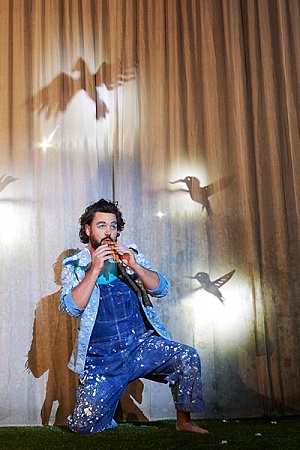

Siegfried (Opera Australia) ★★★★1/2

We know that Siegfried – third opera in Der Ring des Nibelungen – had a curious gestation. Wagner put it aside after writing Act II, as if weary of Siegfried’s progress: this improbable hero’s search for love, fulfilment, individuation. For twelve years Wagner was diverted by love of a metaphysical kind (Tristan und Isolde, 1865) and by a rich comic social panoply, (Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, 1868). When he resumed work on Siegfried in 1869, he did so with a new urgency and compositional brilliance. Unlike Das Rheingold (1869) and Die Walküre (1870), the opera would not be premièred until the first complete Ring cycle on 16 August 1876, one day before the première of Götterdämmerung. The venue was the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Wagner’s bespoke theatre, always intended to be temporary – but still there.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.