney on May 7, is worth $20,000. Three works in different genres have been short-listed: Marion Halligan’s novel The Fog Garden, Jacqueline Kent’s biography of Beatrice Davis, A Certain Style, and Hilary McPhee’s memoir, Other People’s Words.

... (read more)