An die Nachgeborenen

‘Welcome to the Netherlands!’ the sign says in Dutch and English. The Schipol customs official inspects my Australian passport. ‘Nederlands geboren,’ he sniffs. ‘Zo je komt terug.’ So you’ve come back, he adds, in a tone suggesting that I might have left something behind minutes ago, rather than decades. ‘Skippy!’ He stamps my passport viciously. I consider a withering retort, but there are soldiers patrolling in pairs nearby, machine guns slung across their chests. Hours before my plane landed, eleven illegal immigrants burned to death in the prison facility at Schipol. Edginess pervades the airport.

I have returned to the Netherlands to have a specific conversation with the past. I would prefer to have this conversation in Dutch. Unfortunately, that useful English concept ‘the past’ – with its emotionally laden baggage trailing into near and distant history – is linguistically impossible in Dutch. At one extreme, there is the phrase: ‘verleden tijd’, the strictest meaning of which is ‘dead times’; at the other, ‘vroeger’, a sort of flat Dutch close to the English ‘olden days’, an indefinite gesture to an unspecified era. The fluidity, the emotional creak with which one can summon ‘the past’ using English, is not possible in Dutch.

Better, then, to slip and slide between the languages, stumbling up and down the treacherous slope of bilingualism. Try to make some sort of landing.

I am sitting outside a café in the markt, the square of Middelburg, the provincial capital of Zeeland, the most south-western province of the Netherlands. Northerners, such as the free-wheeling residents of Amsterdam, think of this area as the deep, intractable south and rarely visit, which suits the southerners just fine. This is where I come from. I am a Zeelander. Zeeuws. Middelburg-born and bred. This is the heartland of Calvinist Protestantism. Zeeland was one of the first provinces to join with the House of Orange to throw off the Spanish-Catholic yoke and has never allowed the royal house to forget it. The Zeeuws see themselves as forthright and determined. Others see us as stubborn, bloody-minded and unforgiving.

Zeeland is a recent geographic addition to the planet’s past, created over the last ten thousand years from the silt washed down from the great rivers of central Europe.

What the rivers of Europe deposit, the North Sea battles to subtract. This is a land of massive sea dykes, triumphant tales of reclamation, and tragic sacrifices to the sea. The provincial standard of Zeeland shows a lion half submerged in water, and carries the Latin declaration Luctor et Emergo, I arise from disaster. The unofficial motto of Zeeland is ‘Never Forget, Never Forgive’.

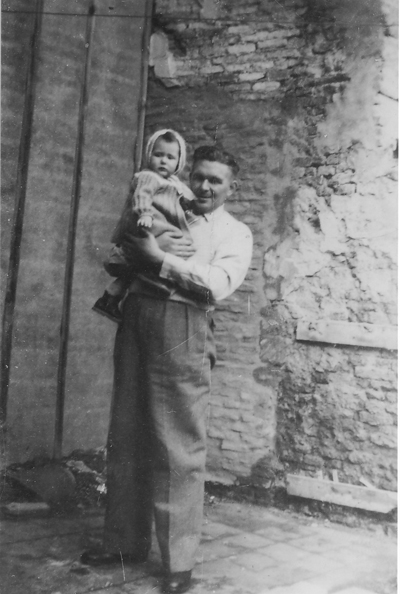

Elisabeth Holdsworth’s paternal grandparents (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Elisabeth Holdsworth’s paternal grandparents (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Middelburg lies at the centre of a former island, Walcheren, a long nose poking into the North Sea. When I was a child, Walcheren was still an island. Indeed, the land-neck joining Walcheren to the rest of Zeeland is so narrow, so tenuously held by a defiant army of dykes, that Walcheren may yet become an island again should sea levels rise. The watery arms of the east and west Schelde surround Walcheren. During World War II, the German North Sea fleet anchored in the Schelde off Vlissingen, south-western side of Walcheren. They used the shipyards at Vlissingen to repair their ships, with Dutch slave labour. Whenever the Allied bombers flew over the shipyards, men sang the national anthem and waved the standard of the House of Orange, symbol of the Resistance, even as Nazi machine gunners mowed them down.

My father and his three brothers avoided being taken to Vlissingen by joining the Resistance. Their life expectancy wasn’t any greater than it would have been had they worked for the Germans. Twenty-three thousand Resistance fighters died for the freedom of the Netherlands, my father’s two younger brothers among them.

‘Twenty-three thousand Resistance fighters died for the freedom of the Netherlands, my father’s two younger brothers among them.’

In November 1944, to liberate the Netherlands and begin the final push into Germany, the Allies, with the help of the Resistance, blew up the dykes protecting Walcheren from the sea. In some parts of Middelburg, the highest point on Walcheren, the water rose to two and a half metres above street level. The rich silt plains surrounding the city were obliterated. The Americans and the British trapped the Germans on Walcheren between their amphibious vehicles and the deep waters of the western Schelde. The surrendering Germans were herded onto the same trains that had transported a quarter of a million Dutch Jews to the concentration camps and ‘escorted’ them from the Netherlands.

Although I possess pieces of paper declaring me to be an Australian citizen, Zeeland is my heritage, the land of my nightmares, my past. No matter how much I try to infuse my brain with kangaroos and drought-riddled plains, I am enraptured by the land of my birth.

In the seventeenth century, Middelburg was the second city of the Dutch East India Company, after Amsterdam. Middelburg is small, the population less than forty thousand, yet the public and private buildings are grand, outsized – reminders of that wealthy time. My father’s family was part of the fabric of Middelburg and Zeeland since the thirteenth century. Their fortune rose as the Dutch East India Company prospered, and fell when that tune stopped playing. When Father was born in 1910, the family was still one of the wealthiest in Zeeland. My mother was also born in 1910, to a poor Jewish family in a sequestered community in an impoverished part of Zeeland called Zeeuws Vlaanderen – Flanders. Her parents and most members of their community were illiterate.

In 1910 both families shared the riches of children, the certain knowledge of continuity. I was the only child born to either family after the war. I am the last survivor of both families. I don’t have children, so it all ends with me. But not just yet.

I am sitting outside a café in the markt of Middelburg on a Sunday in November 2005. The day is so warm I have removed my coat, hat and gloves. In the Novembers of my childhood, I waded to school across the markt through snow, ice and winds so fierce they whistled through the holes once occupied by my baby teeth. This café is the same one my parents and I lunched at most Sundays after church. Mother and Father always chose this particular position, perhaps this very table, because the Stadhuis, the town hall – the gothic structure from which the rulers of Zeeland governed the province for six hundred years – is directly opposite.

When we dined here in the 1950s, the Stadhuis was a pile of war rubble covered with scaffolding. My father, a keen amateur photographer, had no trouble fitting what was left of the Stadhuis within the sight of his camera. No matter how I jiggle my camera, I can’t get the whole building and spire within the frame.

In Zeeland, food and alcohol may not be served on Sundays until the Protestant God says so. While waiting for the church bells to ring, I dip into the Volkskrant, the centrist newspaper founded by the Resistance during the war. The mild November weather has the Volkskrant in a spin. A large part of the glossy section is devoted to climate change. According to the Volkskrant, this is the warmest autumn since records began. Over the last thirty years, the Dutch growing season has been extended by almost three weeks, adding billions to the economy. For the moment, the Netherlands is benefiting from the warming of the planet.

Plumes of cigarette smoke gust out of the restaurant. Dutch attitudes to smoking are infuriating. I have had jousts with fellow hotel guests who light up as soon as they enter the breakfast room. I have nearly been run over by bike-riding maniacs whose hands can’t make contact with the handlebars because they have a mobile phone in one hand, bottled water in the other and a fag in their mouths.

The church bells are ringing: single, dour notes from the Dutch Reformed church; carillons from the Catholics. I may now order food and a drink. My parents adored the Zeeuws specialty (grilled mussels). I hated the greasy, gritty molluscs back then. Now that I have a mature and sophisticated palate, perhaps I will enjoy them.

A party of young Germans in hiking gear investigates the inside of the café. They emerge fanning their faces, overwhelmed by the cigarette smoke, and join the non-smokers outside. They study the menu, which is printed in Dutch. The waiter who attends them has mislaid his ability to speak German. He claims he can supply gebroken Engels (broken English) and that the chef is proficient in Japanese, but German … das is nicht … he throws his hands into the air.

Using English, the Germans order fish and chips. One of the party, a young, dark-haired girl, extracts a notebook from her pack and begins writing. She sniffs and swivels her head, no doubt in search of local colour. I return to the Volkskrant.

Paris is burning. Disaffected, marginalised youth are warning the French that they are no longer prepared to be an underclass. There have been riots in Rotterdam. The Dutch immigration minister has attended a memorial service at Schipol for the detainees who burned to death. Candles have been lit, but Dutch government policies will not be relaxed. The Netherlands has the most repressive immigration policy of any European country.

‘Paris is burning. Disaffected, marginalised youth are warning the French that they are no longer prepared to be an underclass’

The Volkskrant revisits a simmering question, whether or not a Dutch army unit serving in Bosnia stood by, either knowingly or ineptly, while atrocities were committed. In a placatory, diplomatic move, a Dutch bomb squad, famed for its defusing abilities, has offered to assist with the cleansing of minefields in Kosovo.

Dresden Cathedral, bombed in the last months of World War II, has finally been restored. No representative of the Dutch government or the royal family will attend the rededication ceremonies. The Volkskrant reports that the ceremony will not be broadcast on free-to-air television in the Netherlands.

The party of Germans at the next table is talking loudly and animatedly about soccer. The Australian Socceroos, coached by a Dutchman, have defeated Uruguay in a prelude to the 2006 World Cup. The Volkskrant reports that some Dutch soccer fans have announced their intention of travelling to Germany for the finals matches dressed in orange and wearing German helmets. The Volkskrant expresses half-hearted disapproval of the wearing of German helmets. Orange, the standard of the royal house of Orange-Nassau, is everywhere. As orange is inextricably connected with Dutch Protestantism, this seems rather too bad for Catholics, Muslims and the few Jews who survived the war. To my father, orange was the symbol of the Resistance. The flag flown from the roof of our house was the tricolour of the united provinces. I wish he was sitting here opposite me in this café in the markt, in Middelburg, so that I could ask him what he thinks about all this orange business. We might share a laugh about the Dutch army and the cleansing of minefields.

Elisabeth Holdsworth (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Elisabeth Holdsworth (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

After the war, the Germans left the open country around Middelburg littered with mines. The inner city, the binnenstad, had been flattened. My parents’ house – like those of most of my friends – was only partly habitable. The back of our house was a memory, our once famous eighteenth-century garden a bomb crater. Whenever the weather was fine, my friends and I roamed unconstrained in fields outside Middelburg that had been cleansed. We didn’t yearn for a backyard: the whole of our shattered city and the open expanses of Walcheren were at our disposal.

‘After the war, the Germans left the open country around Middelburg littered with mines’

Our parents were involved with the reconstruction of Zeeland. (Dutch has about a million words to convey reconstruction after wars, flood damage, civil wars, religious wars etc.) We, the children born just after the war, were a blessing and a burden: a blessing in that we were born at all; a burden because our parents were so preoccupied with the rebuilding and with regaining their psychic strength in the aftermath of the war they did not know how to cope with us. My friends and I – four boys, two girls – formed a special unit. We had all been struck down by the rheumatic fever epidemic of late 1949. The medical profession regarded our hearts with suspicion. We were prevented from attending kindergarten, then we were judged too frail to start first grade.

My mother didn’t work in the sense that she earned a wage. Father’s family was too grand to have one of its women working in other than a voluntary capacity. Thus Mother volunteered to look after us. Although we loved roaming when school was in, pitying the poor saps locked up in classrooms, we were hungry to learn. In the afternoons, when we were supposed to be resting our weakened hearts, Mother taught us to read and write. She called us the Nachgeborenen – those who come after – in honour of Bertolt Brecht. She knew his poem ‘An Die Nachgeborenen’ (written in 1939 as Germany was invading Poland) by heart, in both German and Dutch. When she was distracted by the inner turmoils that bedevilled her and muttered ‘Wirklich ich lebe in finsteren Zeiten!’ (Truly, I live in dark times), we knew we were in for a few rough hours.

We were confused by Mother’s use of German – she was supposed to be a Jew – but at the age of six we didn’t agonise too much. My closest friend, Fritz, the lord mayor’s son, told us not to listen to what Mother was saying, but rather to live in her voice which, to the end of her life, carried the telltale signature of her first language, a dialect infused with Yiddish and Flemish. Most of the time, this tactic worked. However, if Mother caught us daydreaming, she threw whatever book was at hand at our unwary heads. Fritz earned a bloody nose this way, one of the other boys a bruised ear. Mother was beautiful at a time when physical beauty only existed in the world created by Hollywood. Everyone else around us was too physically affected by the ravages of the war to be considered anything other than passable. Mother’s auburn hair and flawless complexion fascinated my friends. She was rumoured to be one of the thirteen hundred Dutch survivors of Dachau. My friends urged me to ask for details. Too afraid of Mother’s mood swings, I never did.

‘Mother was beautiful at a time when physical beauty only existed in the world created by Hollywood’

We were beset by boundless curiosity to see what lay at the edge of our world. We longed to find war booty, a German helmet, anything marked with a swastika. On fine mornings, we left Middelburg and the wreckage of the binnenstad, with packets of sandwiches, books and, if we were lucky, a piece of fruit. Oranges were the price of gold after the war.

The flooding of Walcheren in the liberation of 1944 had killed the ancient spreading elms and beeches that had graced our island for centuries. The only trees we knew were poplars marching over flat land to an infinite horizon.

One day, we ran toward a row of dunes. I can’t remember why. We had few reasons for anything we did. Before we reached the dunes, we were surrounded by lightning which struck the ground in a crazy dance. We ran on between raindrops the size of eggs, arms and legs flailing, knowing we had to avoid the poplars; their upright stance acted like a magnet for the violent electrical storms that ravaged our island in summer.

We came to a barbed wire fence and crawled underneath into a field pocked with holes and wires poking out of them. ‘Alien antennae!’ Fritz and I yelled at the others. We were addicted to a serial on the radio in which aliens figured prominently. Above the noise of the thunder and lightning, we didn’t hear the voices booming from loud hailers telling us to move away. Finally, through a gap in the storm, we heard them and walked reluctantly to the source of the angry voices. I gave one antenna a last delicious jiggle. Faces stared at us. Mouths opened in horror and moved in silence. Arms beckoned us urgently. Yet we strolled nonchalantly towards the army men. One of the men mimed tiptoeing. That looked like fun. We didn’t mind doing that. Near the fence, hands grabbed at us, dragging us roughly through the barbed wire. Then a mighty bang, leaving all of us, children and army men, covered from head to foot in dirt.

The soldiers escorted us to our respective homes. At the lord mayor’s residence, Fritz was dragged inside by the ear. I knew what would happen at my house. Mother erupted into a dreadful rage. She began to beat me, eyes wide, tongue protruding from between her teeth. Her blows rained about my head. When my father intervened, she tried to hit him. Father was over six foot tall, she no more than five one, so her fists thumped away uselessly. The soldiers snuck away. Mother’s rage subsided, followed by tears and a retreat to her bedroom.

Father tried to clean me up in the bathroom only recently reconnected to running water. ‘Don’t know what all the fuss was about. Those mines were half defused,’ he chuckled. ‘You might have lost an arm or leg at most.’ Father used black humour to cope with the effects of his war. He drank too much gin, smoked too many cigars, but he was the glue that held our family together. When he put me to bed later, he added: ‘Took us twelve years to have you. Too old to have any more. Appreciate it if you don’t die just yet. Tomorrow, I’ll go up to the school. You and your gang had better go to school before you blow up the rest of Walcheren.’

That night, the first of the Nachgeborenen died when his heart, damaged by rheumatic fever, stopped beating while he slept. The rest of us were not told until after the funeral.

At the end of summer, we were allowed into the first grade. After two weeks, Fritz and I were moved into the second, and placed at a desk at the back. Mother’s haphazard education had made us too advanced in some areas, woefully behind in others.

The Nachgeborenen, Elisabeth Holdsworth second from left, Fritz front centre

The Nachgeborenen, Elisabeth Holdsworth second from left, Fritz front centre

(photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

One of the young Germans at the next table is reading from a guidebook to Middelburg. ‘The Stadhuis was badly burnt in 1940 and had to be renovated. The renovations weren’t completed until 1976. Wonder what caused the fire?’ Although he is speaking in German, the other Dutch sitting around me understand. There is a collective raising of eyebrows, a thinning of lips.

The Netherlands had capitulated to the Germans. The royal family fled, firstly to England, where Queen Wilhelmina remained for the rest of the war, broadcasting almost daily on Radio Oranje. Princess Juliana, the heir to the throne, and her children sought refuge in Canada. The Gestapo had taken up residence in the Dam Palace in Amsterdam. The port city of Rotterdam, so vital to an eventual Allied advance, hoisted the white flags of surrender in order to save the city. The Germans realised they could never use Rotterdam as a port; the coast was too open and too close to England. On 17 May 1940, in the earliest example of blitzkrieg, the Germans bombed Rotterdam to the ground, into the sea and out of history. When the Luftwaffe was finished with Rotterdam, they turned south-west. From the attic of our house, in the centre of Middelburg, my parents watched the sky fill with the bomber squadrons. The Luftwaffe dropped so many bombs on the binnenstad of Middelburg, particularly on the Stadhuis, one of the finest Gothic buildings in Europe, that a fireball developed. The Stadhuis, the Abdij Kerk, a complex of abbeys dating back to the twelfth century, the markt and the surrounding streets were consumed by flames. Vlissingen – the port and shipyards – was bombed, but only enough to force the populace into submission.

’On 17 May 1940, in the earliest example of blitzkrieg, the Germans bombed Rotterdam to the ground, into the sea and out of history‘

In the four years until liberation, the island of Walcheren became a prime bombing target for the Allies. I have my family’s photographic collection, some dating back to the mid-nineteenth century. One poignant shot shows the Stadhuis and markt in 1939. On the back Father has written: ‘Zo was het voor de oorlog nu is alles verwoest.’ This is how it was before the war. Now everything is destroyed. Verwoest, however, means something more than mere destruction: the sense that a page in a dark night of history has been turned in a book that can never be reopened.

The author’s parents’ wedding, 1935 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The author’s parents’ wedding, 1935 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The mussels are gritty and make me feel ill, the same reaction I had as a child. I get up to leave. The young German girl has stopped writing. In English she asks me to take a photograph of her party. ‘I presume you are a tourist, like us,’ she says, pointing to my camera.

‘I’m Dutch,’ I say. ‘Born in this city just after the war. I live in Australia.’

She bites her lip. My German is good enough for me to suggest ways the youngsters might sit. Aim. Fire. The image on the digital camera shows them captured in all their youthful innocence. I ask the German youngsters where they are staying.

‘At the Rue de Commerce, opposite the station,’ they answer.

‘I’m sure you’ll be comfortable there. I’m at the same hotel.’ The Rue de Commerce was the headquarters of the Zeeuws Resistance during the war. They hid in the cellars and used the waterway immediately in front of the hotel to enter and exit Middelburg. It is a source of pride to the Zeeuws that everyone in Zeeland knew where the Resistance was housed, but the location was never betrayed to the Germans.

‘The hotel was built by a French consortium in 1886,’ I say to the Germans as I walk away, ‘and has an amusing history.’

A few streets beyond the Stadhuis is our family home: number 1, Singel Straat, a plain, unadorned house reflecting the Calvinist Protestantism of my father’s family. The blown-off rear of the house has been seamlessly restored. A plaque by the front door registers this as a site of historical interest, but does not mention that this is a resewn version of the original. I had forgotten how narrow the street was, yet how large the house: three storeys high and extending to the street behind. My grandparents lived opposite in number 2. Across the top of their house, a date is picked out in gold leaf: Anno 1743.

My parents, when discussing the bombing of Middelburg in May 1940, always ended the tale with the sky turning black with the planes of the Luftwaffe. They skated over the next part: hiding in the coal cellars until the German bombers went away. They dwelt lovingly and with much merriment on the detail that Middleburg had been so thoroughly bombed that the German high command hadn’t left themselves a building grand enough from which to govern the ungovernable province of Zeeland. The Germans ended up using the top two floors of the Hotel Rue de Commerce.

From the Singel Straat, the dome of the Oostkerk (the Dutch Reformed Church) – finished in 1667 and embellished with all the money available from the golden age – dominates the surrounding streets. The dome has a belfry to admit natural light rather than the candles associated with Catholicism. The Oostkerk was the first church in the Netherlands to be built by Protestants for Protestants. Most Protestant churches are stripped former Catholic houses. Inside, a tier rises facing the Predikant’s lectern. Father’s family name is inscribed on the most prominent row of pews. My ancestors sat there for three hundred years, looking down on the rest of the congregation, convinced of their piety and superior social status.

On the spot where Grandfather sat, as head of the family, there is a gold plaque below the armrest commemorating the deaths of his sons: the two who died during the war, and the eldest, Lijnus Hendrikus, murdered in 1945. Of Grandfather’s five children, my father was the only one to marry and produce an heir, a puny Nachgeborenen who contracted rheumatic fever in 1949 and might have died at any time.

Grandfather hated long sermons. Whenever the Predikant raved on too long, Grandfather banged his walking stick on the railing in front of him until the sermon ceased. Fritz and the lord mayor’s family occupied the pews on the other side of the church. Every Sunday I had to avoid catching Fritz’s eye in case I broke into uncontrollable giggles.

Grandmother was a saint. I knew this to be so, because she always wore long black dresses and a white coif to denote her piety. Around her neck, heavy gold necklaces were interspersed with creepy black beads. Grandmother, stiff-lipped, ramrod-straight, waited every Sunday for Grandfather to bring down his walking stick. As soon as he did she paused, widened her eyes, then bowed to the Predikant.

Mother rarely attended church. She was excused on account of her fluctuating moods and her Jewishness. The only time Mother attended church was when Father’s unmarried sister visited Middelburg. Tante Katrien was hofdame, lady-in-waiting to the former Queen Wilhelmina. Katrien had accompanied Wilhelmina into exile in England; after the abdication in 1949, she attended the queen in the crumbling palace, Het Loo.

‘In an era of shortages, combined with the Calvinist austerity that governed our lives, my mother dressed like a peacock’

In an era of shortages, combined with the Calvinist austerity that governed our lives, my mother dressed like a peacock. She made all her own clothes on a treadle Singer sewing machine, copying patterns out of magazines. We were supposed to be wealthy, but by the early 1950s that wealth, mostly gleaned from the Dutch East Indies, had evaporated. On the quiet, and to supplement her income, Mother made clothes for the ‘ladies’ of Middleburg. When Tante Katrien visited and attended church in her dreary black court costume that swished the ground, Mother made sure she wore a short dress to show off her shapely legs, and, if possible, a new, brightly coloured outfit to outrage the congregation.

Tante Katrien possessed a magnificent string of black pearls brought back from the East by one of my privateer ancestors. Katrien was not allowed to wear the pearls at court, as the House of Orange-Nassau did not possess black pearls. She made sure she wore them every minute of every day she was in Middelburg. I longed to stroke the pearls to test whether they felt as silky as they looked.

Tante Katrien disapproved of me. I was precocious, indulged, the product of an unsuitable marriage. She never addressed me directly, but referred to me as het kind, the child. Tante Katrien regarded me with distant, ice-blue eyes. I avoided them in case they made my heart stop.

Father’s family was baptised in the Oostkerk. I was baptised there, too. My first given name is a family name. My other two names, Miriam and Esther, came from women whom Mother befriended at Dachau and who died there. Mother often boasted that she fought Grandmother and Tante Katrien to stand in that Calvinist place to give me a Jewish legacy, implanted with all the burdens of a different past.

Elisabeth Holdsworth with Opa and Oma in Greode (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Elisabeth Holdsworth with Opa and Oma in Greode (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

I meet the Germans again in the bar of the Rue de Commerce. They summon me to their table for a drink. ‘We walked the Bolwerk,’ the dark-haired girl tells me. The Bolwerk is a linear park alongside a system of canals following the line of the medieval walls that once protected the city of Middelburg.

‘We loved the windmills,’ she says shyly.

Halfway round the Bolwerk there are two windmills, relics of a time when thousands of mills creaked and groaned throughout the Netherlands. Wind turbines and nuclear power provide Dutch energy now. Next to the mills is a Jewish cemetery for Orthodox Ashkenazi Jews. Before the war there were two synagogues in Middelburg, two Jewish schools. The Sephardim and Ashkenazi both had thriving communities within the province of Zeeland. These days the Jews of Middelburg meet in the front room of a private house. There are twelve chairs for the congregation.

‘We went to the Stadhuis as well, for the guided tour,’ the German girl continues. ‘The guide didn’t leave us with any illusions. My friends couldn’t stand it. They left after five minutes. I stayed for the whole tour.’

‘Good for you,’ I say. I can think of nothing else.

‘I’m Eva,’ she says.

The bar manager turns on the television to a German news channel. The broadcast shows excerpts of the re-dedication of Dresden Cathedral and a recap of how Dresden was carpet-bombed by the Allies and consumed by a fireball.

‘They’re replaying that match between the Skippies and the Uruguayans on the Dutch station,’ one of the German boys says. ‘Can we watch that?’

‘Ja! Come on the Skippies!’ a Dutch voice yells. The bar manager obliges and switches channels.

I wish the German youngsters a good evening and retreat to my room.

Elisabeth Holdsworth with her father (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Elisabeth Holdsworth with her father (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Although November has been unusually warm, the days start late and close early. It is nearly the shortest day. I breakfast at seven a.m., to a backdrop of darkness. The Germans enter and settle at a table near me.

‘Guten morgen, Mevrouw Skippy,’ they greet me.

‘Guten Tag,’ I mumble from behind the Volkskrant.

The young girl, Eva, crushes into the seat next to me. ‘We’re going to Flanders today.’

‘Zeeuws Vlaanderen? Or the Belgian part?’

‘We’re taking the ferry across to Breskens.’

Zeeuws Vlaanderen then. That had been my plan. If I don’t commit to this trip, I fear the weather will deteriorate. If I hurry I can catch the first ferry, avoiding Eva and her friends.

The train from Middelburg to Vlissingen is a mere two carriages long. Just as it is about to leave, the Germans clamber on board with backpacks. ‘Ah, there is Mevrouw Skippy,’ they joke familiarly. A quarrel breaks out between Eva and a young man who I presume is her boyfriend. I crack open the Volkskrant, determined to have nothing to do with them.

The train journey to Vlissingen is only fifteen minutes. The train connects directly with the ferry. Until recently, the ferry was the only way across the Schelde to Zeeuws Vlaanderen on the other side. Now there is a tunnel sixty-four metres under the Schelde, for cars and buses. The ferry takes foot passengers and bikes.

The Schelde, a shocking blue, is as still as a pond. I have seen advertisements promoting Zeeland as the Riviera of Northern Europe. Climate change might yet make this true. From the aft deck, the high-rise developments of Vlissingen are visible. Looking the other way, I can see plumes of smoke above Antwerp; from the forward deck, I cansee ugly blocks offlats fronting the water at Breskens.

Eva sits next to me. She has been crying. She looks sideways at me to make sure I have noticed. I want to wallow in the past. I don’t want to be involved in her story. I don’t want her to intrude into mine.

‘Have you had a fight with your boyfriend?’

She sneaks a hand into mine.

‘My husband couldn’t get enough time off work to accompany me on this trip,’ I tell her. ‘We’ll both be returning to the Netherlands in the Spring.’ The hand is retracted, replaced by an awkward silence. ‘Durng the war the German North Sea Fleet anchored off Vlissingen. See, Eva, where the land curves like a boomerang. They were impregnable there. Tactically very clever.’ She looks at me, confused. ‘Come to the railing. Where the water boils on the horizon, that’s where the Schelde and the North Sea meet. Any ship riding over the top is visible for miles.’ As I speak, a container ship rises leviathan-like to perch for a moment on the frothing water before descending into the Schelde.

‘What about submarines?’ Eva asks.

‘There were submarine incursions, mostly spying missions. The water is shallow where the two bodies of water meet. Even submarines had to rise almost to the surface, making them visible to the watchers on shore. In the end, the only way to defeat the Germans was to flood Walcheren. The Nazis didn’t appreciate Dutch history. The Spaniards, French and English were all trapped in the same way.’

We are almost at the midpoint of the Schelde. I can see Domburg and the glint of water surrounding Veere. Father knew the estuarine waters around Veere almost as well as the fishermen. In a wide-bottomed mahogany sloop, he slipped through the estuary, ferrying Allied spies in and out of the Netherlands. Although his boat wasn’t suitable for the deep rough water of the North Sea, on several occasions he had to continue to the other side, right up the Thames and into London. On these forays, he flew both the tricolour and the standard of the House of Orange as soon as he was in English waters.

‘The Nazis had a price on Father’s head that was second only to the bounty they were prepared to pay for the capture of German-born Prince Bernhard, Queen Wilhelmina’s son-in-law and Commander in Chief of the pitiful Free Dutch forces’

He could have stayed in England and joined his sister Katrien at Queen Wilhelmina’s court, but each time he returned to Walcheren. The Nazis had a price on Father’s head that was second only to the bounty they were prepared to pay for the capture of German-born Prince Bernhard, Queen Wilhelmina’s son-in-law and Commander in Chief of the pitiful Free Dutch forces. Throughout the war, Bernhard snuck in and out of the Netherlands to meet with the Resistance via the shallow waters around Veere. Neither Father nor the prince was ever captured. Neither ever received so much as a scratch. In his biography, Prince Bernhard jokes that the only time he was ever wounded was one of the occasions he visited Middelburg just before the final invasion. He and Father were drinking gin in the basement of the Hotel Rue de Commerce while the German High Command of Zeeland dined upstairs. The prince relates that he drank so much and laughed so much he fell off his chair and broke a rib.

‘That’s Domburg over there, below the dunes,’ I say to Eva. ‘When I was a child, the beach was covered with war debris. A Norwegian commando unit came to grief there. Those blocks of concrete are all that remains of German watchtowers. The Norwegians landed at night but the Germans saw them, turned their spotlights on them, and that was the end. Domburg was another impregnable position. Once I tried to add up all the Allied lives lost trying to liberate the Netherlands. I stopped when I came to a quarter of a million.’

‘What about the Germans who lost their lives?’ Eva asks, accusingly.

‘I don’t care.’

‘But … but ... we have forgiven ourselves,’ Eva is almost shouting.

‘Queen Wilhelmina never forgave you. Until her death she marched every year with the Veterans at Wageningen. That’s where Bernhard accepted the German surrender. Prince Bernhard continued the tradition of marching with the veterans until he too died.’ As I walk away from Eva, I sense her diving for her notebook.

Except for the jazzed-up ferry terminal and the high-rise towers, Breskens looks much the same: a gateway to a forgotten land. The narrow strip known as Zeeuws Vlaanderen clings to a shred of Dutch identity. Before World War I, this area, no more than fourteen kilometres wide, was Belgian. Mother was born in a village close to Breskens, called Groede. Her earliest memories were of the guns of the Great War. She saw the soldiers creeping through her village, trying to get to the Schelde. If they made it to the other side, they were in the neutral Netherlands and free.

‘Can I come please?’ Eva has followed me off the ferry to the bus stop.

‘I’m going to a place called Groede. There’s nothing for you there.’ Her eyes beg me. ‘Oh, come on then.’ Despite her backpack, she leaps across the tarmac like a gazelle.

The distance to Groede is only 3.2 kilometres. I could have walked. We are off the bus before we have properly settled. Surely the journey took longer in the past.

According to Mother, Groede personified the middle of nowhere – forty minutes from Bruges, half an hour by ferry, bus and train from Middelburg. Other villages close by are all equally insignificant.

In 1918 Queen Wilhelmina brokered a deal with President Woodrow Wilson to have this strip of land incorporated into the Netherlands. As soon as the Dutch obtained Zeeuws Vlaanderen, they forgot it existed. When Wilhelmina entered the Netherlands after the liberation, she did so via Zeeuws Vlaanderen, the first time she had visited since 1918. British amphibious vehicles then transported the queen across to the Schelde to the flooded lands of Walcheren. Wilhelmina was famous for never revealing her emotions, but when she saw the sacrifices the people of Walcheren had made, deliberately flooding their land, she fell to her knees in the mud and salt water and cried ‘Mijn volk! Mijn volk!’ My people. My people.

In a country of churches, where every village has at least two large edifices striving to point a finger at God, Groede has one sublimely ugly square box with a spire added as an afterthought, and a plaque near the miserable front door proclaiming that the village was settled by Lutherans in the 1740s. I spent some of the happiest hours of my childhood here. I always addressed my grandparents in Middelburg formally as grootvader and grootmoeder. My grandparents in Groede were Oma and Opa. As the only child of both families to be born after the war, I was accorded a special place. I basked and gloried in their unconditional love. Whenever I read aloud from a newspaper, Oma and Opa’s eyes lit up and the neighbours were summoned to witness the miracle of a child reading.

The village radiating from the ugly church has barely changed. Yuppies have discovered a few of the houses. Of the few shops – a bakery, a minuscule supermarket, a local museum – nothing is open, nor will be until spring, five months away.

Eva is circling me cautiously. Although the village looks and feels familiar, after walking around for nearly an hour I still can’t locate Oma and Opa’s house. Their dwelling was less than modest: old, but not historically significant. There is no reason for their house to be still standing, other than my wanting it to be so.

Down a narrow street, we discover a restaurant that is being renovated. The doors are open. ‘Can we get something to eat?’ I ask peering inside, past the carpenter’s mess. The proprietor says she can do an omelette. After lighting a cigarette, she disappears into the kitchen. She reappears with plates of buttered bread decked with a slice of cheese and a barely fried egg wobbling on top. She bangs the plates down in front of us. ‘It’s going to snow soon.’ The egg yolk dashes unattractively down the mound of buttered bread. As soon as her back is turned, I push the plate away.

‘Is het niet lekker?’ Isn’t it tasty? the proprietor asks on her return. I am tempted to tell her exactly what I think of her beastly food, but Eva sends me a warning look.

‘You’re intruding into my story.’

She laughs. ‘You can always edit me out. Like this Groede. This place feels edited.’

‘There is no sign now of the Jewish community who lived here. Nothing,’ I say to her.

‘Were they taken away?’

‘The Germans didn’t realise there were Jews here. This area was so poor, so insignificant, supposedly Lutheran, they didn’t bother to check.’

The doors from the kitchen swing open. ‘You should not be speaking about these Jewish things!’ The proprietor screams at me, in Dutch. The cigarette in the corner of her mouth does not move. Eva is writing in her notebook.

‘We were speaking in English,’ I protest.

‘There are no Jews around here now.’

‘Did you know a family by the name of Van Roo. My grandmother and an uncle lived here until the 1980s.’

‘Look in the cemetery.’ Madam hands me an exorbitant bill. Eva offers to pay, but I slam the money on the counter first.

Oma and Opa had a small holding on the outskirts of Groede, a plot of land ending in a triangle fronting the main road. Opa grew all sorts of vegetables and cane fruits which he sold at markets. There was a horse for pulling his cart, and always a pig being fattened. Oma and Opa never ate any part of the pig.

‘Opa’s proudest possession was a gold watch he wore strung across his shirt on a chain, but he had never learnt to tell the time other than by the movements of the sun’

The old people didn’t speak Dutch. They spoke the local Vlaams dialect, interspersed with Yiddish. They lived without electricity and without clocks. Opa’s proudest possession was a gold watch he wore strung across his shirt on a chain, but he had never learnt to tell the time other than by the movements of the sun. Whenever we visited, he gave me the watch to wind and set to the right time. When I finished, I would announce the time and he would say, ‘Ist niet Wunderlich. Wunderlich.’ Even at a very young age, I knew this wasn’t Dutch or German or Yiddish.

Mother was the eldest of five children. On a day in 1920, when Mother was ten, my grandmother from Middelburg was being driven through Zeeuws Vlaanderen in her black carriage and four horses. She was looking for servants. Her eldest son, Lijnus Hendrikus, was driving the carriage. Father and Tante Katrien were inside with their mother. Grandmother’s cold blue eyes and remorseless Calvinist heart lighted on Mother’s auburn hair and creamy skin as the child played outside her parents’ house. Grandmother persuaded herself that Mother was thirteen at least. She gave Oma and Opa some money and a promise that Mother would be brought up Protestant. Mother remembered Oma and Opa standing by, terrified at the sounds coming from the mouth of the great lady from Middelburg. None of them understood her. They could not tell her they weren’t Protestants. They didn’t really understand what was going on until their daughter was driven away, seated between Father and Katrien. Then Oma began screaming. Opa mounted his ancient horse, but the carriage flew too fast.

All the way to Middelburg, Mother begged to be allowed to go home. Katrien pinched her on the arm every time she cried. Father stroked her other arm. Mother said she arrived in Middelburg black and blue on one side, and pink on the other.

After two weeks, she was allowed to go home to visit her parents. Mother walked the seven kilometres to Vlissingen, caught the ferry, then walked the three kilometres to Groede. Oma fed her as best she could, plied her with a parcel of food to supplement the meagre allowance doled out by Father’s family, and sent her off on the return journey. It didn’t occur to Oma and Opa not to send Mother back. They thought that they were being punished for something.

When Mother came to live in Middelburg, she had had a little schooling, in between helping look after her younger siblings. Father’s family had a huge library, and with his help she educated herself. Strangely, Father’s family didn’t prevent her from reading whatever she liked. She read voraciously for the rest of her life, terrified that this talent might somehow desert her if she didn’t keep it honed.

My parents never spoke of the circumstances under which they eventually married. The only wedding photograph, taken in front of the Oostkerk, shows Mother in a black wedding dress. The rest of the party, both sets of parents, Tante Katrien and father’s three brothers, are also in black. All are staring directly into the camera, excepting Uncle Lijnus. His head is turned to Mother. His mouth slightly open as though he would like to eat her.

The Markt and Stadhuis, Middelburg, 1939 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The Markt and Stadhuis, Middelburg, 1939 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The cemetery is on the other side of the road, the same road that bisected Groede in the past. I am surprised to see it identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. We search for these graves first – two British sailors washed up on the nearby beach in that dreadful year of failed Allied offensives, 1944.

‘My parents never spoke of the circumstances under which they eventually married’

Eva tugs at my elbow and points to the lowering sky. ‘Tell me what we’re looking for.’

‘Van Roo or any combination of that name with others.’ Within minutes, we find the evidence: Mother’s brother, Piet Van Roo, who died without heirs in 1987 – the last of that family. Next to him are more Van Roos, then Risseeuw, Abrahams and, fascinatingly, Salomes. The earliest grave dates from 1780: one Miriam Risseeuw Salome. For the next two centuries, Abrahams married Risseuws and Salomes, until by the end of the 1870s the name becomes Risseeuw-Van Roo. Mother’s youngest brother, who died in 1918, is identified as Jaapie Risseeuw-Van Roo. The deaths after that become simply Van Roo. There are no Salomes or Abrahams after the 1970s.

Mother’s Jewish forebears arrived with or at the same time as the Lutheran settlers of the 1740s. By the time of my grandparents’ birth, all that remained of their Judaism was a mezuzah on the door and an aversion to eating pig meat. Whether a rabbi ever attended the community, I don’t know. There is no evidence of a synagogue. The Lutherans who also lived in Groede do not seem to have intermarried with their Jewish neighbours. They do not seem to have survived them, either.

Mother was the only one from her family to end up in a concentration camp. One of the ongoing arguments between my parents consisted of Mother screaming: ‘While you were playing at being a hero, I was in hiding!’ Early on in the war, Mother hid with her family in Groede. She left them, fearful that her presence would endanger the whole community. She hid in various farms belonging to Father’s family until she was betrayed in 1942. Father’s brother, Lijnus Hendrikus, gave Mother to the Nazis. He led them to her, telling them she was the wife of the famous Resistance leader. He stopped short of telling them she was a Jew. Mother spent the rest of the war in Dachau among political prisoners, terrified that the Germans would find out she was a Jew.

There was great lawlessness in the Netherlands after the liberation: summary executions, people mischievously denouncing their neighbours as Nazi sympathisers. Father had an Alsatian dog, a beautiful animal. The poor creature disappeared one day. He was found hung; first he had been disembowelled.

‘There was great lawlessness in the Netherlands after the liberation: summary executions, people mischievously denouncing their neighbours as Nazi sympathisers’

Uncle Lijnus was murdered in the early days of the liberation by a bullet to the back of the head. The Americans who were in charge of Middelburg came to see Father and asked to see his gun. Father said he had lost his gun on one of his last missions before the end of the war. Father had been decorated by Queen Wilhelmina and acclaimed by Prince Bernhard as a war hero. The matter of Uncle Lijnus’s death was not mentioned again. The only evidence that he lived at all was that gold plaque on the pew in the Oostkerk in Middelburg, which Grandfather fondled every Sunday.

I was very young when I absorbed the fact that my father had executed his brother. I didn’t learn it directly, rather from the silences that spoke volumes.

Middleburg after the bombing, May 1940 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Middleburg after the bombing, May 1940 (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

‘It’s going to snow. I think I’ll go on to Bruges,’ Eva says. I hadn’t wanted her company, but now that she’s leaving I think I’ll miss her. The bus stop is opposite the cemetery. Behind is a newly renovated house, next to that a municipal garden ending in a triangle. ‘That’s Oma and Opa’s house!’ I shout.

The bus from Breskens arrives. As Eva is about to board, I ask her: ‘Have you read Brecht’s An Die Nachgeborenen?’ She rolls her eyes.

‘Truly, I live in dark times etc etc.’

‘The last stanza reads: “You, who will emerge from the flood / In which we drowned / Think / Of us …” Brecht ends: Mit Nachsicht. He means looking back with all the weight of history. The past isn’t a different country for Brecht. There’s no way to say “the past” in German or Dutch.’ I yell after the departing bus. Eva, smiling and waving, disappears from my story, no doubt to write her own. Perhaps I’ll recognise her from a photograph on the back of a book one day.

I wander around the outside of Oma and Opa’s house. Of their land, the lovely trees, the cane fruit that hung fat with blossoms every spring, nothing remains. The local council has transformed Opa’s plot into neat concrete rows. Stupid tulips will appear in due course.

I have missed the last bus to Breskens. Never mind, I tell myself, the walk is only a couple of kilometres. In the gloom of a failing afternoon, the landscape is desolate.

The high point, the glory years of Father’s life, were the war years. He said, not long before he died, that everything that came after felt flat.

But he had one more chance to be a hero. After the war, the dykes that the Allies and the Resistance had blown up for the final push into the Netherlands were patched and roughly rebuilt, destined to be rebuilt at a later date. The Netherlands looked to the reclamation of the Zuider Zee in the North as the major postwar project. Father was one of the chief engineers in charge of the maintenance of the dykes around Zeeland. Part of his job was to beg the government in The Hague for money. Very little was made available. Patching on patching was how he described it.

On 31 January 1953 a great storm surge in the Atlantic combined with the highest tides in living memory. Relentless winds hit the coast of England, flooding the Fen country and killing three hundred people. We heard the news on the radio. ‘This is the BBC World Service ...’ I can still mimic those crisp, sharp words. The Dutch translation followed the English version. Father’s face paled as he stood crouched over the radio to extract every comma, every full stop.

‘It’s all right, Papa,’ I hear my child’s voice say. ‘That’s England.’

Father turned around slowly. ‘Child, the water has to come back.’ He fetched his parents from across the road and ordered all of us to the attics at the top of our house. Then he disappeared on his motorbike to the dykes.

Mother and Grandmother spent the rest of the day ferrying valuables to the top of the house. Daylight poured through the roof, where it had not yet been properly repaired after the war. We sat on piles of Persian carpets surrounded by oil paintings – one of them a Rembrandt – while daylight poured through the roof. For once, Mother and Grandmother were speaking to each other. They were unconcerned about any danger to us. Middelburg was the highest point in Walcheren, and we lived in the epicentre of the city. Grandfather fixed up a coke heater and got the crystal radio working. He had used it during the war to listen to Queen Wilhelmina’s broadcasts from England.

By eight o’clock that night the storm out at sea abated to be replaced by a star filled night.

‘This is ridiculous,’ Mother said. ‘I’m going downstairs to sleep in my own bed.’

I begged her to stay in the attic. ‘Papa told us to stay here, remember.’

‘Always playing the hero,’ she grumbled. But she fell asleep on a pile of cushions and carpets. Grandmother, dressed in her long black dress and white coif, lay down next to her. Grandfather and I stayed awake listening to the radio. When the electricity died at nine p.m, we switched to the crystal radio. Through the window in the attic we could not see a single light anywhere in or around Middelburg.

‘This is Radio Hilversum. All residents of Zeeland are warned to move to high ground. This warning applies particularly to the islands of Tholen, St Philips and Walcheren.’ Grandfather’s hand reached for mine – the only time he ever made an affectionate gesture toward me. We lived in the flattest province of a flat country. There was no high ground for anyone to go to.

In the past, church bells rang to summon the populace in times of danger. The high towers in many villages had saved thousands of lives over the centuries. The Germans had taken the church bells during the war. Few had been replaced. Unless one had a crystal radio, there was no way to hear the warnings. The newfangled machines produced at the Phillips factory in Eindhoven required electricity. Radio Hilversum and the BBC kept on sounding the warning to move to higher ground, into an ether where few people could hear.

‘In the past, church bells rang to summon the populace in times of danger. The high towers in many villages had saved thousands of lives over the centuries. The Germans had taken the church bells during the war’

At eleven o’clock, soft singing rose in the distance. Grandfather hugged me tightly. Mother and Grandmother slept on. The singing turned to yowling. Mother woke when the house started to shake. The last word we heard on the crystal radio before that too died was ‘typhoon’. We were buffeted by winds so strong that some of the houses in the Singel Straat collapsed. The wind screamed and screamed. At midnight it dropped, followed by a profound silence. Then we heard the dykes of Walcheren break, one by one.

Father had somehow managed to find air raid sirens. For the rest of that night, the sirens pealed as Zeeland disappeared under waves more relentless than all the armies that had ever invaded us.

At dawn we looked out of the attic window. Middelburg had more or less survived, but beyond the city there was nothing but water, with an occasional chimney protruding.

‘Now I know there is no God,’ Mother said.

The toll for that night was eighteen hundred lives, half a million head of cattle and the loss of all arable farming land recovered since the war. The hundreds (thousands, I suspect) who died in the next few months, like my father’s parents, of influenza, pneumonia and broken hearts were not included in the statistics.

Father was decorated again for his work saving lives that night and for the subsequent reconstruction of the dykes. He took no joy in this. He railed against the government, blaming them for not rebuilding the dykes properly after the war. Eventually, he lost his job and moved to Australia, a bitter, broken man. He died two years after his arrival. My last memories of him are of surly silences punctuated by gin and cigar smoke. The handsome hero of the war died long before he left the Netherlands.

After his death, Mother should have returned home. She struggled with English, didn’t qualify for an Australian widow’s pension, because we were not citizens, and she was over fifty. If we had returned to the Netherlands after Father died, she would have been given a comfortable pension. Instead, she returned to what she had been in the first place – a servant – cleaning toilets and picking up after the well-heeled of Toorak and South Yarra. One day, one of the ladies she worked for ripped a designer dress. Mother offered to fix it and so began another part of her life, mending and dressmaking. In the school holidays, I was co-opted to unpick seams and sew on buttons.

I nagged her to go home. The longer we stayed, the further the possibility of a Dutch education receded. Her only reply ever was that Europe was finished. The Cold War convinced Mother that the dark times were returning – if they had ever left.

Each week, Mother wrote dutiful letters to her parents in Groede, which were read to them by someone in the village. Letters came back: ‘Your mother says ... your father says …’ Eight years after we arrived in Australia, Mother had saved enough money to return home for a holiday. Back in Australia, she wept for days. Still she refused to go home. I was at university by then, independent. I urged her to return, promising that I would follow later. She visited her parents again in 1971, just before Opa died. She consoled herself that she had seen him at least once more before he died. She continued writing weekly letters to Oma, but the answers became more and more sporadic.

Elisabeth Holdsworth as a child (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Elisabeth Holdsworth as a child (photograph courtesy of Elisabeth Holdsworth)

In an act of final revenge from the God she had long ago stopped believing in, Mother was killed in a car accident in 1975. The only divine mercy was that she died instantly.

I rang the village pub in Groede and tried to explain who I was. Asking them to fetch Oma. ‘Moeder is dood. Moeder is dood.’ I said into an uncomprehending silence. Finally, someone must have taken pity on the old lady and told her. I heard a wailing Got! Got! then the phone was cut off.

I sent letters to Oma but received no reply. Six years later, the Dutch embassy informed me that Oma had died intestate. I was her sole beneficiary. After Dutch death duties of sixty per cent, I received some three hundred dollars.

The Rue de Commerce, headquarters of the Zeeuws Resistance during the war, is stifling. The heating has been turned on high to thwart the coming winter. As I switch on the television for company, I see that the Dutch Broadcasting Authority has relented: the rededication of Dresden Cathedral is to be shown on television. Overblown singing from the weddingcake cathedral bellows into my room. On another channel there is a documentary about the Dutch coach who will guide the Australian Socceroos into the World Cup.

The Volkskrant has been left in my room. Opposition is rising in the Netherlands to the repressive imigration policies of the present government. In a front-page editorial, my childhood friend, Fritz, now an independent member of parliament, thunders that this is not what our parents fought the war for. Of the group Mother called the Nachgeborenen, Fritz and I are the only ones still alive. Like me, Fritz has developed a close association with a cardiologist.

I turn the television off to gaze outside the hotel room window at the floodlit panorama of the Middelburg Stadhuis through a curtain of snow. The part of me that carries the steely resolve of my Calvinist ancestors warns me not to weep.

Father’s sister, Tante Katrien, died in 2005 at the age of one hundred and five, still on active service to the House of Orange. She left me her titles and worldly goods, including the black pearls and boxes and boxes of memorabilia from eighty-five years of service to the royal family. In her will, Katrien referred to me, as she had always done, as het kind; the Nachgeborenen who wasn’t supposed to survive, much less to sing the songs of the past.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.