Australian Art

The World of Norman Lindsay edited by Lin Bloomfield & A Letter From Sydney edited by John Arnold

by Nancy Keesing •

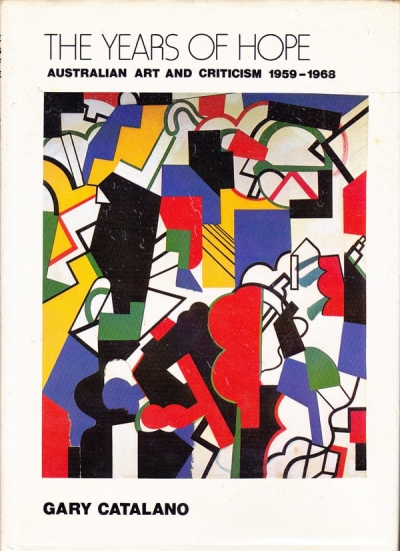

The Years of Hope: Australian Art and Criticism 1959–1968 by Gary Catalano

by Mary Eagle •

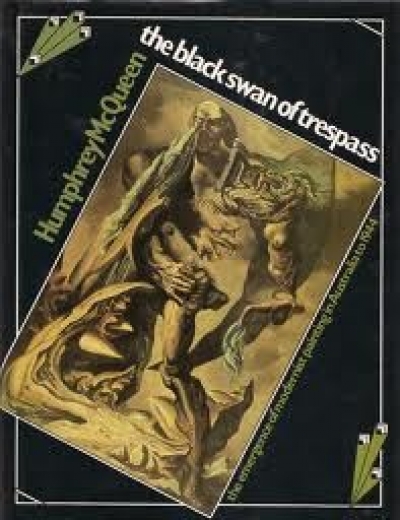

The Black Swan of Trespass: The emergence of modernist paining in Australia to 1944 by Humphrey McQueen

by T. Counihan •

Ian Fairweather by Nourma Abbott-Smith & Conversations with Australian Artists by Geoffrey de Groen

by Gary Catalano •