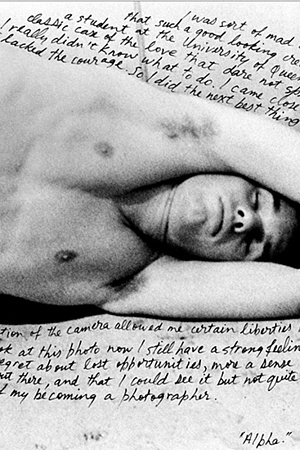

Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

This exhibition has a clear aim – to prove that Robert Mapplethorpe ‘is among the most significant artists of his time’. The evidence marshalled by the curators at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum is substantial. They have conducted extensive research, sourced outstanding vintage prints, and provided an illuminating chronological and thematic structure for the hang. Instructive signage placed at strategic points tells us that throughout his career Mapplethorpe sought perfection through photography which he considered the perfect medium because it was ‘intimate and immediate [and] a means of seduction, play and control’. There is a satisfying concentration of works in the key areas of his practice which, using the curators’ wording, comprises portraiture, homosexual and sadomasochistic scenarios, photographs of black men, and floral still lifes. Also included are Dada-ist, Pop-ish items from his art school years and two films (one involving Patti Smith, the other bodybuilder Lisa Lyon) which amplify the scope of his art practice.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.