'Ti amo ?'

Desmond O’Grady has worked in Rome since 1962 as a freelance writer. In this month’s Telecom Australian Voices essay, he writes about the diverse relationships between Italy and Australia and how changing countries affects writers, migrants and ideas.

I was supercilious towards Italy and Italians before seeing Italian films and reading Curzio Malaparte’s novels. Malaparte foiled the superciliousness while the films’ backgrounds, something as simple as sunlight in the squares, intrigued. Previously France had provided an alternative to Anglo-Saxon culture. An Irish heritage set me askew to Anglo-Saxondom, but it did not give me another language as English had supplanted Gaelic. In any case, Ireland was the past and a somewhat mythic past at that. My parents were attached to Ireland but even their parents had been born in Australia. Indeed there had been no direct contact with Ireland since the mid-nineteenth century; it was the past you could not reach but only romanticise. Being of Irish origin meant being Catholic outside the Anglo-Protestant Pale.

Prejudices such as that Italians ate revoltingly oily food or that the women inevitably became fat affected my view of Italy. Newsreels of columns of Italian soldiers who had surrendered in North Africa suggested they were a spineless lot. Certainly Australian Catholics looked to Rome but, from what we heard, in that sphere too Italians had let the side down. Admittedly Italians had somehow produced outstanding works of art but that was in the distant past.

In Mosman, in 1940, a schoolmate named Joey Favalaro, son of the local greengrocer, piqued my interest, he was the first Italian I had met. I had not realised that, in a Federation red-brick, red-tiled, leadlighted house called Vesuvio, but one down from ours in Prince Albert Street, lived an Italian. He had arrived in Australia in 1897 and, with what one observer called ‘cheerful despair’, ran an art school whose students included Donald Friend, Roland Wakelin, Roy de Maistre, Grace Cossington-Smith and Arthur Murch. He was Antonio Dattilo Rubbo.

In a class I taught later in Melbourne was an Italian boy from Foggia, which I asked him to locate on a map. As I had already booked to sail for Europe, I gave the class the sop of copying an essay and asked the boy to write something in Italian on the blackboard. I can still recall how utterly alien seemed io sono, tu sei, lei e, which have now become second nature. When I acquired travellers’ cheques before leaving for Italy the bank teller mistakenly said, as if describing a weird deficiency disease, ‘Every word they’ve got ends in i or o or e’.

Naples was simply the first European port-of-call on an intended world trip. I was not trapped in Naples, but in Rome, or perhaps it was while hitchhiking to Rome that it happened. Thumbing a ride outside Naples, I talked to a man seated in front of his house about the Germans’ wartime behaviour. I was impressed by his lack of animosity, his tolerant ‘war is war’ attitude. However, when he spoke against his English mother-inlaw, who was staying with him, he was vehement. He exemplified the Italian immersion in the particular that pleased me.

It was only one of many discoveries which were an antidote to superciliousness (although my initial reaction included an upsurge of chauvinism). Then I met or became interested in others who have moved between the two countries, Australians in Italy, Italians in Australia, Italians who had returned from Australia and those who shuttle between the two countries, mid-Indian Ocean people. Having two countries can induce vertigo. The actress Greta Scacchi, who has three (Italy where she was born, England where she has lived longest and Australia where she has residence, votes, and pays taxes) says ‘I enjoy being a half-caste and gypsy but sometimes it’s confusing. It’s hard to know from which viewpoint to assess things. And wherever you are, there’s always something … missing’.

I became curious about interaction between the two cultures, one Mediterranean, the other basically Anglo-Celtic in a continent with some Mediterranean characteristics whose population equals only that of Italy’s Po Valley. It became clear that the relationship, often considered to consist simply of Italians going to Australia, was instead a two-way traffic which sometimes becomes a circuit. For instance, when, on 26 March 1930, the Bolognese Guglielmo Marconi switched on Sydney Town Hall lights from his ship moored off Genoa, he spurred Australian research in radio communication. This influenced the body that became the radio astronomy unit within the CSIRO. Half a century after Marconi’s experiment, this unit aided the development of radio astronomy at Bologna University.

Aborigines came to Italy in the last century: at least five students, only one of whom returned to Australia, were in ecclesiastical institutions. Anthony Fernando, a campaigner for human rights, believed to be of Aboriginal-Sri Lankan origin, lived for a time in Milan and, in 1921, unsuccessfully tried to see Pope Benedict XV to enlist his support.

Between 1868 and the First World War, the Italian Geographic Society Bulletin carried several brief references to Australian Aborigines. The sources, which were not solely Italian, tended to consider the Aborigines as part of the environment rather than as human beings. Writing in 1903, Giovanni Grasso foresaw the Aborigines would be forced to withdraw progressively into the interior with the only possible sustaining hope that they be reincarnated as whites. (Grasso’s article may be a distant companion piece to John O’Grady’s They’re a Weird Mob, which portrays a Milanese journalist whose aspiration is to become an Ocker.)

Exceptions were a report in 1911, from the Italian Consul in Western Australia, deploring the degradation caused by whites and an accusation, in an item of 1906, that whites had committed crimes against Aborigines. Evidence of this interest is found today in Aboriginal collections, particularly Rome’s Pigorini Ethnographic Museum, in the Florence University Anthropology Museum, in the Denz-Rialto Primitive Art Museum of Rimini and the Vatican Ethnological Museum whose most prized objects are ten decorated funeral poles from Melville Island. It has about two hundred artefacts from the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Most were sent for a huge missionary exhibition held in Rome in 1925.

Needless to say, there have always been strong Italian Australian Catholic links. The archives of the Vatican Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples (formerly Propaganda Fide) contain much of the history of the Catholic Church in Australia. A goodly proportion of Australian Catholic clergy was set firmly in the Roman mould at Propaganda Fide College on the Janiculum hill which looks directly across to the window of the Pope’s study. At the College parapet many future Australian bishops were inspired by a wave of a hand from the Pope’s window. Australians were ringleaders in two student rebellions at the College just before and during the Vatican Council in 1962–65. Australian Catholics’ offerings enabled the building of a new section of the College which was completed only shortly before the bishops decided not to send any more students there.

It was on the steps of Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo church in 1831 that the English Benedictine William Ullathorne was convinced to go to Sydney where he organised the Catholic Church, while in the Vatican during the First World War Daniel Mannix was advised to forget Ireland and knuckle down to pastoral issues in Melbourne. Sister Mary McKillop, who will be Australia’s first saint, pleaded her case against Australian ecclesiastical opponents in Rome and the examples could be multiplied down to the Vatican judgment on B.A. Santamaria’s Movement.

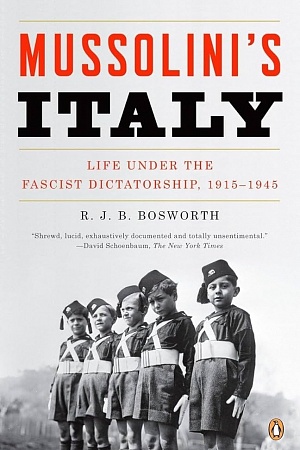

Among pre-war Italian migrants to Australia there were fervent Fascists but also crusading anti-Fascists, such as the Socialist lawyer Omero Schiassi and a group of Jewish refugees, but there were Australian equivalents in Italy: Sydney-sider Herbert Moran, a Rugby international, surgeon and friend of Christopher Brennan, championed Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia while the novelist Doris Sutton-Manners participated in wartime partisan anti-Fascist activities in North Italy.

Just as Australians’ experience of Italy has given them a new perspective on Australia, as seen in A.D. Hope’s ‘A Letter from Rome’, some Italians’ experience in Australia changed perception of their homeland. Francesco Sceusa was more critical of Italian Socialist theory after observing, early this century, pragmatic socialism’s achievements in Australia. Raffaello Carboni saw a parallel between the Eureka Stockade and an antiBourbon uprising in Palermo shortly before Garibaldi occupied the city. To commemorate its victims, he wrote a play about the Palermo uprising, using the same techniques (such as deliberate mythmaking and inclusion of documentary material) as in his The Eureka Stockade. A rhetorical model developed in Ballarat served to frame Sicilian events.

As a young man, Martin Boyd told his father that he wanted to go to Italy, where he was in fact to spend his last seventeen years, to see ‘those marvellous blue skies’. However, Mario Praz observed that Australian skies are more luminous that those that drew to Rome painters such as Poussin.

Martin Boyd’s aspirations may seem to justify Victor Daly’s complaint in ‘Correggio Jones’ that the ideal of Italy as a land of beauty and culture distracted artists from Australian subjects:

Correggio Jones an artist was

Of pure Australian race,

But native subjects scorned because

They were too commonplace.

Correggio (a corruption of Reg?) was alienated:

His body dwells in Gander Flat

His soul’s in Italy.

Jeffrey Smart dwells near Arezzo, but is not bemused by classical subjects. Instead he is agog over Coke crates, autostrada signs and fibro-cement factories which he transforms into icons of modernity. He refers to those painters whose subjects are determined by their nationality as ‘billabong boys’. Smart maintains that it is normal for Australians of European stock to live in Europe: ‘agonising over identity is a steady growth industry but it’s nonsense – our artists can find inspiration both at home and in Italy’.

Ken Whisson, who lives near Perugia, chose Italy for personal as well as artistic reasons. ‘I felt at home for the first time in my life’, he discovered on his first visit. ‘I wasn’t expected to be like everyone else and it wasn’t strange to be a painter.’ He appreciated ‘a particularly Italian talent: the capacity to relate to strangers’.

Sculptor Rod Dudley who comes from what he calls ‘staunchly Methodist’ Glen Iris in Melbourne, lives in Besozzo near Lake Magiore and the Swiss border. He finds Italians ‘see life as very limited’, but nevertheless are ‘admirably hopeful’. As an artist, he points out, he lives in Europe rather than Italy, as he seeks a European market.

Norma Redpath left for Italy in 1956 to flee Melbourne mores and later moved back to escape those of Milan. She reacted against Melburnians who, if creative projects were proposed, asked ‘where’ll that get you?’ The answer was Italy, but, when settled in Milan, she found herself reacting against conformism. ‘By moving between one country and the other as an eternal expatriate, a label I’ve accepted only recently, I escape being suffocated by either society,’ says Redpath, ‘and I maintain equilibrium by awareness of the other country to the one in which I’m living. My sculpture studio, wherever it is, thus remains a constant, neutral creative space.’

One of the first Australian artists to seek a cultural ideal in Italy was Adelaide Ironside. In 1860 in Rome the painter noted that, if Australia had the Italians’ love of the beauty, it would be a second Italy. Ethel Turner always dreamt of a cultural pilgrimage to Italy. In Florence the author of Seven Little Australians found a pensione associated with seven Big Writers: Trollope, the Brownings, George Eliot, Hawthorne, Hardy and Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of Little Lord Fauntleroy. Turner was exploring a cultural source land that had attracted scores of Anglo-American writers before her.

In nineteenth-century Australia there was a cultural elite that knew Italian, admired Italian literature, music, and art, and sympathised with Garibaldi. It introduced Italian books in public libraries and Italian paintings (or copies of them) in public art galleries. The tradition was dented by two world wars and the Depression but, in the 1950s, many Australians sailed for Italy on the ships that had brought migrants to Australia.

The migrants were often ill at ease to find Australia belonged to the English crown but many Australians felt Italy was theirs. They had been introduced to Italy at school and, on arrival found to their delight that there was such continuity of place, feeling and attitude that it was no mere museum. Even the climate was somewhat familiar; certainly the gum trees were. As the first stay on Grand Tour, Italy stood for Europe. It enabled Australians, as the historian Roslyn Pesman Cooper has noted, to claim their European heritage without the Imperial midwife.

In Italy, or the idea of Italy, some Australians sought their passionate true selves while many Italians in Australia passionately sought a job. If not tourists, the Australians were, in R.L. Stevenson’s terms, ‘amateur migrants’, not motivated by economic necessity. They were seeking something different from what they had known since birth whereas many Italian migrants sought, instead, the means to obtain more of the same. Except for those who left zones consigned to Yugoslavia after the Second World War, Italians migrated mainly for economic reasons which made them more like the Dutch than Eastern European political refugees or even those Greeks who fled the colonels’ regime. They had moved from one democracy to another and could return home, as one in five did, as soon as they had the fare. As their culture was not threatened in their homeland, they were not obsessive about conserving it.

Postwar migration to Australia differed from that to the United States of America early in the century because, from 1951, it was backed by a government-to-government agreement, employment was readily available, and work conditions were strictly regulated. As migrants were protected by governments rather than godfathers, the impact of changing countries was less traumatic than it had been in the United States.

The result has been an apparently satisfied group whose influence is less than its numbers might suggest. Or, at least, it is a diffuse influence as Italians lack a national representative body such as the Jews and Ukrainians have. Moreover, although most are Catholic, they are not members of a national church such as the Greek Orthodox, which can have a representative function. The way the Italians are organised, or disorganised, in Australia somewhat resembles society in Italy itself. It seems as if everyone, or every subgroup, is pulling in different directions but there is an underlying unity and often the results are surprisingly positive. Unlike Chinese in Australia, Italians (except for a small proportion from Argentina and Egypt) share a common source country. Unlike Yugoslavs, they share a common language and it finds expression in their press. And, in contrast to Lebanese, they have a common religious background. Despite their seeming lack of cohesion, they have been effective on the issues that most concern them: pension portability and language maintenance. Half of the money spent on community language teaching in Australia goes to Italian.

As the community has not been replenished from Italy since the early 1970s, within a decade most Italianborn members will have retired. Italo-Australians will then have to ensure the continuance of Italian influence in public life; the American experience suggests it will last long after the migrant phase.

Large-scale Italian migration to Australia was circumscribed to the quarter century beginning in 1947. In 1952 alone over thirty thousand arrived. Australia was the last chapter in the saga of European emigration which, in the century’s first decade, saw more than two million sail to the United States, a million to Argentina, but only seven thousand to Australia. Following the postwar migration surge, it is estimated that almost a million Australians have some Italian blood. By the late 1980s, however, twice as many Italians were returning from Australia migrating here.

Those of Italian descent who had become thoroughly Australian found Italians of the post-war influx quite exotic. Some of the newcomers were surprised to find many coreligionists in Australia, but still more surprised to see how they lived their faith. The delusion was mutual. For Catholics of Irish origin, it was the Mass that mattered. For Italians, particularly those from rural zones, it was the festa, which included the mass, that mattered, as it dramatised religion’s social-celebratory aspect. In the Mass, Australian Catholics reaffirmed their beliefs; in the festa, Italians reaffirmed life. Italians found Australian Catholicism ‘insipid’. Australian Catholics accused Italians created their own space within the Church in Australia and had their own priests but not separate parishes as in the United States. In the Catholic Church too, the movement was not all one way. For instance, early in the 1980s, in response to an appeal from Cardinal Giovanni Benelli of Florence, Carmelite nuns from Melbourne revived a deserted convent in Tuscany.

Italo-Australian relations have had to survive the unpleasantness of war and the rigours of postwar migration camps. It was a shock for many Italian migrants when, during the Second World War, they were rounded up as enemy aliens for work camps, particularly for those whose sons were serving in the Australian forces. As one Queenslander said, ‘The trains taking fathers to internment camps passed those bearing their sons to join AIF units.’ Among those interned was Antonio Dattilo Rubbo who had been naturalised in 1903, six years after his arrival. An indignant letter to the Attorney-General from Mary Gilmore may have contributed to Dattilo Rubbo’s swift release.

Of the forty thousand Italians in Australia who were naturalised and the twenty-five thousand who were not, 3,650 were interned by September 1942. Some were anti-Fascists. Australia interned ten per cent of its aliens whereas the corresponding United States figure was one per cent. In part, the excesses of the internment policy were counterbalanced by the fact that some of the eighteen thousand Italian prisoners-of-war found Australia so congenial that, after repatriation, they returned to farm in the same zones they had worked as labourers.

There are some bizarre footnotes to wartime relations between Italy and Australia. One is that Australian war veterans visiting Rome in the 1960s refused to meet Italian First World War veterans until reminded they had been allies. Another is that Mrs Judith McKay, former art curator of the Australian War Memorial, has claimed many of the stone Diggers on Queensland First World War memorial pedestals are imported statues of Italian Alpine soldiers. In his novel Kangaroo D.H. Lawrence described an Australian stone soldier as ‘stiff and pathetic’, but the historian Ken Inglis noted that some Diggers on Queensland pedestals have Italian, almost angelic faces’. Flesh and blood Alpini, however, were excluded from the 1988 Anzac Day marches in Hobart because of protests from ex-Rats of Tobruk. Some Italian ex-partisans do march in Anzac Day parades, surprising those Australians unaware that Italy fought on both sides in the Second World War. The Alpini, however, were not war veterans but 1950s conscripts who had participated in the 1986 and 1987 parades. In 1988 the Rats must have decided they were altogether too matey; stone Alpini are more acceptable.

Many of the postwar migrants’ first experience of Australia was at windswept Bonegilla Camp alongside the Hume Weir. A former army and internment camp from 1947 until 1971 Bonegilla accommodated over thirty-two thousand migrants awaiting their first employment which immigration officials overseas had assured them would be found within weeks. Migrants thought the camp outlandishly remote from main work opportunities and Italian stomachs revolted at the predominance of mutton (and mutton fat) in the diet. Within a few weeks migrant camp blues set in. This occurred during the mid-1952 economic slump, when about two thousand Italians were marooned in Bonegilla for over three months. They gave vent to their frustration by setting fire to huts and a church before staging a demonstration outside the director’s office. It was feared that, unless work were found, they would burn Bonegilla. Soldiers and armoured cars were deployed outside the camp in a tense atmosphere which was dispelled eventually by negotiations. Some Italians were then shifted swiftly from this Heartbreak Hostel, if only to nearby Bandiana army camp where they found employment weeding.

Long before the Second World War Italians had been aware of the opportunities Australia offered. In the early 1850s Cavour decided it would be ‘handy ... and almost necessary’ to establish a consulate in Australia, and it was done before the decade was over. Nino Bixio, who was to be one of Garibaldi’s most aggressive generals, captained the Goffredo Mameli from Genoa to Melbourne in 1856 (with Cavour brand cigars in the cargo). The Goffredo Mameli arrived less than four months after the departure of Raffaello Carboni who, in 1848, had been in the same hospital as Bixio and the poet Goffredo Mameli, after all three were wounded fighting for the Roman Republic. Bixio had sailed to Australia as a partner of Genoese businessmen who wanted to establish a Genoa-SydneyManila-Tokyo-Genoa shipping line. Anticipating substantial migration from Germany and Switzerland as well as Italy once the Suez Canal was opened, they launched an Emigration Company and published a handbook for those going to Australia, but nothing came of the project.

Yet another prominent patriot, Manfredi Camperio, was in Melbourne about the same time as Carboni and Bixio. Camperio was a Milanese who had been imprisoned by the Austrians for his patriotic activities and had been a protagonist in a successful anti-Austrian uprising in Milan (known as the Five Days) in 1848. Robust, handsome Camperio, who had a moustache and chin-strap whiskers, came from a well-off family. Before leaving via London for the Victorian goldfields, he travelled widely in Europe and also visited Constantinople with a friend Alessandro Carissimi, a descendant of a renowned seventeenth century composer Giacomo Carissimi. Camperio anticipated hacking into mountains of gold in the ‘new California’, but, in fact, found little at Sailor’s Gully. (He referred to the Aborigines there as ‘Papuans’.)

Back in Melbourne he met a failed Covent Garden impresario and offered to landscape the garden of a restaurant the Englishman was building near the Yarra in Richmond. Camperio wrote that he had learnt in Australia a man should claim to be competent in activities he had never undertaken before; in other words, he should become a Giacomo-of-all-trades.

Shortly after he began landscaping, he had a delightful surprise. Alessandro Carissimi, his companion in Constantinople, arrived at his boarding-house together with another of Camperio’s friends. The pair had vainly sought a fortune in America and were now fishmongers in Melbourne. Camperio involved them in the landscaping of the restaurant garden. After the restaurant’s inauguration they continued to work by day in the garden and nightly, for two weeks, performed Bellini’s Norma with an orchestra and choir in a tent in the grounds. They also sang Italian popular songs but one evening spiced Milanese songs with improvisations that made fun of the English and Australians. ‘Someone must have understood’, wrote Carissimi, because the miners, who made up most of the audience, began to shoot and the trio fled.

Subsequently they sang English, French and Milanese songs with success in various Melbourne restaurants before working their passage back to Europe on a Dutch ship. Camperio, like Raffaello Carboni, was in time to join in the second War of Independence as an officer and welcome Napoleon II’s arrival in Milan.

Many Italian professional people, especially musicians and artists, made their presence felt in nineteenthcentury Australia. In the 1840s a political exile, Count Girolamo Carandini, brought Italian opera to Hobart and Sydney. Skilled northern Italian artisans (frame and glassmakers, carvers and gilders) such as Lawrence and Julian Cotta, John Campi came from London at the end of the 1840s to satisfy the nascent demand in Sydney and Melbourne for sophisticated interior decoration. From 1856 Angelo Torraghi, a Milanese inventor and ‘mathematical, philosophical and optical’ instrument-maker worked in Sydney where his clocks still function, for instance in the customs House facade and at the Phillip Street entrance to the Secretary for Works building. Governor Phillip’s statue in the Botanic Gardens is the work of Achille Simonetti who was the first sculptor instructor in the NSW Fine Arts Academy.

Guiseppe Prampolini, who was sacked from the Italian Public Works Ministry in 1899 for his Socialist activities, at the age of fifty left Venice for Sydney. There he joined the International Socialist Club and, on 10 July 1903, launched the first Italian language paper in Australia, the weekly Uniamoci (Let Us Unite), although there were not quite four thousand Italians in all Australia. It lasted just over a year because, at the end of 1904, Prampolini returned to Italy. In the 1930s, over eighty, he was a redoubtable Communist and antiFascist.

In the 1890s an excompanion-in-arms of Garibaldi (who had made a brief stop himself at a Bass Strait Island which he later recalled from his Caprera retreat), Vincenzo Fasoli, ran a cafe in Melbourne frequented by bohemians, including Randolph Bedford who was to spend several years in Italy. Fasoli was followed in this century by the ‘spaghetti mafia’ of restaurateurs, such as the Massoni, Triaca, Codognotto, Vigano, and Molina families, who have added variety to Melbourne’s cuisine. For coffee addicts, introduction of the Italian espresso machine in the 1950s seemed a welcome infusion of European vices.

Some Italians arrived in Australia by chance. The story goes that towards the end of the last century a certain Bartolo sailed from Lipari, in the Aeolian islands off Sicily, for the United States but the ship sank. The survivors were taken to the Azores. Although the next ship that arrived was headed not for America but for Australia, Bartolo boarded it. His letters home inspired others to follow him so much so that now there are twice as many of Aeolian origin in Australia (including as B.A. Santamaria and the editor of Il Globo, Nino Randazzo) there are in the Aeolian islands themselves. The father of the High Court Judge, James Gobbo, came to Australia because of a similar improvisation. He had returned to the Veneto region after migration to Brazil, but when he could not find a convenient ship to take him back to Latin America, sailed for Australia.

Early in the century, a dinner in Sydney in honour of Dattilo Rubbo could bring together a group of interesting Italians, including Socialist refugees, such as Francesco Sceusa and Quinto Ercole, and also Roberto Hazon. The latter brought Italian opera companies to Australia from 1890 to 1930. (In October 1988 his eponymous grandson came from Milan to Perth to conduct his opera about Raffaello Carboni.) At the time of the dinner attended by Razon and Ercole, a young engineer, who had been imprisoned in Italy for his Socialist beliefs, arrived in Sydney. He returned to Italy only in 1913 with his Australian wife Evelyn Mulligan and her daughter, also called Evelyn. She eventually married the poet Attilio Bertolucci; one of their sons is the film director Bernardo.

Three Tuscans who arrived in Melbourne late last century had distinguished careers. Pietro Baracchi, the Victorian government astronomer from 1900 to 1925, helped to set up Mt Stromlo observatory in Canberra. Among the achievements of Carlo Cattani were the planning of St Kilda Rd and the reclamation of the St Kilda foreshore, laying out the Alexandra Gardens and landscaping the Fitzroy Street gardens that bear his name. Ettore Checchi laid the basis for water conservation in Victoria as well as for distributing the Murray’s waters between Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. (Australian expertise in irrigation is now esteemed in Italy – not quite a circuit, perhaps, but certainly a channel.)

Although there were few Italian migrants before the Second World War they were often considered a threat. In 1924, four thousand Italians arrived as against eighty-eight thousand British, but, as the visiting Italian journalist Arnaldo Cipollina noted, ‘to read the newspapers and parliamentary reports, you would have thought Italy was about to invade the Commonwealth’. Smith’s Weekly was to refer later to ‘that greasy flood of Mediterranean scum that seeks to defile and debase Australia’. A recent counterpart of such contempt was the description, by the Italian Radical leader Marco Panella, of a neo-fascist parliamentarian Mirko Tremaglia not only as a ‘shopkeeper’ but as an ‘Australian shopkeeper’. The fact that Tremaglia is not Australian made this insult completely gratuitous!

One of Eve Langley’s characters liked and admired Italians but still believed in Australian racial superiority – until thwarted in love. Langley’s novel The Pea Pickers, first published in 1942, is the classic locus for celebration of Italian rural workers in Australia. As the narrator and her sister arrive in remote Victorian country districts looking for work, they find Italians who, for their part, must be surprised to meet ‘a couple of (female) blokes outer Zane Grey’, who knew Italian well. The narrator, a full-blown romantic seeking poetry and love, delights in the Italian: ‘Australia, Australia. Ah Patria Mia.’ Nevertheless, in her ‘narrow wisdom of youth, she confesses belief in Australians’ racial superiority and disbelief in racial intermarriage. Later, disappointed in her love for an Australian, she gives up her dreams of ‘being a great Australian, a pioneer of racial purity’ to ‘cling to Italy’. It is either/or; she does not see the possibility of the two cultures enriching one another.

As the self-assurance of Italians in Australia increased, there have been attempts to trace a continuous Italian presence, often beginning uncertainly with James Mario Matra, the New York-born Corsican who accompanied Captain Cook. More convincing candidates may be Antonio Ponto of the Endeavour or the navigator and explorer Alessandro Malaspina who commanded two ships which reached Sydney in 1793. Malaspina was employed by the King of Spain and could stand for Italians who found work under a foreign flag.

Less attention has been paid to the long history of Italian-Australian imaginative links. Already in 1823 in the Sydney Gazette a woman was recalling a romance in Sicily. Her poem ‘Recollection of Former Happiness’, signed Psyche, must have been one of the first in Australia about continental Europe:

Oh, happy was such eve and day,

No care did us annoy;

And oft in sportive, youthful play,

I called him my Italian boy;

And he would smile when I have said

That he was mine alone

And called me his Austral maid,

Young Guido of Verone.

Among the Australians who have written in and of Italy are Alan Moorehead, who for a time inhabited the Florentine villa of the Renaissance poet Poliziano, Jack Lindsay, Frank Clune, Morris West, Janine Burke, Shirley Hazzard, Kate Grenville, David Foster, Peter Porter and Randolph Bedford, who lived in Tuscany for three years at the beginning of the century but preferred its harsh, poor southern zone to what he called ‘the Italy of “precious Mr Ruskin and his beastly Botticelli”’.

For their part, Italian writers have populated Australia as they pleased. Count Zaccaria Seriman (1709–84) was a descendant of an Armenian family which came from Persia to settle in Venice. The Seriman family were immigrants or, rather, refugees and Zaccaria continued to travel in imagination to Australia. In Viaggi di Enrico Wanton he described an Austral society where the lawyers are dishonest, the doctors ignorant, the women false and frivolous partly because of the ideas they imbibe at the Opera. Its newly rich businessmen are particularly obnoxious and the Prime Minister is a ‘big, shrewd and shifty type with a glib, ready and penetrating intelligence’.

Prophecy? No. Influenced by Gulliver’s Travels which had appeared twenty-three years earlier, Seriman was using an imaginary Austral land to criticise the social climbing, venality and trendiness of venetian society. He peopled the ‘extraordinary continent’ with monkey-faced people whose capital was Scimpoli (Monkeywille).

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, Abbe Scipione Bonifaco wrote a pamphlet sequel in which Frederico found the Austral land ruined by infiltration of the Cockheaded. Again, this may seem prophecy but instead it was a reference to the French Jacobins who, in Bonifacio’s opinion, but for the Hapsburg’s invasion would have ruined the Venetian republic.

Although these works concern only Venice they also show that, as Australia swam indistinctly into Europeans’ ken, geography was dead at last. For some European imaginations the discovery of Australia meant not the disclosure of a new world but the closure of the old. They used Austral exoticism to throw the homeland into sharp relief but the Southland also served to show that there was no second chance, no real Other, no new world, no escape. ‘I’ve seen the world’, Enrico concluded, ‘and behaviour is the same everywhere.’

About two hundred years after Seriman, in 1932, Filippo Sacchi published the first Italian novel about Australia based on direct experience. Set in Ingham in 1925 it arose out of a visit Sacchi had made to Australia as a roving correspondent for the Milanese Corriere della Sera.

In 1935 Giovanni Descalzo, who was to write several books about Australia, arrived in Fremantle on the Remo. Born near Genoa in 1902, he had little schooling but both his poetry and prose had been well received. Descalzo, who was proud of what he believed was the prestige of Italy had acquired through Fascism, was wearing a Fascist lapel badge when the Remo berthed. Shipping roundsmen were told he was an important writer. Asked his political opinions, Descalzo wrote in a reporter’s notebook the slogan, ‘Mussolini ha sempre ragione’, Mussolini is always right. As a result, Australian papers reported that an important Fascist had arrived on an official mission which put the police on the alert and made Descalzo feel, he wrote, like Gogol’s Inspector-General, an ordinary mortal mistakenly taken as a VIP.

On the Conte Biancamano in 1939, as assistant projectionist this time, Descalzo made a second visit which led to the Australian chapters in his travel book Ai Quattro Venti and a novel on an Italian boy’s trip in a sailing ship from Fremantle to Genoa, Al Lungo Corso. Apart from Gino Nibbi, he wrote more about Australia than any other Italian author. Understandably Nibbi proposed him as Director of the Italian Cultural Institute in Melbourne but Descalzo, in 1936, asked him to desist even though Roman authorities seemed favourable. Descalzo was too attached to his birthplace but he may also have recalled his first experience of central Melbourne where Nibbi advised him to lower his voice, to speak slowly and, above all, not to gesticulate. It was customary, Descalzo later wrote, to be 1ifeless and starched’ – expansiveness and enthusiasm were considered Southern European weaknesses.

As Descalzo did not have a romantic image of Australia, it did not delude him. For him the sea stretched invitingly from Genoa to Fremantle, he liked to depart, he enjoyed new countries but also returning home. Other Italian writers preferred to keep Australia as their dreamtime: the Milanese novelist Luigi Santucci pretended to have a relative in Australia when he wrote In Australia con mio nonno; Giorgio de Chirico, who liked the incongruous in his prose as in his paintings, wrote of a building reminiscent of a ‘German consulate in Melbourne’; the Sardinian novelist Salvatore Satta described the laying of a stone in a Sardinian village ‘just as they did in Canberra’.

Italo Calvino, a connoisseur of imaginary cities, could hardly resist the lure of Canberra: one of his characters married ‘a certain Sullivan’ there in 1912. In Cosmicomics Calvino wrote of ‘one among the eight hundred thousand flakings of a tarred wall in the Melbourne docks’. His The Cloven Viscount ends with the arrival, in the imaginary country Terralba, of Captain Cook who takes on board a Dr Trelawney with whom he plays cards. As the ship sails off, the sailors intone an anthem, ‘Oh Australia’, and the the narrator runs towards the seashore crying ‘Doctor Trelawney! Take me with you!’. Calvino himself did not want anyone to take him with them to Australia. He was invited but preferred to sit on his terrace observing gecko. Perhaps he did not want to meet a metaphor or spoil the imaginary by visiting it.

Umberto Eco, however, not only visited but on a beach in Australia found help in writing Foucault’s Pendulum. Prevented by tennis elbow from swimming, he chanced on an article about the reform of the Gregorian calendar, which aided in the novel’s construction.

For knowledge of Australia, Italians have relied more on newspaper reports than on novels. Mario Praz and Alberto Arbasino each spent only a short time in Australia but wrote copiously about it. Praz, sixty-nine at the time of his trip, visited all States but Australia was hardly suitable for a scholar who preferred the past and the peculiar. He acknowledged many modern amenities in Australia but took them as a matter of course. Alberto Arbasio, a novelist and cultural commentator with unbounded admiration for Praz, sent reports from Australia in 1974 which showed that at least he had spoken with Australians and had contemporary interests. Probably the fact that he was forty-four when he made his trip contributed to the difference. In his travel book Trans-Pacific Express, Arbasino included an essay which, although entitled ‘Australia’, is restricted to the Adelaide Festival of 1974 with a glance also at Sydney, which he called an ‘imitation America (both New York and San Francisco) resembling the real America of twenty years ago’.

Arbasino found Australia anxious to catch up culturally, in a ‘we want everything immediately’ mood expressed in the Sydney Opera House and plaques such as the one that states ‘remains of 1870–80 wall’. (In Rome, he noted, nothing similar is affixed even to the Servian walls dating from about 380BC.) He described the Opera house as a ‘white elephant among the most gross and hallucinating, and useless as Rome’s monument to the Unknown Soldier’. The Opera House exterior, ‘covered with shiny lavatory-like tiles’, Arbasino saw as ‘four playful turtles which, standing on their hind legs, each leaning on the back of the one in front, bugger one another’. The theatres, he continued, had to be adapted to the turtles as if one inserted little television sets in a series of various-sized Easter eggs. As a result, there are horrid ‘tiny stages, curving, lacquered, white wooden seats with tramway-like padding which recall kitchen appliances, no carpets but only wood as if on a motorboat, for who-knows-what particularly Australian acoustic reasons …’

Arbasino found Australians have ‘mild, lake-like blue eyes, a bit bovine amid magnificent-vulgar feature which resemble, inevitably and enjoyably, those of sheep and lambs’. The politicians he saw in action in Adelaide reminded him of Roman grocers who ‘expend pounds of sex appeal to sell a few ounces of mozzarella cheese’.

Andrea De Carlo, a young (thirty-one at the time of his visit) novelist, touted by his publisher as ‘Italy’s only yuppie narrator’, wrote on Australia for the Corriere della Sera in late 1983. Unlike Arbasino and Praz, he had Australian friends from an earlier visit and described encounters made through an extensive network of acquaintances in a country full of ‘curious and hospitable people’. He met those who boasted of Australia’s abundant resources but also young people keen to opt out of utopia.

Other series of articles have continued to appear which usually contain surprises such as Clara Falcone’s claim, in the Roman II Tempo of July 1987, that all Australians obtain a pension from the age of sixteen. As there is no regular coverage from Australia, surveys tend to be once-over-lightly affairs. They resemble conferences on Australian literature in Italy: it is difficult to move them beyond square one. Read together, the articles are like a novel composed of the first chapters. In the Italian press, Australia is always being discovered but never penetrated.

Although migration has intensified relations between Australia and Italy, migrants usually find their experiences bittersweet. Poetry is not the only thing that suffers in translation.

‘Talking a different language’, says Lorri Whiting, an Australian painter in Rome, ‘enables expression of quite different thoughts – it’s a new you.’ This liberating consequence of migration must be balanced against the words of Giannina Salvetti, an Italo-Australian actress in Rome who says she can really mean ‘I love you’ but, for her, the Italian equivalent ‘Ti amo’ remains just words.

DROP CAP

My main concern is with migrants who, despite all, remember the old ‘you’, who have stake in both countries and accept the complexity of continuity. Migrants find themselves in another place, living another life, but in the same world and often believing themselves unchanged. They are faced by the quotidian strangeness of transplantation.

Migration produces many misfits. Sometimes those who change countries make unwarranted comparisons, for instance between Mediterranean villages and Australian cities and, consequently, reach mistaken conclusions. Some become hypercritical, dissatisfied both with their adopted country and their homeland. Some become progressively less assured of their reasons for migrating while others make a virtue of necessity by relentlessly lauding the country where they are marooned over the one they left. As Dino Camillo has found, fifty years after being sent to settle in Australia, the experience can be ‘unsettling’. Some try to protect their children from being caught in-between by not taking them to visit the ‘other’ country. As a result, it becomes a magnet.

Migrants can meld the best qualities of both their countries but instead often combine the worst. They may hold both countries together in imagination only to find that, in fact, they are cruelly distant. Although changing countries means a new start it also implies, to a certain extent, living in disguise. Many migrants have a double identity. A Roman in Sydney, Renato Maffei, explained the migrant’s situation effectively with a sporting expression: he is always playing an away game. Distant from the aging, sickness, and death of friends and family in their homeland, it is as if migrants inhabit a time capsule. They suffer from their inability to bilocate. Often they become living fossils having only superficial contacts with their adopted country but preserving an outdated image of home. They have changed countries but countries change too.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.