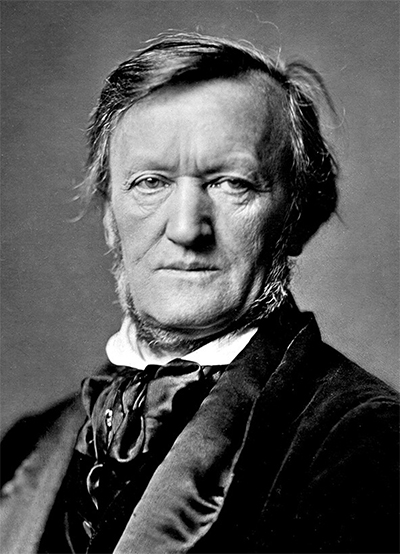

Who’s Afraid of Richard Wagner?

Passions have always run high in the Wagner dynasty. Richard, the patriarch, waged a lifelong battle to impose his vision of a purified German art – freed of decadent foreign influences – on a sceptical, at times overtly hostile, culture. His great-grandson Gottfried, who bears a striking physical resemblance to his forebear, is equally dedicated to his mission in life: to alert the world to the intrinsic evil and pernicious influence of Wagner’s works. The cost has been considerable. As he recounts in his obsessive autobiography, The Wagner Legacy (Sanctuary Publishing, 1998 and 2000), he has been disowned by his father, Wolfgang (who has been sole Director of the Bayreuth Festival since 1966), reviled by Wagner enthusiasts in Europe and America, denied every opportunity of working in theatres and opera houses, slandered and even hounded, on occasions, by death threats. Yet, in circumstances where others might have been tempted to throw in the towel, he continues to roam the world, delivering lectures, participating in seminars and discussion- groups with a single-minded aim – to atone for the great evil his family unleashed from their stronghold in the pleasant, nondescript little town of Bayreuth, where the faithful gather each summer to worship the Master, and perhaps to remember the Master’s greatest disciple, the Führer, the intimate friend of Winifred Wagner, Gottfried’s grandmother.

Such views are by no means uncommon: they have been aired often enough in the last fifty years. Where Gottfried Wagner departs from the norm, or at least from received wisdom, is in his uncompromising condemnation of what came to be known as the ‘New Bayreuth’. When the Festival reopened in 1951 – after the theatre had been desecrated by variety shows for US army personnel – the composer’s grandsons (Wieland, who died in 1966, and Wolfgang, Gottfried’s father) allegedly set out to strip their grandfather’s work of extraneous ideological trappings, those celebrations of Teutonic might and superiority which directors and designers conveyed by means of winged helmets, heroic posturings, and yards and yards of braided golden hair. According to Gottfried Wagner, however, altering the staging of the music dramas, so as to highlight their abstract and symbolic nature, was only window-dressing. The old attitudes and obsessions survived, as they remained fundamentally unchanged in later years when his father invited such left-wing directors as Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer, as well as Jewish musicians (most notably James Levine and Daniel Barenboim), to work at Bayreuth. In short, the new spirit on the ‘Green Hill’ is no more than a cynical exercise in tokenism and in the manipulation of public opinion.Dr Wagner’s sincerity is beyond question, but the intensity of his dedication to his cause can prove unsettling. I met him in Sydney in June 2001 at a seminar on Wagner’s politics organised by a Jewish cultural group. What he had to say on that afternoon was familiar enough, encapsulated by a comment that runs through the text of The Wagner Legacy: the road from Bayreuth to Auschwitz is direct and clearly signposted. He rehearsed the often recounted details of his relatives’ misdeeds: his great-grandparents’ ingrained anti-Semitism, reflected in Wagner’s stage works as much as in his ranting tracts and pamphlets; the dalliance between Winifred Wagner and Hitler; Winifred’s dedication to the memory of ‘USA’ (unser seliger Adolf; our blessed Adolf) in the years after the collapse of the Third Reich.

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus auditorium

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus auditorium

Most of the audience at that seminar seemed, understandably, pleased by what Dr Wagner had to say, particularly by his unqualified support for the unofficial ban on his great-grandfather’s music which has been in force in Israel for half a century or more. Yet I noticed one or two people expressing misgivings and some discomfort. They seemed to be elderly Central Europeans, people who probably came to Australia as youngish adults after World War II. It struck me that they may have well brought with them something of the widespread adulation of Wagner among urban European Jewry in the first half or so of the twentieth century, which they had inherited, perhaps, from their parents and grandparents. The frequently secular and assimilated Jews of that generation –

my father’s family among them – must have known about the vile racist doctrines nurtured in Bayreuth during their lifetime, yet the knowledge left them indifferent, it seems, where the glories of Wagner’s music were concerned.

That is a conundrum which Gottfried Wagner addresses, with oblique tact, in his lectures and in his autobiography. To this day, he remarks, some of his most fervent antagonists, those who are determined to block his career as an opera director, are Jews – Daniel Barenboim’s name crops up several times in The Wagner Legacy. What he does not say is something that has been said by others on many occasions: the cult of Wagner among European Jews was a sign of the folly (or worse) of people who turned their backs on their heritage and its traditions and attempted to merge into the gentile world.

Daniel Barenboim performing at the Teatro Colón in 2015 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Daniel Barenboim performing at the Teatro Colón in 2015 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Some contemporary Jews are deeply troubled by that anomaly – a rabbi called Julia Neuberger, for instance, who contributed a preface to the revised translation of Gottfried Wagner’s autobiography. ‘Many Jews,’ she wrote, ‘remain Wagnerians – indeed my own grandfather was a keen enthusiast. Is it that they refuse to see? Or are they – as I am sometimes myself – so carried away by the animal appeal of the music that they will forgive its creator anything?’

Others, including my father if he were alive, would, I suspect, put it rather differently. Forgiving the creator is not the question; rather, what is at stake is the acknowledgment that the intentions and personality of the artist have little bearing in the long run on works of art. On that topic, as on most others, Gottfried Wagner seems to hold uncompromising attitudes. The distinction between Wagner the man and Wagner the artist will not hold, he insists. Apart from anything else, there are the texts, the libretti, to consider – and these, he continues, together with certain musical characteristics, reveal unambiguous evidence of ideological contamination.

He mentions (as many others have in the past) the allegedly Jewish cadences of the music Wagner wrote for the grasping, treacherous Mime of The Ring. He reminds his readers and listeners that Beckmesser, the arriviste town clerk of The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, is a caricature of the celebrated Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick, a Jew. The most telling evidence he offers, however, is Wagner’s last work, the ‘Sacred Festival Stage Play’ Parsifal, which will be performed in Adelaide later this month.

With that work, Gottfried Wagner argues, his great-grandfather’s theoretical obsessions reached a particularly objectionable culmination. Many would agree heartily: despite its innovative musical language – which exerted remarkable influence over the music of the first half of the twentieth century – and magnificent choral writing, and despite several highly striking and effective episodes, Parsifal breathes a cloying religioso air, a sentimental coyness about sexuality and the erotic, all of which render it, even in the eyes of some fervent Wagnerites, a disappointing conclusion to a remarkable career. The Wagner family’s endeavours, especially those of the composer’s widow, Cosima, to bolster the work’s mystique by their attempts to retain exclusive performance rights for the Bayreuth Festival (which Cosima succeeded in ensuring until 1913) and such childish rituals as discouraging applause during performances of the work, particularly after the first act, seem only to highlight the shortcomings of this misguided essay in marrying opera with pseudo-ecclesiastical rites.

For Gottfried Wagner, however, such aesthetic flaws are rendered insignificant by the pernicious racial and cultural doctrines Parsifal promotes and embodies. This long, static fable of how the community of the Holy Grail was restored by ‘the pure fool’ Parsifal, how the evil of Klingsor, the selfcastrated fallen knight, came to be annulled, and how Kundry, the wild woman who had laughed in the face of Christ as he suffered on the Cross, found redemption reveals for him unambiguous evidence of his great-grandfather’s anti-Semitic fury, a determination to Aryanise Christ and to locate moral, ethical and cultural health in a typically Germanic notion of brotherhood – of the kind that led to the formation of the SS.

The clincher, he always insists, as he did on that Sunday afternoon when his voice rose higher and higher and as his clenched fist pounded the lectern, is the absence of Jews from Wagner’s dramatis personae or indeed his failure to refer to Jews anywhere in his libretti. The argument is tortuous and somewhat unconvincing. Why should the absence of Jews indicate deeply ingrained anti-Semitism? Might it not suggest, indeed, that the composer-poet’s imagination was rather more subtle and humane than his theoretical and political diatribes? But Dr Wagner will have none of that. For him, the absence itself is the most powerful confirmation. So, in his autobiography, he takes his father to task for departing in his most recent production of Parsifal from Wagner’s explicit stage directions for the conclusion of the opera. Wagner called for Kundry’s death after she had achieved forgiveness and redemption, because (his great-grandson implies) even a redeemed (that is to say, perhaps, converted) Jew must not be accepted into the newly forged community of holiness and cultural health. Wolfgang Wagner, in order to mask his own complicity in the persistence of Nazism in contemporary Germany, his son suggests, made the tiny adjustment of allowing Kundry to survive so as to disarm his critics and to permit him to continue in his fundamentally unregenerate ways.

Such attitudes and preoccupations reveal a characteristically European, indeed specifically German, cast of mind. The seriousness with which Gottfried Wagner approaches his great-grandfather’s works and their influence betokens a respect for culture and a recognition of its potency to influence large-scale political and social phenomena which other societies might do well to emulate. Yet, as I left that intense and emotion-charged seminar, a sceptical imp somewhere in my mind kept insisting that all this was to place too high an importance on what are, when all is said and done, merely striking, at times magnificent, at others tedious and bombastic, operas. That Wagner provided a model and an inspiration for those who committed a great outrage is undeniable. Yet many roads besides the one from Bayreuth led to Auschwitz and Treblinka, Belsen and Theresienstadt – and some of them were far broader, and better paved.

And that, in turn, suggested something else. Gottfried Wagner will not accept the proposition that works of the imagination may transcend the intentions of their creators or the uses to which they are put by the unscrupulous or the exploitative. Yet the history of culture reveals many instances where precisely that has happened. Who, for instance, now thinks of Macbeth as agitprop for Stuart legitimacy? Time and the fundamental ambiguity of works of art – as opposed to the ambitions of mere propaganda – usually ensure that even the most ideologically driven novel, poem, play or musical work can transform itself into something rich and strange, and far removed from its creator’s overt intentions.

Richard Wagner in 1871 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Richard Wagner in 1871 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Has that happened with Wagner? I think it has, and I think furthermore that the process started long ago, when cultivated Europeans – many of them Jews – recognised that, for all their bombast and tedium, Wagner’s works are the products of an extraordinary musical and dramatic imagination that achieved far more than the animal appeal Rabbi Neuberger mentioned in her preface to The Wagner Legacy. I am sure that my grandparents – who had the good fortune to hear Mahler conduct Wagner in Budapest and Vienna – could not forgive Wagner for his appalling ideals. But their cultural confidence, or sophistication if you like, ensured that they recognised a distinction which seems far more difficult to draw in the contemporary cultural and political climate.

That is hardly surprising, in one way: my grandparents’ generation did not, at the time, know about the road to Auschwitz. We, in our time, do not possess that privilege. Yet we should be on our guard against fulfilling, in an oblique albeit significant way, the ambitions of Wagner the ideologue and of all those who embraced with enthusiasm his pernicious theories of racial purity. Gottfried Wagner, for understandable reasons, demonises his great-grandfather and his works. That, to my mind, is merely the reverse-side of adulation. Away from the hothouse cultural atmosphere of Europe, particularly the endless internecine disputes of the Wagner clan, more moderate and civilised attitudes may flourish.

They flourished, for me at least, three years ago when The Ring came to Adelaide in a restrained and elegant production from Paris. In a place and a culture far removed from the obsessions of Bayreuth, the tetralogy disclosed itself as a great, though inevitably flawed, work, arguably the nineteenth century’s most notable cultural monument. Something similar will happen, I hope, when Parsifal (a lesser, though still striking, achievement) is performed there. And if the audience should decide to clap after the first act – as a few people did in Bayreuth in 1995 when the great Plácido Domingo sang the title role – we will not have to endure (I trust) the furious hissing which accompanied that infringement of the silliest of the many silly rituals of the Green Hill.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.