Thin Skin

The current show at Monash University Museum of Art, Thin Skin, is notable as the largest institutional exhibition in Victoria dedicated solely to contemporary painting in nearly a decade. Presumably for this reason, there has been much logistical support from MUMA for the new exhibition. A quarter of the thirty-six works here are new commissions by MUMA for the exhibition, while others have been borrowed from interstate and international collections. That many of the international artists are based in England is unsurprising, given that the guest curator, Jennifer Higgie, moved from Australia to London in 1993, has worked in senior editorial roles at Frieze magazine since 1998, and been a judge for the Turner Prize.

Thin Skin though isn’t so much a survey of contemporary painting or the working through of a formal or historical argument. Higgie has instead assembled a freewheeling selection of works where the notion of ‘thin skin’ is intended to invoke a ‘liminal space’ between a series of oppositions; chiefly the space between figuration and abstraction, but also the space between life and death, the animal and vegetable, the individual and their environment, the conscious and unconscious, and within the body itself.

There are many highlights, including Peter Graham’s A Cave in the Mind of a Shadow: My Memory of Looking Upon Mantegna’s Rescue of Lost Souls from Limbo (2023). Emerging from an outline of the painter’s head, every inch of the large canvas is crammed with ghostly overlapping figures and speech bubbles in a Day-Glo re-imagining of the Renaissance original. Another highlight of the exhibition is English-Caribbean artist Denzil Forrester’s Spice (1997). Painted in shades of marine blue, it is an example of Forrester’s numerous portrayals of London dub and reggae clubs created since the early 1980s (he has only recently emerged from obscurity and received significant critical attention). It is an idiosyncratic reworking of Matisse and Gino Severini, with Forrester’s angular compositions and off-kilter perspective uniting figure and space in an architectural whole.

Higgie, though based in London, seems to have kept abreast with contemporary Australian painting, with some of the more interesting younger painters included here. There is Jelena Telecki’s Mirroring (2019), a full-length portrait of a mime staring into a mirror in a luminous non-space of tobacco yellow surrounded by a thin halo of pink and sickly green. Her work is charged with a psycho-sexual tension that recalls the coldness Luc Tymans or Gerhard Richter, and her preoccupation with fabric, latex, and leather is visible in the mime’s corduroy trousers of deep burgundy and a salmon pink skivvy. Another notable young painter included here is David Egan. His Welling Up Weekly Green (2023) is a strange tableau of his typical motifs: playing-card designs, flowers, and rosary beads (which double as cellular entities). Though Egan is an engaging colourist (he recently published a small book on the subject), this work is painted in a single shade of washed-out grass-stain green. Although I found this particular paitnting queasy – its giant, all-seeing eye staring out from the center a bit too probing – it is identifiably part of his distinct practice.

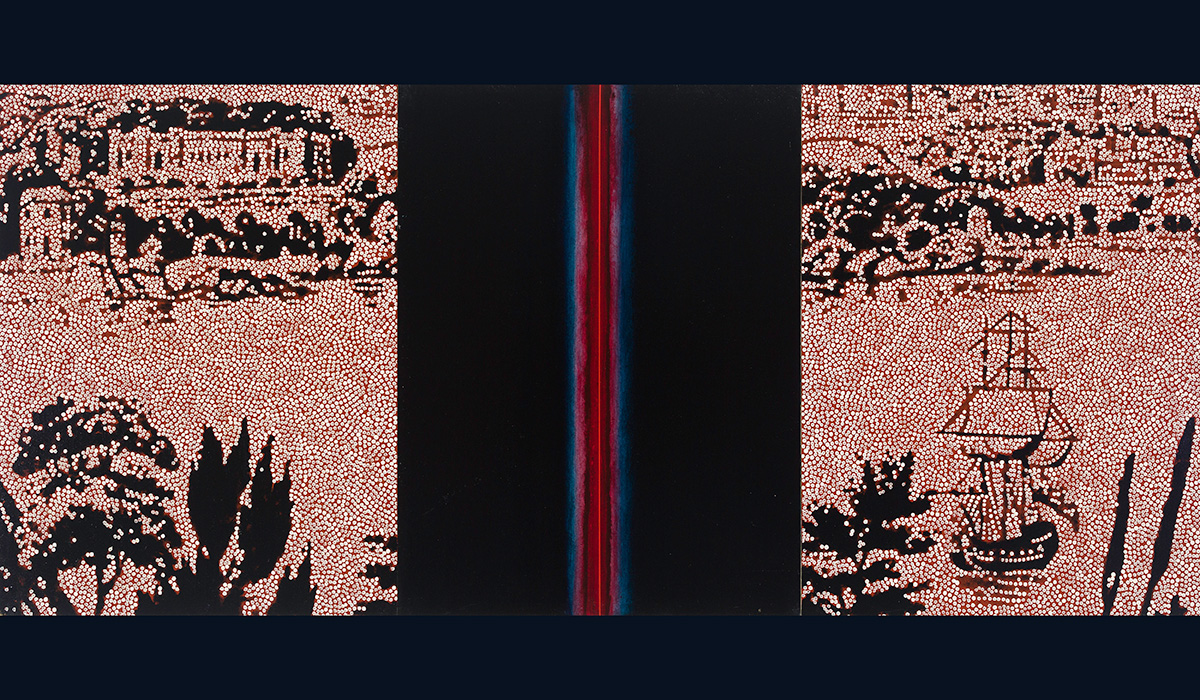

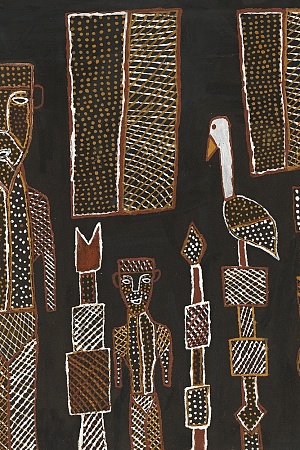

Gordon Bennett, Wound, 1990 (photograph by Christian Capurro).

Gordon Bennett, Wound, 1990 (photograph by Christian Capurro).

Gordon Bennett’s Wound (1990) is another highlight of the show. The three-panel work has an appropriation of Barnett Newman’s zip paintings flanked on either side by a colonial-era image of Sydney Cove where the neutral space is filled with dense, white Papunya Tula-style dots. Bennett’s painting is paired with Sidney Nolan’s Kelly at the Mine (1946), from his iconic Ned Kelly series. The alignment creates the most tension within the exhibition. Putting these two artists side-by-side – emblematic of post-modernism and modernism respectively, with their iconic treatments of Australian mythology – will always be generative. The tension is created by Bennett’s nationalist critiques and the visual correspondence between the two works. The Newman slit in Bennett is mirrored by Nolan’s Kelly, where a strip of red face peers out from a blank, black block (painted in enamel on board, the painting is surprisingly slick and inscrutable in person). Nolan’s painting echoes the three-part structure of Bennett’s; the centre of the latter is pierced by a huge arrowhead-like structure that dominates and divides both sides of the picture.

Considering the ambiguity of Higgie’s theme (doesn’t practically all painting now inhabit the ‘liminal zone’ between figuration and abstraction?), the exhibition, almost despite itself, does become something of a rambling survey of contemporary figurative painting. There are works such as those by Karen Black, Tracey Emin, and Tom Polo, whose freeness could perhaps only have happened after abstract expressionism. Their figurative elements are degraded as much by paint as by pictorial composition. There is ‘bad painting’ (Ellen Gronemeyer’s is-it-or-isn’t-it Chagallian kitsch of encrusted paint, Kieran Seymour’s cartoonish but menacing fantasies), fresh re-workings of modernism (Michael Armitage, Mitch Cairn, Helen Maudsley), and the unique, digital animation-like paintings of Tala Madani and Nick Modrzewski. The predominate sensibility that interests Higgie is a dreamy, slightly absurd form of the imaginary; John Spiteri’s free-floating extra-terrestrial classicism, Paul Becker’s fox cosily wrapped around an elegant lady’s neck like a serpent, or Tamara Henderson’s biomorphic vine trails.

The exhibition’s overarching theme of liminality sees the inclusion of works that are more strictly figurative. I still can’t decide to what degree Jenny Watson’s confident and controlled crudity or Mia Boe’s somewhat stiff appropriation of gnarled Drysdale-like figures qualify as constructive examples. The inclusion of an early painting by Rosslynd Piggott, Ten Rimbauds Holding One Rimbaud (1986), feels similarly tenuous, at least on formal grounds. A bleak neo-expressionist funeral scene, it is as if Samuel Beckett had designed a runway show for Comme des Garçons. Although these works are concerned with the space between city and suburbia, youth and adulthood, life and death and so on, the exhibition works best when the themes of liminality are matched by a formal slippage in the paintings. In these more figurative works it feels like the variety of concepts invoked in the exhibition is stretched too thin, but overall the approach of poetic evocation of oppositions and associations in Thin Skin is engaging. The paintings are connected by an overriding thread based in the realm of the sensible, and are treated as sensual rather than analytical objects. Despite my occasional itch for more antagonism or argument between the paintings, I appreciated being in a space where elusiveness rather than elaboration predominates.

Thin Skin (Monash University Museum of Art) runs until 23 September 2023.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.