Letter from London

Miss Julie ★★★★

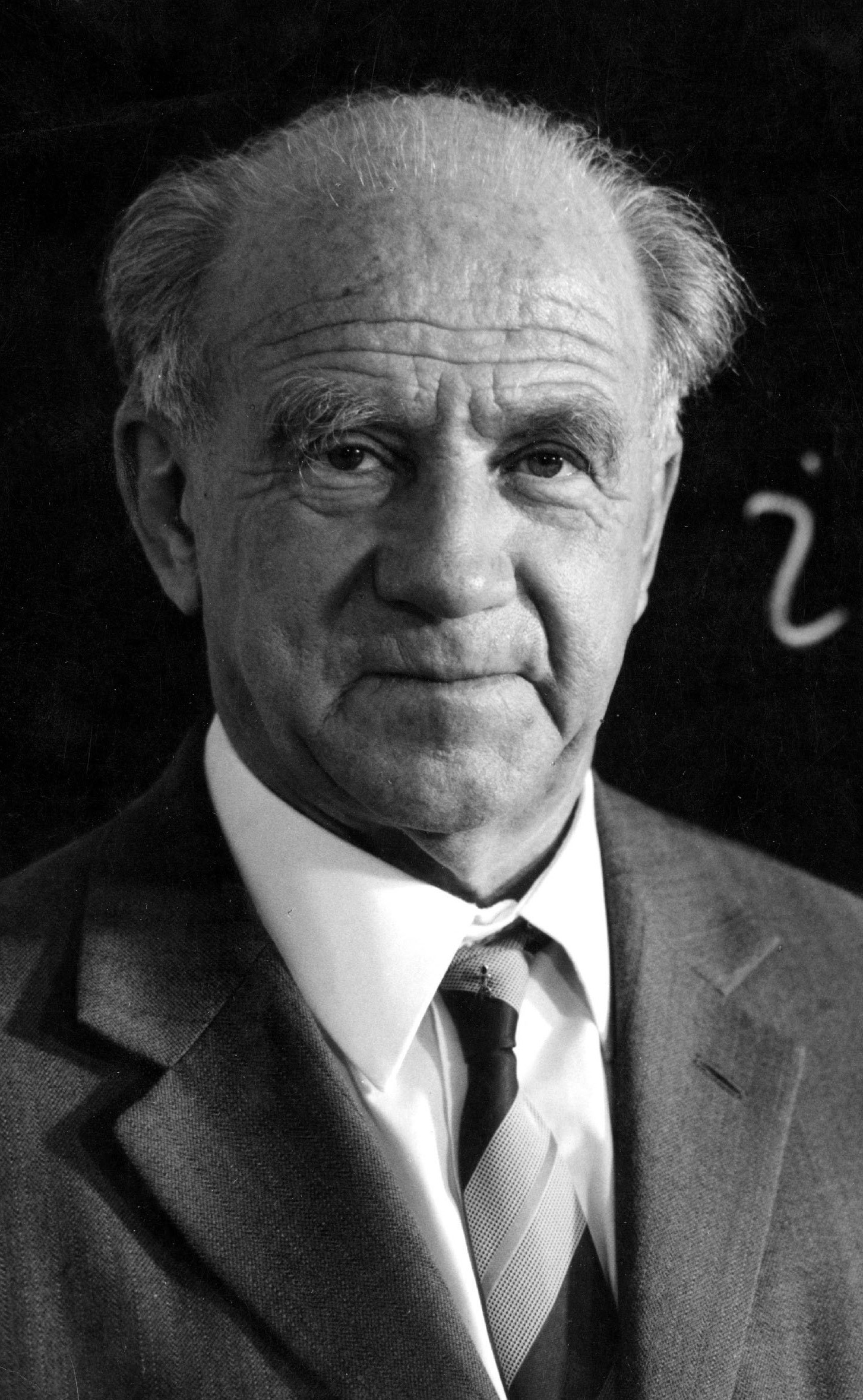

Rosie Aldridge and Benedict Nelson in Miss Julie (photograph by Tom Howard/BBC)

Rosie Aldridge and Benedict Nelson in Miss Julie (photograph by Tom Howard/BBC)

The name William Alwyn (1905–85) conjures up memories of that golden age of British cinema in the late 1940s and 1950s. He produced more than seventy film scores and dozens of works for orchestra and piano, as well as a healthy output of chamber music. In later years he produced a couple of operas, only one of which attracted attention.

Miss Julie was written during Alwyn’s years of semi-retirement in Suffolk and was first performed in 1977, then recorded in 1983 with a fine cast including Benjamin Luxon, Della Jones, and Jill Gomez in the title role, with the Philharmonia under Vilém Tauský (Lyrita). It was not revived until 2019 when the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sakari Oramo gave a semi-staged performance at Barbican Hall (October 3) with soloists soprano Anna Patalong in the title role, baritone Duncan Rock as Jean, mezzo-soprano Rosie Aldridge as Kristin, and Australian tenor Samuel Sakker as Ulrik.

Based on August Strindberg’s rather claustrophobic play of the same name, Miss Julie exemplifies Alwyn’s approach to writing opera: keeping the drama transparent, the characters distinct, and moulding the music to fit the rhythms of speech. There are subtle reminders of Richard Strauss and Alban Berg, along with Alwyn’s own melodic style and skilful orchestration, so apparent in his film scores. The work is mostly tonal, romantic, and warmly lyrical – possibly too cinematic for some, yet demonstrating that Alwyn saw film music and operatic music fulfilling similar dramatic functions.

The opera, set in Sweden in the late nineteenth century, revolves around the upstairs–downstairs love triangle of the daughter of a Swedish Count (Miss Julie), the valet (Jean), and the cook (Kristin). The Count is absent, having left his daughter in charge. Kristin intends to attend the Midsummer dance with Jean until Julie has other plans. She and Jean have an affair despite her alleged erotic feelings for the gamekeeper (Ulrik), who discovers the lovers together. They plan to elope, with Julie stealing money from her father. When the Count returns, their plot is discovered and Julie decides that she will commit suicide like her mother before her.

The four singers were well matched. All possess operatic backgrounds and experience, having all sung in the world’s major houses. Appropriately, they were superbly directed by Kenneth Richardson, whose career has spanned opera and music theatre. In the days following this performance, the BBC Symphony and the four singers recorded the score for broadcast and release at a later date.

Performance attended: 3 October 2019.

Werther ★★★★

Isabel Leonard and Juan Diego Flórez in Werther at the Royal Opera House, London (photograph by Catherine Ashmore)

Isabel Leonard and Juan Diego Flórez in Werther at the Royal Opera House, London (photograph by Catherine Ashmore)

From the rare to the familiar. Benoît Jacquot’s excellent 2004 production of Massenet’s Werther has seen its third revival at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, under revival director Andrew Sinclair and conducted by Edward Gardner. It tells the story of Werther’s hopeless love for Charlotte, who has been promised in marriage to another (Albert), and the ensuing tragedy.

American mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard made her house début as Charlotte and was convincing both vocally and dramatically. Her letter scene in Act III was superbly sung. Unfortunately, the Werther of Juan Diego Florez was disappointing. Once one of the world’s best interpretors of bel canto, Florez has moved into a heavier lyric repertoire in recent years, and this does not suit his voice ideally. ‘Pourquoi me reveiller’ was well sung, with beautiful shading and emotion, but at other times his voice lacked strength, especially in the climactic scenes with their lush orchestrations.

The other roles were well sung. South African baritone Jacques Imbrailo was a fine and upright Albert, suitably lacking the emotion of the other party in this tragic ménage à trois. Heather Engebretson was a coquettish and naïve Sophie, her clear and bright soprano contrasting with the mezzo of Charlotte. Alastair Miles was in fine voice as the rather bluff Bailli, and there was an effective supporting cast in the minor roles.

The lighting and sets of this production, though rather basic, were dramatically appropriate, particularly in the last act, in which the room in which Charlotte attends the dying Werther moves forward on stage, increasing in size as the drama reaches its climax.

Edward Gardner’s conducting of Massenet’s ravishing score was impressive – at times Wagnerian and always romantic and poignant.

Performance attended: 1 October 2019.

Don Pasquale ★★★☆

Damiano Michieletto’s new production of Donizetti’s Don Pasquale for the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, has given Bryn Terfel a role that suits him in every way. Donizetti wrote more than sixty operas over twenty years – mostly historic and romantic dramas. Pasquale was his comic masterpiece, and the new production does not disappoint.

The elderly bachelor Pasquale plots with Dr Malatesta to wed the sparkling Norina. She ends up with her true love Ernesto (Pasquale’s nephew), while Pasquale finishes up in a wheelchair, his fortune somewhat diminished. A revolving stage and contemporary sets and costumes are not out of place in this opera buffa. The addition of puppets and video gear are at times distracting, but silly old men behaving badly are just as relevant today as when the work premièred in 1843.

Terfel’s role reminded me of his Falstaff. The voice is still in good shape, though occasionally a little rough around the edges. The Armenian baritone Markus Werba was also convincing and a highlight of the evening was the famous tongue twisting Pasquale/Malatesta duet, sung while both characters operate hand puppets throughout.

Russian-German soprano Olga Peretyatko, in her house début, was a delightful Norina with a natural comic flair. At times she was a little harsh in her upper register but otherwise was in full command and looked glorious while being prepared as Pasquale’s prospective bride. The Ernesto of Romanian tenor Ioan Hotea was less impressive. At times his tenor was strained, with a marked vibrato, especially in the lovely aria ‘Povero Ernesto … Cerchero lontana terra’.

Evelino Prido conducted the bright score with precision and elegance.

Performance attended: 21 October 2019.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.