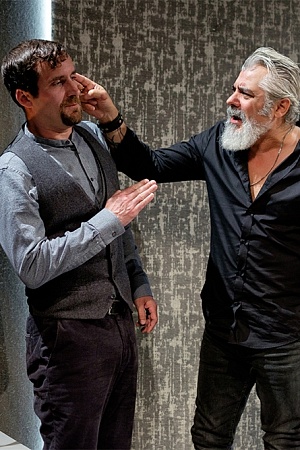

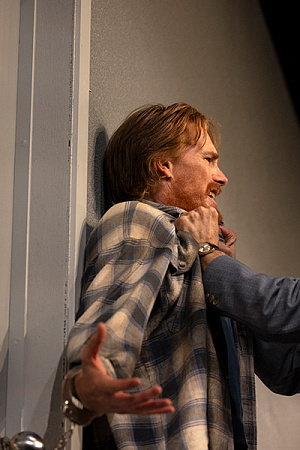

Waiting for Godot (Wits' End / Eleventh Hour Theatre) ★★★

Estragon: And if we dropped him? [Pause.] If we dropped him?

Vladimir: He’d punish us. [Silence. He looks at the tree.] Everything’s dead but the tree.

The original French version of Waiting for Godot was written in Paris between October 1948 and January 1949. This was a time of mass migration in Europe, when a flood of displaced humanity washed across the continent. It was a time of refugees, exiles, immigrants, fugitives, and transients. France settled more than 38,000 people who, for one reason or another, could not be repatriated. Australia took more than 180,000.

In 1953, there were still some 250,000 refugees awaiting resettlement in camps across Europe. These were the human leavings, the people deemed surplus to a world intent on reconstruction and forgetting: the elderly and the infirm, the crippled and the insane.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.