Overland 100

$4.00; subscriptions $16.00 p.a.

Overland 100 edited by Stephen Murray-Smith

Perth, like Sydney, is a city of water, but the water on display is safely enclosed in the reaches of the Swan. Here ferries and commuting speedboats plough their straight lines among flocks of red or blue sailed dinghies sailing and tacking in sudden turns like flocks of tropical fish. In Fremantle, sailors’ missions and clubs straggle around the side streets, and the mall on a Saturday afternoon is left to drunks and kids on BMX bikes. In the Book Market casual browsers can look through the latest publications from Australia and abroad, or climb upstairs to find a collection of raw socialist writings dedicated to Pat Troy, ‘one of Australia’s finest working class fighters’. In the harbour, the tug named after this militant waterside leader may be bringing in the Irene Greenwood, flagship of the state fleet and named after the pioneer feminist and pacifist. Down the street, the holiday makers soak up the sun on the terrace of Papa Luigi’s, the Asian food mart is crowded with families eating out cheaply on the riches of the orient, and next door, in the restored Freemasons’ Hotel, now known as the Sail and Anchor, a younger crowd listens to a group of ·energetic folksingers, ‘The Sad Fish’. Liquors on tap include, Swan, Guinness, and the pub’s own potent brew, which must rival Coopers as the only real beer still made in Australia.

Yet, although Fremantle is unmistakably a waterfront town, it is almost cut off from the sea. Certainly, you can drive down the mole and clamber over the piled rocks until you join the fishermen in their view across the grey waters to ‘Rottnest in the distance, or look south over container wharves, cranes, and the varied works of a port. But the very business of the harbour shuts out the ordinary person from its activity. This may be why Australians, clinging to the periphery of the continent, are nevertheless more fascinated with its harsh· inland than with demanding ocean surrounds.

Down by the Fremantle waterfront, at Cicirella’s you can still buy a packet of old-fashioned fish and chips and sit on a waterfront bench to eat them. Certainly, instead of six pence’s worth, the minimum order is for three dollars’ worth, and they come wrapped in butchers’ paper instead of newsprint, but they still taste as good as fish and chips used to do. And, to be fair, the packet is really a generous bob’s worth.

The benches are so placed that while you eat you look out across a grubby little harbour at a boatbuilding works where the luxury craft of the rich are being assembled. Very like Footscray, although Fremantle waters seem dirtier than those of the Maribyrnong. But the real excitement of eating there is the contest with the seagulls. They come from everywhere, raucous and persistent, like a crowd of extras from Hitchcock’s ‘Birds’. If you want to enjoy your purchase you need to keep it covered, and don’t hold a piece of fish too long in your hand to feast your eyes on its rich golden brown batter before you transfer it to your mouth.

A different vision of a seagull adorns the cover of the one hundredth issue of Overland. A Fred Williams icon soars in rich ochre above a list of names representing the whole span of Australian writers, young and old, left and right, poets, novelists, reviewers and essayists. There is no implicit claim of superiority, but a feeling of good company jostling together in a crowded gathering united only by a belief in the importance of words and people. Williams’s seagull represents them all. Its feet trail earthwards, its solid beak probes firmly ahead, but its wings lift it strongly upwards in the freedom of the air.

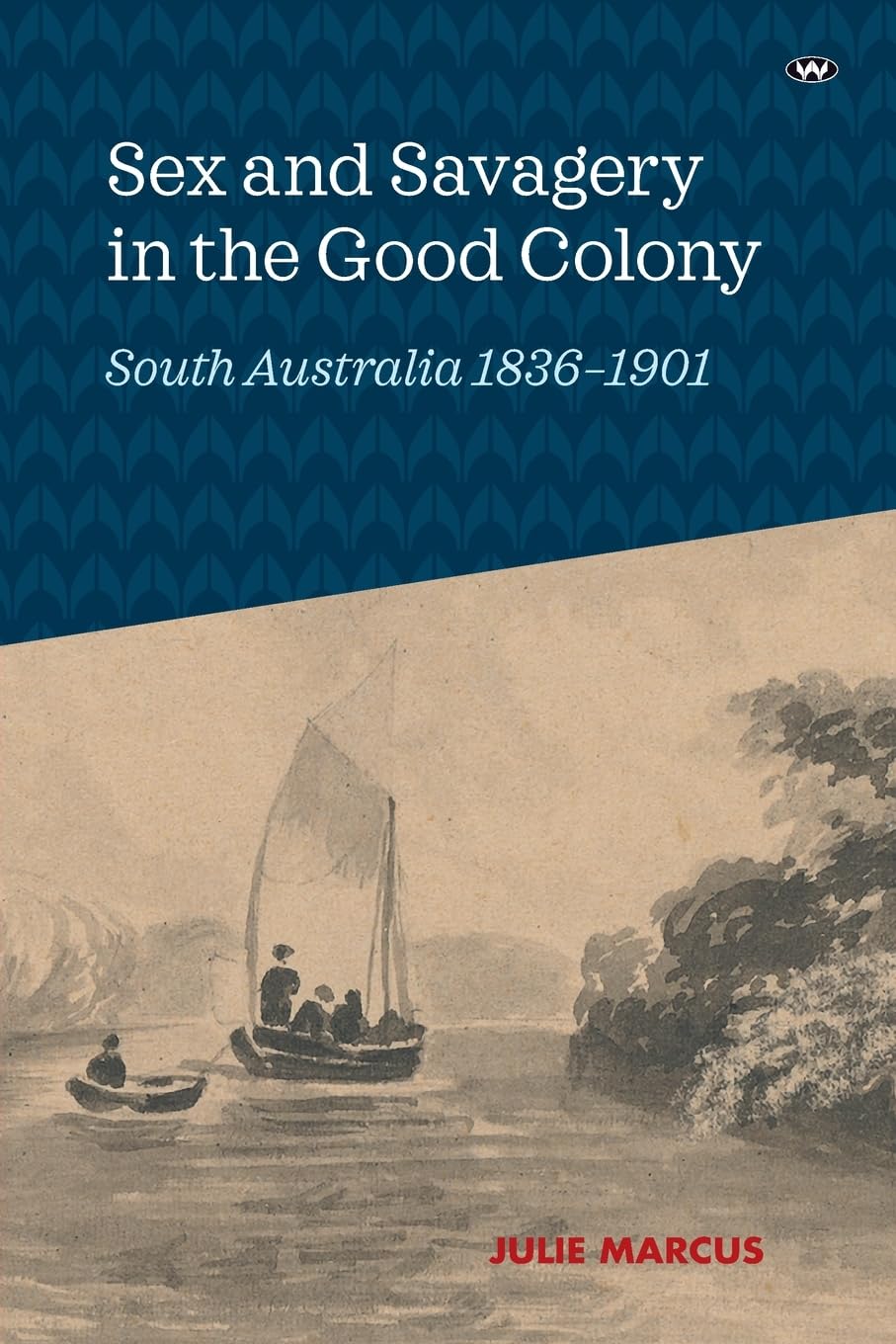

Perth, a city of seagulls, retains many of the contradictions of the society from which Overland emerged in 1954. It has torn down the past of its central city, replacing it with freeways and glass, but King’s Park still keeps the bush nearby. It kicks the poor out of their Fremantle lodging to make way for America’s Cup visitors, it is fearful of Aborigines, its press is good on news and poor on debate or anything concerning the mind. It prosecutes naughty eastern comedians and demands action against naughty words on the ABC. The WA Fellowship of Australian Writers meets in Tom Collins House and succeeds in bringing together writers, of quite diverse views, from Vic and Joan Williams, stalwarts of the old left, to Mary Durack, chronicler of the pioneers and unswervingly generous friend and supporter to fellow writers of every ilk. John and Rae Oldham, veterans of postwar reconstruction and socialist activities in the east, returned to Perth as pioneers of landscape architecture, and have both curbed the excesses of barbarism and clothed the freeways in beauty. Their book, Gardens in Time (Lansdowne, $30), a history of gardens in idea and practice from the earliest times, is a monument to humanism. While Sydney wallows in corruption, and Melbourne goes through moral agonies over the dismissal of a governor who has been caught freeloading, and the east as a whole enters a period of industrial and agricultural decline, the west continues to face the future while debating eternal verities.

Overland is like the winters of Perth in its mixture of tolerance and idealism, its belief in the importance of our past and its hopes for a better future. Stephen Murray-Smith, its founder and editor, is passionately interested in the sea and all its ways, but his journal turned inland for its name and inspiration. It came from a left which felt itself both embattled and pure in the face of the philistinism of Murray-Smith was to characterise as the ‘seemingly endless years of the Ming Dynasty’. Its first issue had a Noel Counihan drawing of mates ‘Off to the Diggings’ on the cover, above a list of contributors which included Nettie Palmer, John Morrison, Katharine Susannah Prichard, Eric Lambert, David Martin, and A. D. Hope.

The exchange of poems between Hope and Martin was to lead to anguished discussion among realist writers about the propriety of allowing reactionary and élitist criticism of one of their own. The first poem in the issue, ‘Swans in Footscray’, by Nell Old, spoke of ‘chemicals tainting the water’ while untroubled black swans recalled ‘how close to industrial suburbs / Are spacious acres free to sun and moon.’ For thirty years now, Overland has kept these spacious acres free for its readers.

I first came across Overland when it advertised a year’s subscription in the long since and sadly defunct Voice as ‘Australia’s best five-bob’s worth’. Since then, like Cicirello’s fish’n’chips, its price has risen from a bob to three dollars, and now to four. It has in the last twenty-five years become a part of my life, I have shared in the task of editing, and the editor and his family are trusted friends, so I can in no way look at the journal dispassionately, let alone objectively. Yet I believe it still retains the qualities which first attracted me to it, and which it shared with the earlier Bulletin at its best – openness, a belief in Australia and in a socialism which remained democratic and free of sectarianism, interest in new writing and ideas, and, above all, a commitment to its readers, to whom it gave a voice in its columns and to whom it spoke in prose and verse without condescension. The century issue maintains these values, except that – sign of the age of professionalism – the readers are no longer present in print.

The issue opens with ‘The Brass Jardinière’, a chapter from David Malouf s autobiographical novel. This appears to be an exercise in nostalgia, as the narrator recalls in intricate detail the house of his Brisbane childhood, but as he moves his focus from his parents and the circumstances they made to the wireless, the piano with its world of potential waiting for the human agent to release, and finally to the contents of the jardinière, we realise that his concern is not with a lost past but with unrealised potentials, the things which could not happen because other things did, and above all with the twin, the person he did not become but which is always within him.

Other contributors vary this search for times and people lost. Barry Jones recalls the cruelties and excitements of a St Kilda past, and the isolated boy whom I remember as a polio victim – he does not mention that epidemic – and he as a spastic. Majorie Tipping recalls the Palmers – two of the contributors to the first Overland. Frank Dalby Davison appears from beyond the grave in a story about the dog which adopted his family, Michael Davies recalls Fred Williams, Judith Wright recalls Brisbane in wartime, with its opportunities and frustrations, her encounters with Meanjin and the Christensens, and her decision to stay in Brisbane when they went south: ‘I don’t know that I was ever quite forgiven for deciding to stay in Queensland’. No nostalgia in any of these, but a search for the origins of what has given value to the writers’ lives.

Poetry has always caused Overland problems. When it has been accessible, it has often been banal; locked in trite rhythms or expected images; when it has explored new ideas and experience, the readers have often found it intimidating or inscrutable. The present issue contains a poem by Patrick White which partly expresses this sentiment and then answers it. Other poems include Barbara Giles dancing a madrigal on the tightrope of age, Elizabeth Riddell talking of seminars and wordboxes, John Millett noticing a fisherman, Chris Wallace-Crabbe describing a fantastic Captain Melbourne. All are verbally alert, clear, amusing, insightful – bringing both delight and meaning. Eric Beach and Shelton Lea write in a different mode, remaking language to speak in a common tongue from the far edge of experience. Alan Gould has a long, reflective poem to Les Murray, and Barrett Reid, Overland’s poetry editor, has a similarly long poem on light and space, and the miracle of human creativity. John Croyston writes a footnote to a Sydney encounter. The poems not only provide for all tastes, they enlarge and unify our perceptions of the world.

As usual, the issue contains select reviews, and a long anti-review essay by Paul Carter. This essay, starting from a discussion of Xavier Pons’s book on Henry Lawson, which he finds important only as an example of the academic industry of literary criticism, raises the question of whether any review can escape being a part of the ‘mind-industry’, giving importance even to what it rejects by the mere fact of discussing it. Underlying the essay is Adorno’s notion of language as a seamless web entrapping our every use of it in the ideology and class structures of our time. Thus reviewing, criticism, and scholarship lock acts of creativity into safe boxes, subjecting them to the control of established techniques, putting them on display as a catalogue of human variety rather than allowing them to create possibilities for their readers. Yet the very urgency of Carter’s argument does, like the best reviewing, criticism, and teaching, lead us through its theories back to a point of liberation where we can again engage directly with Lawson, seeing his work more clearly not because it is placed, but because it is freed from some of the presuppositions he or we have brought to it.

This hundredth Overland combines the marauding urgency of the seagulls with their soaring spirit. Its writers look to the past to establish a foundation for the future. Like David Malouf’s narrator, they are concerned with what we are, how we came to be this way, and what we could be. The one hundred democratically quarrelsome and matey issues of the journal provide a sound foundation for more centuries of exploration of this territory. As Australia becomes more globally entangled, so this endeavour is likely to give more attention to what is happening overseas, and to problems of post-industrial society rather than to the industrial capitalism which Overland was founded to oppose. Yet, if the origins of contemporary Australian society and its problems lie overseas, our grubby and unyielding island continent gives us a particular perspective from which to view them. Like the seagull, Overland starts its seaward excursions from this landward base, but its true home is with the free surge of the winds above.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.