Biography

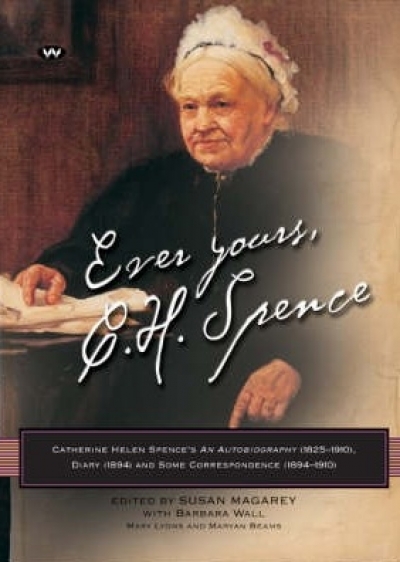

Ever Yours, C.H. Spence: Catherine Helen Spence’s an autobiography (1825–1910), diary (1894) and some correspondence (1894–1910) edited by Susan Magarey

by Elizabeth Webby •

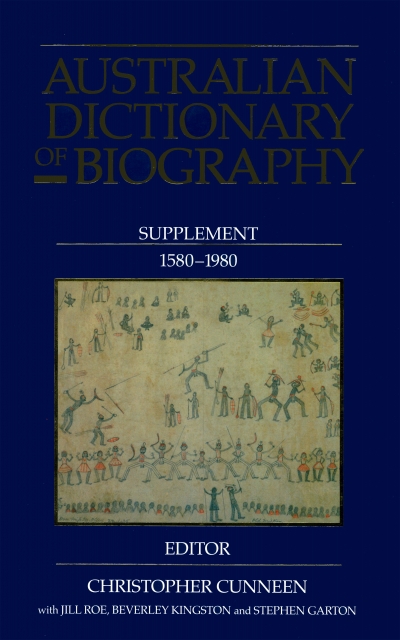

Australian Dictionary of Biography: Supplement, 1580–1980 by Christopher Cunneen

by Paul Brunton •

The Last Explorer: Hubert Wilkins, Australia's unknown hero by Simon Nasht

by Paul de Serville •

Margaret Olley: Far from a still life by Meg Stewart

by Brenda Niall •

The Life of George Bass: Surgeon and sailor of the enlightenment by Miriam Estensen

by Gillian Dooley •

A City Lost and Found: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne by Robyn Annear

by Ian Morrison •

T.W. Edgeworth David: A life by David Branagan

by John Thompson •

The Tyrannicide Brief: The story of the man who sent Charles I to the scaffold by Geoffrey Robertson

by John Button •