Ron Mueck: ‘Encounter’

.jpg)

There is a particular sense of anticipation surrounding Ron Mueck’s return to Australian soil – his first since 2010. An immensely popular figurative sculptor, Mueck has built an international following through his uncanny, hyperreal sculptures of the human body. Recent exhibitions in Seoul this year at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and in 2024 at Museum Voorlinden in the Netherlands drew record crowds, as has his current touring exhibition from the Fondation Cartier in Paris. His Sydney survey, Encounter, presents just fifteen sculptures, understandable given the fact that his meticulous, labour-intensive works can take months, even years, to complete.

Visitors are greeted at the entrance by a towering naked woman in the advanced stages of pregnancy. The figure resembles a latter-day Venus of Willendorf, here as a contemporary emblem of fertility and creation. Standing eight feet tall, her stance is firm and grounded, defying the weight of her swollen belly. This apparent certainty dissolves on closer inspection. Her downcast eyes and tightened expression convey exhaustion, vulnerability, and doubt rather than pride. At once monumental and deeply human, the sculpture establishes a tone of emotional ambiguity that resonates throughout the exhibition.

Scale plays a crucial role in Mueck’s practice. His figures are either dramatically enlarged or unsettlingly small, destabilising the viewer’s sense of bodily proportion and psychological distance. Within the galleries, audiences encounter intensely private moments rendered public: a half-dressed couple spooning tenderly in bed; an older pair reclining beneath a beach umbrella; a group of snarling dogs frozen mid-attack; the viscera of a slaughtered pig. Each sculpture captures a suspended moment, inviting viewers to briefly inhabit an implied narrative before moving on. These scenes oscillate between the transcendent and the mundane, revealing the quiet drama embedded in everyday existence.

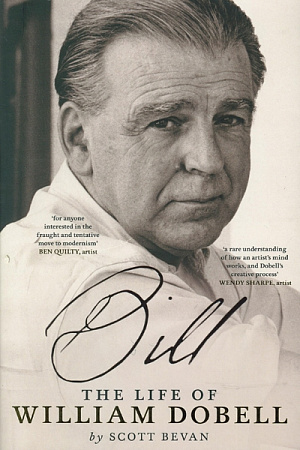

Old Woman in Bed (2000/2002) © Ron Mueck (Photograph by Felicity Jenkins)

Old Woman in Bed (2000/2002) © Ron Mueck (Photograph by Felicity Jenkins)

Underlying this emotional charge is extraordinary craftsmanship. Working largely alone in his studio on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom, Mueck typically begins with clay before casting his figures in resin or silicone. Each surface is painstakingly painted; individual hairs are applied by hand; clothing is carefully tailored or sourced. The result is an astonishing degree of physical realism. Given this slow, exacting process, it is unsurprising that Mueck has produced only around fifty works across his three-decade career.

Despite this technical precision, Mueck’s practice diverges from the aims of 1970s hyperrealism. Artists such as George Segal and Duane Hanson sought to replicate reality as faithfully as possible. Mueck, by contrast, distorts scale and exaggerates detail to heighten emotional resonance. Rather than offering objective replicas of the human form, he presents psychologically charged figures that compel viewers to confront their own vulnerability, mortality, and carnality. His subjects span the full arc of life – from infancy to old age – charting a journey ‘from the womb to the tomb’.

The sculptures invite close, almost voyeuristic viewing. Their surfaces reveal mottled skin, visible veins, freckles, scars, and wrinkles. Bodies are imperfect and weighted with history; faces are expressive rather than idealised. Gesture and posture become crucial signifiers: the overly firm grip of a teenage boy’s hand on his girlfriend’s arm; the slumped resignation of a corpulent man seated alone; the protective crouch of a young child. In the diminutive sculpture Old Woman in Bed (2000-02), the frail body of an elderly woman appears to shrink as her life force ebbs away. Mueck’s figures are not heroic or aspirational; they reflect the fragile realities of human existence.

Mueck’s path into contemporary art was unconventional. Born in Melbourne in 1958 to German toy makers, he relocated to the United Kingdom via Los Angeles, where he worked as a model maker for Jim Henson’s television productions. Largely self-taught, he transitioned into the art world following a collaboration with painter Paula Rego at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1996. British collector Charles Saatchi soon championed his work, commissioning Dead Dad (1997), a three-foot sculpture of Mueck’s deceased father. The work featured in the landmark exhibition Sensation: Young British artists, propelling him onto the international stage.

His reputation was further consolidated at the 2001 Venice Biennale, where the colossal sculpture Boy attracted widespread attention. Since then, critics have occasionally dismissed his work as overly literal or lacking conceptual rigour. Yet Mueck’s practice arguably draws more from pre-modern sculptural traditions than from twentieth-century modernism. His figures recall the emotional intensity of classical Western sculpture – the Madonna, the Pietà – works intended to elevate the spirit. Writing in the National Gallery of Canada’s Vernissage magazine, former director Pierre Théberge likened Mueck’s achievement to that of seventeenth-century sculptors such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini, noting that true virtuosity transcends surface realism to access ‘the life inside the shell of human beings’.

That sense of interiority is palpable with Dark Place (2018), where a colossal male face emerges from a cavernous black void. The haunted expression draws viewers inward, only to repel them moments later, as if sustained engagement risks emotional overload. By contrast, the newly commissioned installation Havoc (2025) marks a departure in both material and tone. Created using three-dimensional printing, this pack of wild dogs lacks the intricate surface detail of Mueck’s human figures. Instead, their snarling jaws and aggressive stances generate an atmosphere of threat, gesturing towards collective anxieties – violence, instability, and the erosion of social trust.

Throughout Encounter, Mueck’s sculptures feel uncannily alive. They are not merely technical feats but vessels of imagined interior worlds. Viewers inevitably project their own memories and emotions onto the frozen moments before them. The exhibition’s title is therefore apt: each work summons an engagement between viewer and sculpture. Largely unmediated by excessive wall text or digital codes, the exhibition offers something increasingly rare – an unfiltered encounter with physical presence.

As curator Jackie Dunn observes, Mueck’s sculptures ‘return us to the bodily, immediate and present moment of shared physical space’. In troubled times, she describes this attention to affect and feeling as ‘an ethics of empathy’. Notoriously media shy, Mueck resists intellectualising his process, yet his work communicates directly and powerfully. Beneath the extraordinary surfaces lies a sustained meditation on what it means to inhabit a human body – its tenderness, its weight, and its inevitable impermanence.

Ron Mueck: Encounter continues at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until 12 April 2026.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.