Letters to the Editor - October 2001

Jazzing it up

Dear Editor,

Patrick Wolfe’s review of my book The Culture Cult (‘The Remorseless Right’, ABR, September 2001) makes an exciting read (such astonishing political intrigues!), but the truth is not quite what he imagines. Let me clarify a few points.

I am said to have made ‘scurrilous personal attacks’ on Raymond Williams, a man who is dead and unable to respond, something which is ‘truly shameful’. The original essay discussing Williams appeared in Encounter twenty years ago. Although Williams was still with us then, I don’t recall him writing a response. In any case, when I updated the essay recently, the worst charges against him (involving what I think we may fairly call his ‘truly shameful’ apologia for the Khmer Rouge) were taken from Fred Inglis’s recent biography. Inglis, an admirer of Williams, frankly expresses his own disgust at Williams’s defence of ‘the killing fields’. Which must make Williams’s biographer at least as shameful as me.

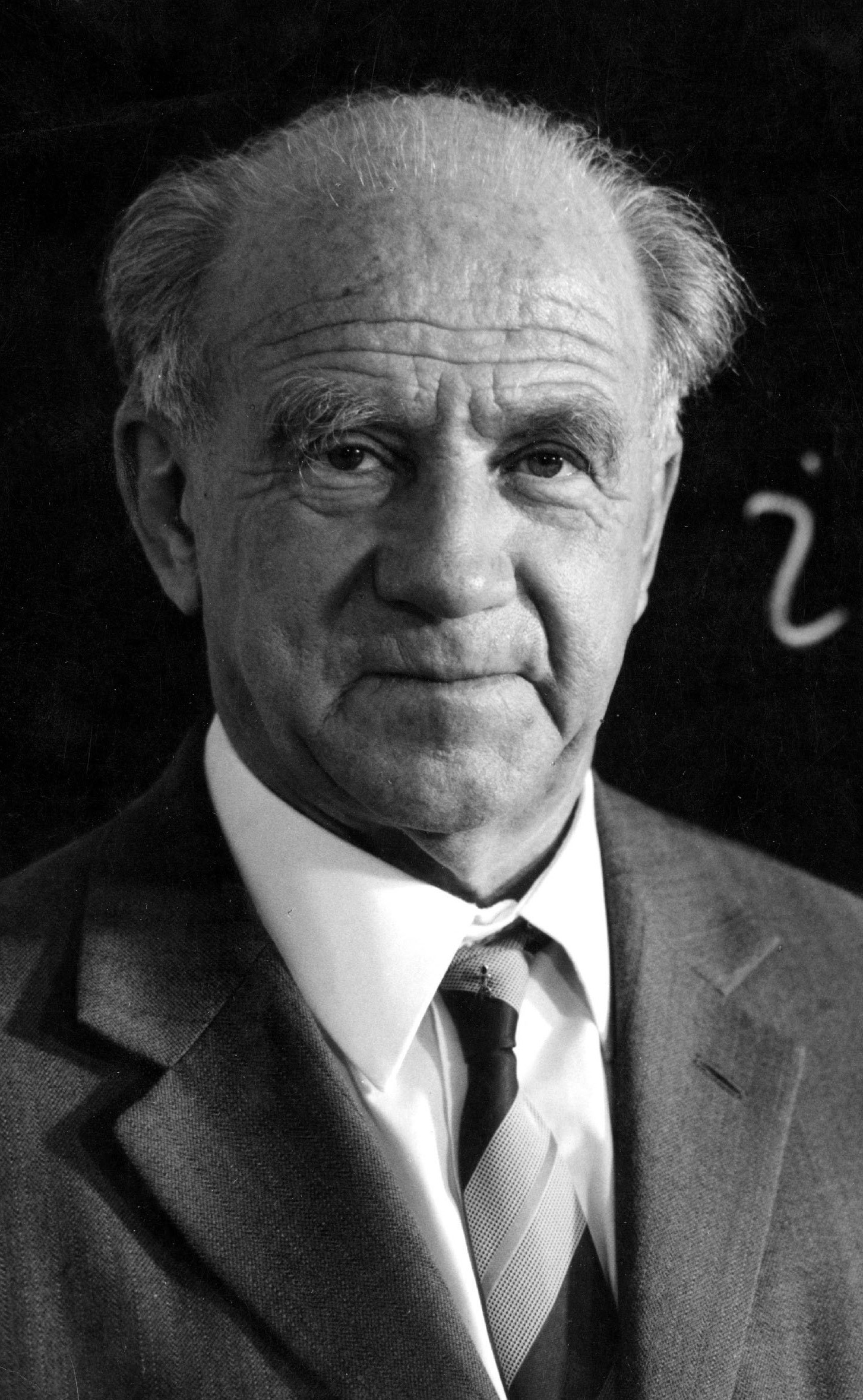

I am accused of not reading the texts I comment on. Odd though it might seem, given Isaiah Berlin’s loquacity, I have certainly read what he has to say about tribalism and nationalism, and that’s where I found Herder’s resentful provincial rage against Paris for not giving him the respect he felt he was due. Ample references are provided in my book for anyone who wants to follow up the matter. This is not a ‘bohemian theory’ (Wolfe’s curious description) but the explanation offered by Berlin himself. As for Ernest Gellner, my quotation from this author occurs in the course of expounding his interpretation of Wittgenstein in Language and Solitude. Gellner’s fascinating commentary on the communalist/individualist divide, under the rubric of ‘The Habsburg Dilemma’, is my main subject – not Wittgenstein’s thought, the intricacies of which I don’t pretend to grasp. Gellner himself wrote an awful lot, and I’m familiar with some of it, but his discussion of Wittgenstein and Vienna is my exclusive concern here. If Wolfe wants to be regarded as a serious critic of this sort of thing, he will have to think a lot harder and apply his mind much more closely to the text. I wish him well.

It is suggested that I ‘[blame] the Aborigines’ for romancing their own past. Not at all. I blame a whole army of deluded, middleclass whites who have a heavy emotional and political investment in idealising the primitive world. It’s time they moved on. Their urban sentimentalism, widely promoted in universities and by the media, derives directly from Rousseau.

I am accused of behaving badly in distancing myself from professional colleagues in anthropology, and declining to turn up at a conference hate session specially devoted to my book. Your readers should know that, although I made a few documentaries thirty-five years ago, I have no serious credentials in anthropology, have never claimed to be an anthropologist, have no wish to be regarded as an anthropologist, and have not been to an academic conference of any kind in over twenty years. The prospect of this provincial talkfest seemed every bit as repellent as its predecessors. In any case, the book is not primarily about anthropology. It is about a disease of the Western imagination: the reactionary infatuation with the tribal and communal that feeds the hatred of modernity so conspicuous today. A recent episode in New York shows the extremes to which this hatred can all too easily lead.

Finally, Wolfe implies that The Culture Cult has woeful shortcomings as an academic publication. To this, I plead guilty as charged. This is because it is not an academic book, the American publisher having accepted it on the explicit condition that it be written for the general reader. So I jazzed it up a bit and added enough entertainment to help someone trying to cope with it on a train. Of course, it uses academic writing for its argument, but the argument itself is a good-natured satire on human folly: a satire to which your reviewer seems entirely blind. Might I suggest that curious readers obtain a copy and see for themselves?

Roger Sandall, Bondi Beach, NSW

Our Shakespearean past

Dear Editor,

Peter Craven’s ‘Shakespeare in Australia’ in ABR (September 2001) styles itself ‘a cartoon of a bygone history’. The zing of his essay certainly derives from its heady succession of vivid vignettes and quirky accentuations, and his approach will prod us – more effectively than any dogged survey – into assembling our own tableaux of remembered highlights from our Shakespearean past.

Particular favourites of mine, not noted by Craven, are Rex Cramphorn’s staging of The Tempest in 1972–73 and Jane Adamson’s book-length critical studies, Othello As Tragedy (1980) and Troilus and Cressida (1987).

Cramphorn’s incantatory, percussive Tempest is still something of a legend – on a par, in Australian theatrical circles at least, with Peter Brook’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to which Craven pays due homage. Adamson’s work has tended to be overshadowed by more recent developments in Shakespearean criticism (some of which seem brazenly indifferent to how the plays work as literature or even as theatre) and also by the reputation of her late husband Sam Goldberg’s book on King Lear (1974).

Craven unequivocally nominates Goldberg’s book ‘the finest criticism I have read of Shakespeare by an Australian’. Yet he also suggests its want of ‘essayistic colour’ – ironic for a book that calls itself An Essay on King Lear, and doubly ironic in that Craven has made himself such a doughty champion of the essay form in this country. Adamson’s work has all the terse elegance of the most incisive essayists, yet it is also capable of blossoming forth in such rich and resonant passages as this gloss on Othello’s dying words: ‘For the last time, reality seems cushioned by voluptuous assonance, seduced, softened and recomposed in statically picturesque images, tamed by the art of a lingering cadence.’

Ian Britain, Meanjin, Carlton, Vic.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.