Colonialism

This week, on the ABR podcast, we feature a special conversation between author and journalist David Marr, historian Mark McKenna and ABR’s Georgina Arnott, recorded in the middle of September 2023, one month out from the Voice referendum. The subject was David Marr’s new book, Killing for Country: A family story, which takes the reader to early nineteenth-century New South Wales and follows the bloodshed of invasion as it tracks north. Mark McKenna’s review of Killing for Country is published in the October issue of ABR.

... (read more)Empire, Incorporated: The corporations that built British colonialism by Philip J. Stern

by Clinton Fernandes •

Barron Field in New South Wales: The poetics of Terra Nullius by Justin Clemens and Thomas H. Ford

by Philip Mead •

The Lives and Legacies of a Carceral Island: A biographical history of Wadjemup/Rottnest Island by Ann Curthoys, Shino Konishi, and Alexandra Ludewig

by Georgina Arnott •

The Queen is Dead: The time has come for a reckoning by Stan Grant

by Malcolm Allbrook •

O'Leary of the Underworld: The untold story of the Forrest River Massacre by Kate Auty

by Ann Curthoys •

Apartheid in Shakespeare and other reflections by Sibnarayan Ray

by Clement Semmler •

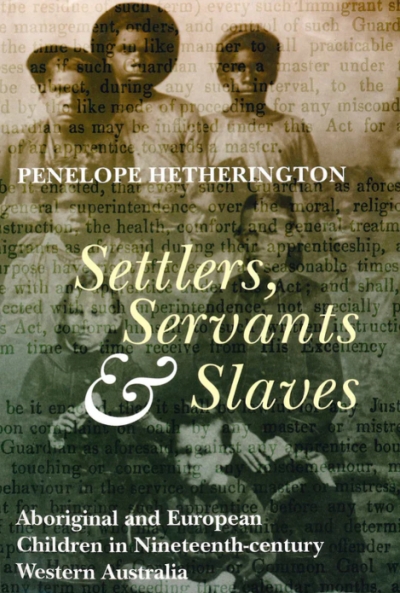

Settlers, Servants & Slaves: Aboriginal and European children in nineteenth-century Western Australia by Penelope Hetherington

by Peggy Brock •

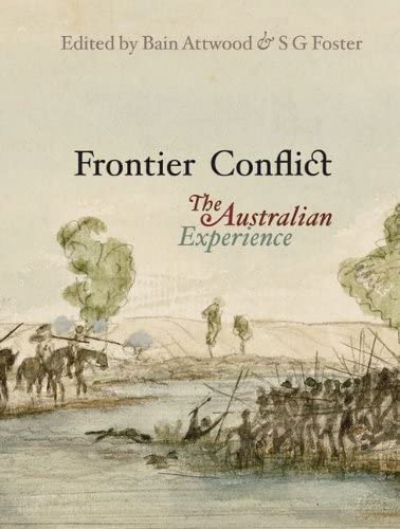

Frontier Conflict: The Australian experience edited by Bain Attwood and S.G. Foster

by John Connor •