SAINTS

During the Interregnum – that brief but tumultuous period between the execution of Charles I in 1649 and the restoration of Charles II in 1660 – a new vision of sainthood burst into noisy prominence. For the pious mainstream, the true saints were the elect in their anxious, ordinary labour of conscience. Saintliness was understood as a private discipline of endurance. But the new breed of sectaries and millenarian radicals imagined it otherwise. Sanctity was to be a public vocation. Suddenly, sainthood began to look like a mandate not only to outlast the world, but to reorganise it.

Prophecy was the saint’s chief instrument for gaining access to power. On at least half a dozen occasions between 1647 and 1654, Oliver Cromwell and his colleagues halted their deliberations to admit a new prophet, often a woman, to deliver a message. Revelation enters. A voice without office addresses the men with swords. What happens when imminent deliverance is treated as a fact of public life and the messenger is precisely the person power has least reason to admit?

In this new play by stalwart Melbourne-based company Elbow Room, such prophecies appear not as decorative mysticism but as symptoms of a particular way of making history – a technology of politics, if you like. The script by company member Marcel Dorney – sprawling and full of knotty moral dilemmas – circles around contemporary issues in resonance with this radical form of sainthood: how conscience persuades itself it is authorised, how goodness recruits its politics, and how the desire to be right can be translated into action.

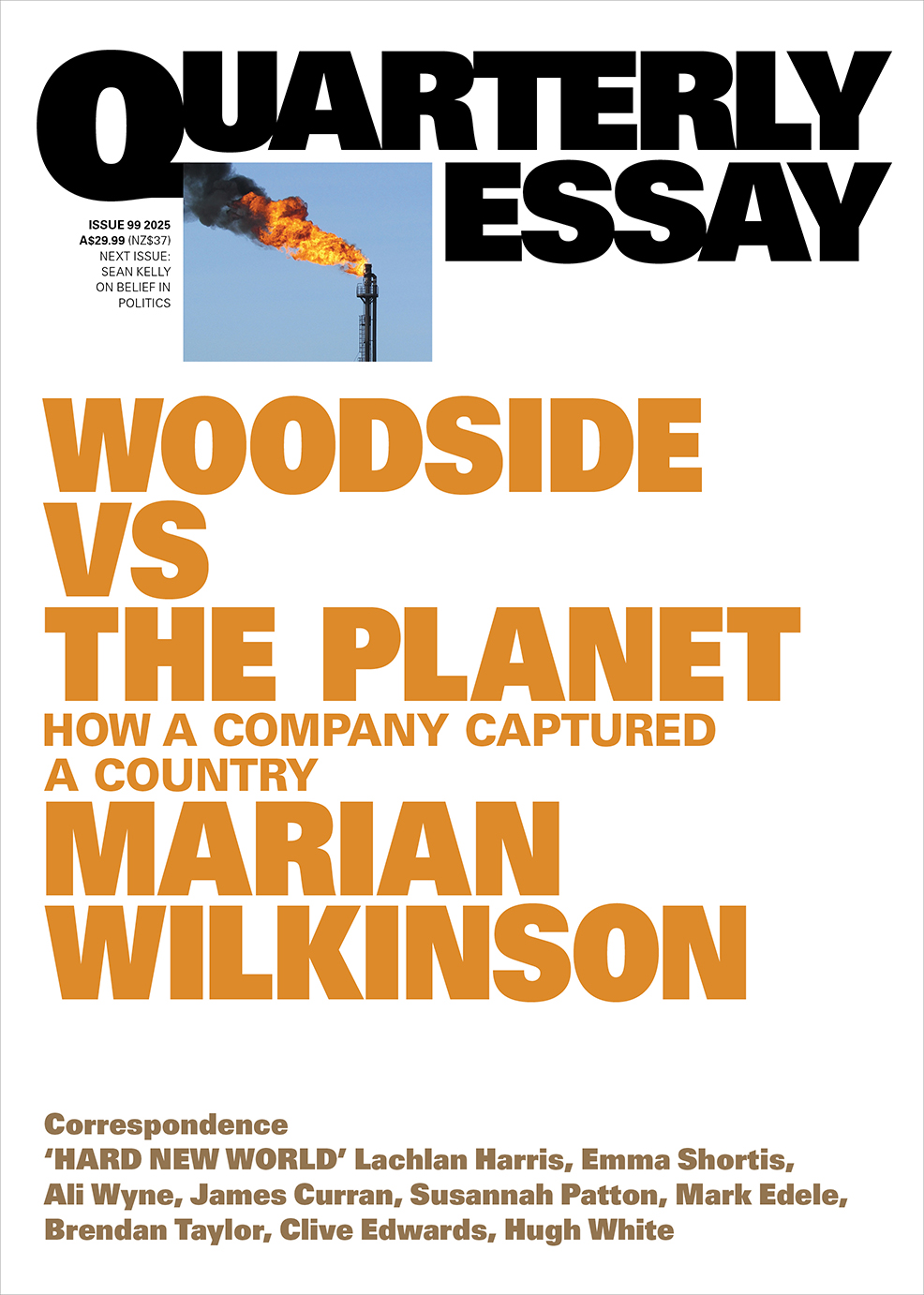

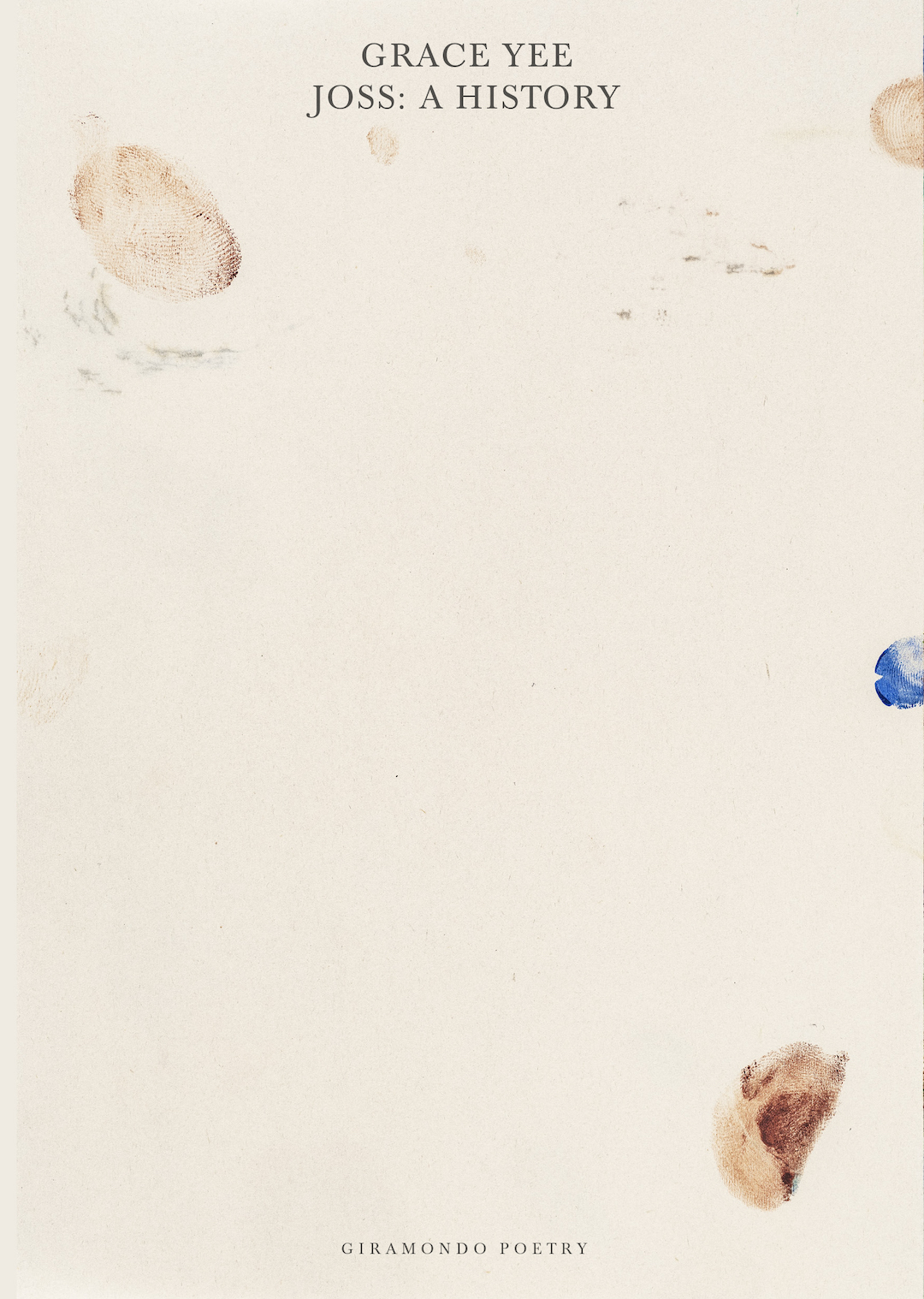

SAINTS by Elbow Room at La Mama Courthouse (photograph by Darren Gill)

SAINTS by Elbow Room at La Mama Courthouse (photograph by Darren Gill)

They have fixed on the real-life figure of Anna Trapnel, a Fifth Monarchist prophet whose notoriety is inseparable from the politics of the moment. In the pamphlets published in her name, prophecy is not a private rapture but a public address: the title page of The Cry of a Stone, from 1654, advertises visions ‘relating to the governors, army, churches, ministry, universities: and the whole nation’. Elbow Room makes its point early on: yes, women had a voice in this world turned upside down, but what exactly was their message?

In Trapnel’s case, the message is overwhelmingly scriptural. Her prophecies are a torrent of biblical language mobilised as political commentary. Her vision of Cromwell as a bull – in one of her best-known passages – is typical. He is not whimsy but a scathing critique, a statement of dissatisfaction with the new regime pressed into the service of apocalypse. The horizon of fanatics like Trapnel is not reformist uplift but purgation. They are the militant heralds of a thousand-year reign of the saints.

Elbow Room presents Trapnel as a figure of formidable personal charisma. Cait Spiker’s performance is very grand. She is brooding, grave, imperturbable, and occasionally incandescent. But the company also stages its reservations. It worries at what such certainty makes permissible and what it leaves unthought: massacres and colonialism, the defeat of the agrarian communes, the drift toward authoritarianism. By our lights, can she still be thought of as a saint?

They offer a contrasting figure in the fictional Frances, played by Briony Farrell. She’s a different kind of saint, one who is more acceptable to contemporary sensibilities. She is not a zealot – indeed, not religious at all. Instead, she is decent and humane and holds entirely acceptable opinions on slavery, conquest, and empire. And yet Frances is drawn to the prophet’s power. She cheers on Anna’s bold rebellion against the patriarchal order and her refusal of compromise.

Like the audience, she is left asking what it means to be in love with that power while fearing what it might license.

Frances, too, has a prophetic experience. Under the influence of a psychedelic decoction of some kind, she manifests a queer, quipping, time-travelling spirit guide, played by Zak Giles Pidd. Their wanderings through the universe together – while Anna languishes in prison – can be hard to follow, but eventually the guide turns nasty and begins advocating for a program of murder. The suggestion, faint but unsettling, is a continuity between seventeenth-century millenarian certainty and modern utopian zeal: not only to defeat your enemies, but to write them out of history.

SAINTS is billed as a satire, but what exactly is being satirised? It’s a loud, dialogue-heavy show, crammed with pocket history lessons. The steeply raked bleachers keep the action in your face at all times. Often the actors speak while extra text arrives by projector. Visually, it is dark, with black sheets and limited lighting. The cumulative effect is density. Ideas arrive in a rush out of the shadows, with little space to pause and think them through.

Anna Trapnel is certainly not satirised. Cait Spiker makes her a monumental presence, the still point around which the production whirls. Around that centre, scenes collide, the tone shifts, explanations are offered and then pulled away or laughed at. The company seems determined to goad its audience into active thought. They have something to say, but they do not say it plainly. There are explicit nods here to other playwrights who have used challenging forms to explore this same historical moment, Caryl Churchill and Howard Barker among them.

The satire is most obvious in the figure of Elizabeth, a spy played by Emily Tomlins. She gets both the best and the worst gags (I’m still unsure which category her popery-potpourri pun belongs in). Tomlins is lots of fun, though at times her shtick feels pitched for a different vehicle altogether, as if she is workshopping material for a slick streaming comedy about the Lord Protector’s favourite daughter, also called Elizabeth. Imagine it: a rambunctious child of privilege drafted into the post office under spymaster John Thurloe, dashing about the country doing dastardly deeds. In any case, here she seems to represent the bourgeois strand of the revolution, already sliding toward surveillance, finance, and extraction.

SAINTS is a fine expression of Elbow Room’s unflagging imaginative passion. There is live music, costumes with a punk accent, and a relentless sense of play. SAINTS returns us to that decisive moment in English history when the old order breaks and terrifying novelties are lowered onto the stage. Yet it is performed in a style recognisably their own, worrying at those uneasy connections with the here and now.

SAINTS continues at La Mama Courthouse until 20 February 2026. Performance attended: February 7.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.