States of Poetry Western Australia - Series Two

Series Two of the Western Australian States of Poetry anthology is edited by Kevin Brophy and features poems by Chris Arnold, Josephine Clarke, Lucy Dougan, John Kinsella, Edwin Lee Mulligan, and Annamaria Weldon. Read Kevin Brophy's introduction to the anthology here.

Taking on a transformation as an eagle and in that formation I was traveling within the cloud dust: and within the cloud dust there were small balls of lights. They were so small, as small as the smallest grain of sand. I myself was one of many divided as a matrix, scattered throughout and far reaches of the universe. We were all moving and weaving continually as if someone was making a dress out of stars.

And the more I knew about myself the larger an image I became. I looked over my shoulder. It was the universe. And looking back at the small ball of light that was small as the smallest grain of sand, I knew then really it was the size of our sun.

And the moral behind this story talks about the burning desire that burns within you that drives you to do the things you do! For me personally, I see mine every passing day of my life: the sun. It is also one of many scattered throughout and far reaches of the universe.

And when I sleep under the stars, as usual, I see so many of them that remind me that each individual has a burning desire that burns within them that drives them to do the things they do.

And as long as there’s a warmth that burns within it and rotates around the four corners of the earth, there’s a life that was given a purpose that comes in the form of human flesh. A gift of mortality.

Edwin Lee Mulligan

‘Sun poem’ was commissioned for the dance theatre production Cut the Sky (2015) by Marrugeku.

There’s two points of view about country, there’s a whitefella way of looking at country: seeing country as commodity, things they can take from the land and what they can make of it that can be useful. In my country there’s a lot of minerals. From diamond, gold, copper, oil, you name it. It’s all there for the taking. There is also uranium and gas. This country is very rich they say. But from an Aboriginal point of view there is another way of looking at country. The country dreams for her children.

For example gas ... the most desired mineral right now in the Kimberleys. For us she is a lady. She is part of our country’s richest mining deposit in Australian history. She’s a very rare expensive mineral that is highly toxic and a poisonous liquid substance hidden miles beneath us, within the Earth crust.

I’m going to tell you about this lady. Her English name is Valhalla, meaning the land of the dead. She is the most feared woman that ever walked the face of the earth. There were many stories that been foretold about this woman: stealing people from their sleep, possessing whole clan groups with silent death sleeps, leaving them to wake up into the spirit world, entombed in termite mounds for eternity.

They considered her to be very dangerous but to me, she’s like a mother. She’s been dreaming country. Dreams of ghost walking termite mounds in the distance through grassless plains.

She held my hand and walked me through country, speaking to the land and the land was listening. There’s a message being brushed up by the wind, her whispering words of burning grass dancing with tongues of fire.

When I stand on my spirit country, Ballil, I look down from the ridge. I see grassless plains where she once walked devouring innocent souls for her liking. We are continually warning people, even the hungry mining dog companies about a treacherous woman. She is poison.

Her name is Dungkabah (whisper)

Edwin Lee Mulligan

‘Dungkabah’ was commissioned for the dance theatre production Cut the Sky (2015) by Marrugeku.

Sleeping under a blanket, half asleep, I wrapped myself tightly, feeling the warmth after a cold night. I thought I was in a dream and wished it would be a good one. And as I spoke to myself about what this generation had to do with me, and the purpose in this life I’ve been given, all of a sudden I went into a deep dream. It happened so fast, it was like being sucked into a tunnel through a vacuum, Willy Willy, tornado and a twister.

My whole body went numb, paralysed. I couldn’t feel anything except the rhythm of my heart beating. As it beats it became louder and the louder it became the more heavily it weighed and the more heavily it weighed my spirit grew into a formation, becoming larger than a life image. My spirit transmitted, descending within the earth, and transforming into one of mother earth’s recognisable landmark monuments she created.

At that point I became gigantic and muscular, stretching for kilometres. In a way I had the earth in the palm of my hands. And looking at my hands I knew it was a symbol of great significance and high priority as an offering that was prepared for a celebration.

After that transformation to a dream I opened my eyes and what was before me left me breath-taken. I became a mountain overlooking vast flood plains. The ground was so fertile and rich having layers of minerals that were attached to my nerve systems, running with water and river. I became one with this earth. Pretty much like the blanket that I wrapped myself around that night but on a grand scale.

And then a voice I heard that spoke to me that felt encouraging to my spirit. The spirit of the land spoke to me, they said: Can you feel the connection to this land? I turned around under the gaze of my ancestors and softly replied ... exactly.

Edwin Lee Mulligan

‘Blanket Story’ was commissioned for the dance theatre production Cut the Sky (2015) by Marrugeku.

It’s been years and it’s never been raining, a sign of weather patterns at work in the creamy blue skies. An elder looked up and noticed a single cloud formation appeared. It was going towards a significant place. The cloud was very small and very dark and yet it still didn’t rain.

On this earth we walk the grassy plains with sun bleached sensitive skin sucked up by the heat, and with this temperature we too will weather away like a single insignificant blade of grass in the field.

Since the coming of time the spirits of the skies have been painting their pictures, telling the story of changing seasons.

They reached to the earth choosing individual vibrant colors to paint the universal giant canvas, calculating the mathematics of day and night, of rotating cosmos with our sun, stars and the moon, second by second in an endless equation.

An elder would say they’re singing our mothers’ land beneath our feet. We too will sing with them and yet our generation still walks on the grassy plains left alone wondering what this weather patterns means.

Edwin Lee Mulligan

‘Jimidilung’ was commissioned for the dance theatre production Cut the Sky (2015) by Marrugeku.

Once upon a time the crocodile was a human being. And then one day, one particular day his heart became hard and when his heart became harder, his flesh became hard and when his flesh became harder his skin became hard, and when his skin became harder it transformed into the scales on his back, deeply cut wounds that have never been healed.

He developed a taste for blood, he ripped open his stomach in a sacrifice. His own blood became cries of pain, floating debris of the past drifting on murky waters. He built towns and cities as a bandage to cover his wounds, leaving only a bloodstain to reveal his past. And then the crocodile says, ‘All Kingdoms are built by blood’.

The crocodile is a great hunter, a hunter of souls. Having the characteristics of a human being he is no different from a wolf in sheep’s clothing. And in the nature of the wolf he too walks on all fours.

Beware of murky waters and beware what lies below. There is a cunning creature that needs more than water to drink and more than a bandage to cover his scaly skin.

Edwin Lee Mulligan

‘Crocodile’ was commissioned for the dance theatre production Cut the Sky (2015) by Marrugeku.

Poet and painter Edwin Lee Mulligan was born in Derby in 1980. He is also known by his traditional name, Warrda Lumbadij Bundajarrdi. He grew up in Yakanarra and now resides in Noonkanbah in the central Kimberley and in Broome. His grandfather Jimmy Pike is a well-known Walmajarri artist and is the reason why Mulligan embarked on a career in the arts. Mulligan’s work has been exhibited in New York, Melbourne, Berlin, Rotterdam, and Perth. Edwin joined Marrugeku for the dance theatre production of Cut the Sky (2015), for which his poems in ABR’s States of Poetry anthology were commissioned. Edwin’s work was selected to feature on specially made WA police uniforms and police vehicle wraps as part of 2017 NAIDOC Week celebrations. Recently Edwin received the Shinju Matsuri 2017 Aboriginal Art Award for his ‘Seasons – Sharing Country’ work.

Poet and painter Edwin Lee Mulligan was born in Derby in 1980. He is also known by his traditional name, Warrda Lumbadij Bundajarrdi. He grew up in Yakanarra and now resides in Noonkanbah in the central Kimberley and in Broome. His grandfather Jimmy Pike is a well-known Walmajarri artist and is the reason why Mulligan embarked on a career in the arts. Mulligan’s work has been exhibited in New York, Melbourne, Berlin, Rotterdam, and Perth. Edwin joined Marrugeku for the dance theatre production of Cut the Sky (2015), for which his poems in ABR’s States of Poetry anthology were commissioned. Edwin’s work was selected to feature on specially made WA police uniforms and police vehicle wraps as part of 2017 NAIDOC Week celebrations. Recently Edwin received the Shinju Matsuri 2017 Aboriginal Art Award for his ‘Seasons – Sharing Country’ work.

Poems

'Sun Poem'

Further Reading and Links

Edwin Lee Mulligan's Associate Artist profile on Marrugeku

Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency profile

'Dreamcatcher' by Alex Smee from I Am An Artist. I Come From The Bush Series 1, ABC Open

I went where she reigned

far underground, deeper

than roots, in rooms hollowed

by hand and bone, where curved walls

contained my breath like lungs.

Passageways opened onto chambers

honeycombed in stone

where there was no light

and blind air read my skin.

Who painted the womb-shaped

echo-chamber with ochre veins?

The spirals on concave walls seem

to move with sound waves, fluid

as amniotic water, persistent as blood.

So far down, this far back, definition

fades. We braille a truth, one version

from things only guessed at.

In bone-dug bethels where perhaps

they incubated dreams, a woman

sleeps. In my palm, earth to earth

I hold her double: a small, clay statue,

rotund buttocks, fall of ample breasts

all luxuriant volume, prompting again

the old question: is she diviner or divine?

Annamaria Weldon

While women scanned the horizon, fishers

and hunters tended their nets, someone

etched the Lapwing crown-plumes in clay.

Abandoning hunger and

its frozen ground, they soar

South with the Grigale wind

Middle Sea harbingers of the

Lampuki-fish moon, its halo

a herald of autumn rains.

Outlines, incisions quicken those

plovers’ flight through terracotta sky.

A ghost flock, timeless on stone.

Annamaria Weldon

We met at the Neolithic display. I was staring

at the loom-weights, suspended in a glass case.

Handcarved stones, smaller than seashells

a tell-tale hole bored through their middle. That’s when

I noticed you, uncanny yet not out of place

holding a loom-weight. You seemed at home with fibre

your fingers felt its tensions, slack or taut,

sensitive to texture, strong hands threading

the weft, sinews familiar with the shuttle’s path

muscle memory of when to hold and release.

Back, forth, you weaved row after row, as friction sloughed

filaments of flax, infusing the hut’s dim light

with motes that clogged your lungs; each year

you strained harder and harder for breath. What

sustained you, arms aching as they bent and stretched,

shoulders lifting and lowering to the music

of your tuneless harp? Did your eyes sting?

Could you close them sometimes in that dark,

give yourself to the reverie and bridge the cleave

in time where we met, staring at those loom-weight stones,

handcarved and smaller than seashells, a tell-tale hole

bored through their middle. Suspended in the glass case

they have never stopped telling your story. Spellbound

I found myself called back by their slight shapes

by the weight of memory you left behind.

Annamaria Weldon

Alabaster: such a beautiful word for silence.

Neolithic Venus, was translucence eloquent

enough when stone was our mother tongue?

Yellow-throated crocus were strewn

at your feet, they fed you honey

and broad beans. Worship swelled

your breasts and fertile belly, men lived

without weapons, women were weavers

and potters crowned in cowrie shells

at death and in time their whitened bones

dyed red, with precious ochre

the blood of second life.

When survival required human milk,

herbalists were doctors and spirals holy signs,

hysteria a gift, fecundity revered

you were honoured as mother of the world

incarnate and neither clerics nor sceptics mocked

our fealty to the sacred feminine.

Annamaria Weldon

Annamaria Weldon’s writing residency with Symbiotica UWA prompted the poems, essays, and photographs of Yalgorup National Park in her last book, The Lake’s Apprentice (UWAP, 2014). She has just completed her third poetry collection, inspired by Malta’s Neolithic temple culture. She researched and wrote during several visits to her birth island, most recently as 2016 Writer in Residence at St James Cavalier Centre for Creativity, Valletta. Annamaria’s previous collections were The Roof Milkers (Sunline Press, 2008) and Ropes of Sand (Associated News Malta, 1984). Her poetry has been published in Australian literary journals, anthologised, broadcast on Radio National, and has been staged in several collaborative projects including contemporary dance and art installations. Her awards include the inaugural Nature Conservancy Australia Essay Prize, the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, and a shortlisting in ABR's 2016 Peter Porter Poetry Prize.

Annamaria Weldon’s writing residency with Symbiotica UWA prompted the poems, essays, and photographs of Yalgorup National Park in her last book, The Lake’s Apprentice (UWAP, 2014). She has just completed her third poetry collection, inspired by Malta’s Neolithic temple culture. She researched and wrote during several visits to her birth island, most recently as 2016 Writer in Residence at St James Cavalier Centre for Creativity, Valletta. Annamaria’s previous collections were The Roof Milkers (Sunline Press, 2008) and Ropes of Sand (Associated News Malta, 1984). Her poetry has been published in Australian literary journals, anthologised, broadcast on Radio National, and has been staged in several collaborative projects including contemporary dance and art installations. Her awards include the inaugural Nature Conservancy Australia Essay Prize, the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, and a shortlisting in ABR's 2016 Peter Porter Poetry Prize.

Poems

'in the National Museum of Maltese Archaeology'

'Hypogeum of Hal Saflieni, Malta'

Further Reading and Links

Archipelago, sleeping goddess whose body

we trample as tourists take selfies, bored lovers

seek mystery, stray dogs piss on temple stones.

Inside the sanctuary walls, torba floors endure

their bone-white ground broken as the silence

now deities are curios, gift shop souvenirs.

Asphodel and Sea-squill bloom in the corners of ruins

strewn like footnotes to remind us these shrines

are still alive. At dawn on the Solstice, an entry fee

is our only offering. Careless crowds block the portal

so the sun’s first beams can’t touch the holiest stone.

A child making a wild posy is chased by a man in uniform.

Annamaria Weldon

*torba is the Maltese word for hard plaster-like material made by the repeated pounding and wetting of several layers of Golbigerina limestone dust; it was usually spread over a rubble foundation for making temple and hut floors).

the text read:

Kissing you under an umbrella in rain

makes my list of favourite things;

a lunch crowd streamed around us.

we, dry in a cylinder,

sealed with that old golf umbrella’s

nylon night sky far from city lights –

I don’t recall why I didn’t walk you.

maybe the rain put its hands in pockets,

whistled east on Murray Street.

you left behind the scent of magnolia,

powder on a dark blue suit –

cheek relief on my shoulder –

foundation print on flax that escapes

authentication – a recollection I’ve kept

from the yellowing hands of sunlight, time and air.

Chris Arnold

you opt for form over colour

makeup smudged lenses

pale bare planes by the lakes;

a cygnet ellipsis in black

parenthetical necks;

white sky reflected in high water.

we sit where I have stayed

and watched an oak open and close –

green again – the bench

suspended on ampersands.

Chris Arnold

excerpt from Ligature

he drops his shoulders

lets out his breath

finds himself benched

between green wood slats and

a black plastic platter of sushi,

disposable sticks in his hand.

ache on his right eye like a river stone

thinking like five hands

at the piano. city stratified in front

his eye’s diameter

curves the park – half-moons grass

before his brain corrects,

sets it back flat beneath

palms pines poinsettias

that trail over asphalt;

ocean wind in

the river is busy

seems to flow back

toward the valley

as if behind its face

it replayed a moment

– something misspoken –

over and over

hoping the minute

were different.

he empties his breath

and says stop

the sound of her name

a song that doesn’t budge,

contains less

sound without her.

he begins. on the hill

he should turn right

but thinks of his chair

pinboard partition

the stench of lynx in the men’s

and walks forward:

North until the rail bridge

lifts him stops at its peak

as cars pass under: aluminium slab

and pantograph

hide passengers

sat silent still

as the city speeds beneath

Chris Arnold

excerpt from Ligature

her office kept cold

she shivers exhales

but never the satisfaction

of seeing her breath

a red-black plaid blanket wraps

her legs pattern

reminiscent of red dust picnics –

she’d pick spinifex spears

and snap them against

thumbnails pressed together

stalks shorter and shorter before

they refused her halving –

her rug synthetic soft

not the wire-like wool

that scratched her legs

through picnic dresses

in this somewhere her parents

she guesses – mouths

eyes hands closed

– locked postures unfigured,

only stone layered red on red

and green blades

she bends her back

sets weight against

arms on a white workbench.

Eyes focused close,

she slides steel between

eye blue slats

of a dragonfly’s thorax.

sinks pin into paper

and corkboard beneath;

sits straight

exhales again and thinks

this isn’t orthetrum caledonicum –

a holotype filed from light

while hers had paused

in still and cicada song

wings flat on acacia

Chris Arnold

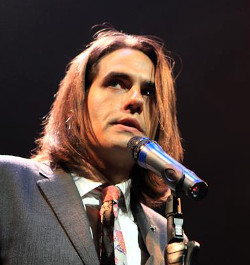

Chris Arnold lives in Perth and used to work as a software engineer. He was published in Westerly’s first writers’ development program, and now works as the journal’s web editor. In 2017, Chris commenced a creative PhD at the University of Western Australia, where he is combining his background in programming with poetic composition. He aims to produce a narrative for hybrid print and electronic reading, and is working, at the time of writing, with generative text and audio.

Chris Arnold lives in Perth and used to work as a software engineer. He was published in Westerly’s first writers’ development program, and now works as the journal’s web editor. In 2017, Chris commenced a creative PhD at the University of Western Australia, where he is combining his background in programming with poetic composition. He aims to produce a narrative for hybrid print and electronic reading, and is working, at the time of writing, with generative text and audio.

Poems

'pinned'

'derailed'

'&'

Further Reading and Links

Uneven Floor: Six poems by Chris Arnold

'compression artefact' by Chris Arnold in Westerly

I am a dickhead in ways I thought I wasn’t

I am a dickhead in ways people who call me a dickhead can’t imagine

I am a dickhead in ways people who call me a dickhead can imagine

I am a dickhead with residues and hangovers of misapplications of beliefs

I am a dickhead whose interior was an adequate backdrop for exterior worlds

I am a dickhead who has tried to leap synaptic gaps to make conversation

I am a dickhead who in damning his past and his routes via heritage has liberated

none

I am a dickhead despite the awareness of the dickhead moves that preluded me

I am a dickhead who has secretly thought I am no dickhead and that I am defying

the paths of dickheadery I was injected with at school and by the state

I am a dickhead who lives and breathes the pollution I condemn and tries to hang

onto life like my life is precious

I am a dickhead caught in anaphora because the mantra is preservation and

conservation and forests still fall and bush is scraped back to bare bones

I am a dickhead whose epiphanies and self-doubts would liberate him from the

damnation of exploitation and Western subjectivity

I am a dickhead for allowing the mining industry any leverage over my life at all –

I use implements manufactured using their extractions, their abominations

I am a dickhead for not planting enough trees for using petroleum products

I am a dickhead for deploying manners as a token of respect when I sit uncomfortably

in a roundtable confab, adding my two cents’ worth

I am a dickhead for utilising and being part of a monetary system I despise

I am a dickhead for saying I need downtime like everyone else – there’s no time free

and when I fall into the lush up-currents of birdsong it is not enough

to say I am there, nothing in the absolute bliss of existence, as existence

is so tenuous and the deprivation of the right to a spiritual journey

for all living things nullifies the luxury of my own journey towards

enlightenment

I am a dickhead because I once thought sex was a natural process, was more than a social

construct, was a sharing on an equal footing if there was consent, as if consent

was chained by the privilege of gender and identity

I am a dickhead because I don’t think of my pacifist rage as a form of violence, and caught

in the paradox, critique each step I take with motifs of calm to channel my anger

I am a dickhead because I am prepared to give up my life in an effort to stop damage to

other lives – peace at all costs, my body crushed by machinery on the edge of a

forest – trampled down by the military, the constabulary, neo-Nazi Australian

patriots flying their Southern Crosses and Eureka Stockade t-shirts, the Liberal

party, the Nationals, the right wing of the Labor Party, and some of the ‘left’

I am a dickhead thinking my words might make a difference and the problem is not

in the make but the kind of difference words can bring because words

can’t be contained and controlled and nor should they be, surely? Which leaves

me with what at the end of the day? as the tradies say as I co-opt to my purpose.

I am a dickhead because I have so immersed myself in the consequences of self and what

constitutes the ‘I’, especially my responsibility to my own subjectivity

and the declaration that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction

platitude which I don’t see as a platitude nor as just another variation on self-

mythologising which is an affirmation of purpose when I too am nothing in the face of

remorseless entropy and eschatology

I am a dickhead who won’t be held accountable when ‘the reckoning’* comes, comrade

I am a dickhead you might think is actually trying to call himself a dickhead to avoid

actually being called a dickhead or to say so while believing he’s not

but I can assure you I know the truth of it, and I am a dickhead

I am a dickhead who confronts people destroying the bush and throwing a tantrum

collapses as his heart falls out of sinus rhythm and brings the world of nature

he has constructed down around his ears

I am a dickhead who can’t ward off the truth with a mantra as the bulldozers and heavy

mining machinery are hauled slowly and steadily to the mines of the north

with vast areas of bush falling to blade every day and the roadside vegetation

vanishing despite a change of government as there’s no halting the loathing

and though there are many good people working to stop it, the hatred of life

beyond self and family permeates this world this dickhead is part of this world

this dickhead watches and dies a little more each day as he experiences and yet

cannot stop the ravaging the rapacity the cruelty of ‘development’ so what more

can a dickhead do than declare himself than plead dickheadery?

I am a dickhead who talks too much in a place where ‘lippy bastards’ like me are held

in contempt and I have the healed fractures of nose and skull, the cigarette burns

and the psychological scars to evidence this fact though my saying so makes

me more of a dickhead. Maybe you have to have lived here. Though that in

itself is no proof as the hearsay, voting trends, main street of town, actions

of land owners, and internet chatter will tell you

I am a dickhead who thinks he can in some small measure co-exist with the state he rejects

when the state murders and robs and bullies every nanosecond of its existence

while feigning innocence while claiming the higher moral ground while claiming

it speaks with the approval of the majority

I am a dickhead who thinks the majority doesn’t and shouldn’t rule that only consensus

has authority and a dickhead for whom authority is a lie anyway

I am a dickhead who thinks democracy is about oppression of minorities and not liberty

for all – never has been never will never wanted to be

I am a dickhead who won’t use pesticides or herbicides or fungicides but who lives

in a realm where they rain down from neighbours and shires and farmers

and contractors with the support and affirmation of multinational companies

that are eating the earth to its core and claiming they make the world go around

I am a dickhead who doesn’t think any job is better than no job. Not even worth

explaining that – a condescension that makes me even more of a dickhead

I am a dickhead because school mates, teachers, police, government ministers, right-wing

newspaper columnists, blokes in the pub, some friends and some exes, people

yelling at me as I march and protest as I read poetry in public, tell me so. Oh,

and some literary critics. Maybe more than some. I am not sure how that ‘more

than some’ sits in the calibration of the personalised (‘wank’) of the dickhead scale

I am a dickhead because I am loved by my son and my partner and my mother and my

brother and my mother’s partner and my auntie and uncle and cousins and maybe

a dozen friends. Which is not to say they might not privately think I can’t be

a bit of a dickhead on occasions but I am hoping against hope that they

can cope with that and it’s not simply out of politeness. What I appreciate

is their tolerance of dickheads, and I’d like to think I’ve got a bit of that as well

John Kinsella

*This is a reference to a communist marcher at a protest in Cambridge telling me that if I didn't convert from anarchism to communism, my fate would be decided at 'the reckoning'. – JK

Grasshopper on the window, the flyscreen, and stepping out

into the beige heat, over us. Tangled in our hair, hooked to our backs.

Grasshopper, cod wisdom. Grasshopper contraband on the eye-

out for plagues. The Australian Plague Locust and its tendency

to shift character when gathered together. In worship. In parliament.

O phase polyphenism, in which morphology and social disposition

shift. And the ag department would repeal their identities, make

mass hate an organophosphate reality. But the green, all the green

we make in the loving monocultural fields will be stripped away.

But it’s post-harvest, almost, and the wheat ears and canola pods

have been beheaded. The granaries are full. Nuseed Monola

worshipped in the holy of the holies. But then, as day cauterises

night, the Gould’s Wattled Bat retreats into its hollow, chatting

with others in its quodlibet way, illustration of the glories of sound

in the boombox valley. Grasshopper activates, and hops past

the early crickets and katydids. I read to the boy Keats’s ‘On

the Grasshopper and Cricket’, only distantly relevant, and I read

to myself Volcán: Poems from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua

published by City Lights which was still radical in 1993, with Alejandro

Murguía’s plea in his introduction to American readers: ‘who could

act directly to stop the flow of military personnel and weapons ...

Those right-wing death-squads. That anthology thirty-three years ago.

Fables. La Fontaine. Grasshopper on the event horizon. And so many

of us here in a state of mumchance, locked in our anachronistic language

of debauch and abuse. In this age, this rise of global fascism. Beware

the Australian Plague Locust – native! The temerity of its Latin name,

the prejudice of its Wikipedia manifestation (‘significant agricultural

pest’), that first swarm recorded in the east, out of the east, 1844.

Prophecy. Francis Bacon thought so little of prophetic texts. Cut

to fit. And its grasshopper shape. Its colouring. That chiasmus of thorax,

that art we lock & load. I don’t know, Grasshopper, I don’t know.

I lack wisdom to render you unto discourse. Even to make you

as Biblical as you deserve. Holy text of annihilation. And now,

indoors, we watch you disperse, alone. Observing your solipsistic

truths. Your personal ontologies. Can I repeat what I heard

you saying to each other? ‘I don’t know, sister, and neither do you.’

Seemed wise. In the beds the nymphs will stir, awake to the poisons

then no more. The world is there to be fed. Worldly as we are. Mondanité.

And so ‘little difference’, or maybe so hard to tell, between locust

and grasshopper. And those swarms we must watch out for,

those swarms fought back with legislation, with a thesaurus of death.

John Kinsella

We are thrilled to find evidence of roos returning –

after being driven out of the reserve and slaughtered

by hunters, the survivors are finding refuge at Jam Tree Gully.

The vestiges of the old mob. And maybe new mob driven

this way by hunters down on Victoria Plains. In the long grass

they hide. They make tracks and graze and flatten

areas for rest. They are maintaining out of sight.

I walk with Tim at a tangent to the house, up towards the north-

western granites. The grass is long and wild lupins have built

a platform and it’s a hidden area now with hungry reptiles

waking. Haven’t seen a snake yet, but just today I found

the burrow of a bungarra – could tell by the patterns

of digging, by the flicked dirt, by the slender reptilian scats,

by the fresh brown dirt divined and fomented inside the hill.

A few days ago, the first bobtail we’ve seen since

the days grew long enough. And sun skinks! The awakening.

And today, I forge a way through the grass, up and across,

and Tim follows in my wake, cautious, cautious. We don’t

walk the roo trails because, I say to Tim, The chance

of kangaroo-ticks is higher in those avenues, in those

boulevards, in their town squares. And, what’s more, they

have their town-planning, their architecture, their road-

work to respect – temporary is never less in its design,

its purpose. With pollen Op-arting our clothes, with

honeyeaters chasing each other to the four corners,

we are inside something beyond our design, and that’s good!

Spenser wrote of the ‘carcass examinate’, and before roos

showed themselves here again, before the bungarra

worked its burrow, before the nests came thick

and fast in trees around the house, and before we knew

for sure that the tawny frogmouths have territory

marked up by the red shed, we could not be sure

that the destroyers of land – omnipresent – hadn’t

succeeded, hadn’t wracked life from the body examinate.

John Kinsella

It rained heavy, ridiculously heavy, when the heat

was at its peak, and then it went dry – the ebb & flow

of the surface-water, the water soaked deep. It’s

thin-on now, even vanished. A dry creeping towards

longer cold nights. The tank is down to 20 000 litres,

or thereabouts. And no clean air for weeks, as farmers

have burnt their tinderish stubble to ash, so volatile

the flames have mostly escaped, or been let go, to erase

‘shade trees’ in paddocks, and bush that has stuck

for legal reasons only. Fire, the trickster? It’s agony

to watch as we choke, eagles spiralling higher.

And the mistletoe birds are easing off, chasing those sticky

fruits on other hillsides. All that sunset collusion in the red

chest of the males – flashy, unexpected. But we notice

the females as often – no hierarchy of glory for us, though

they have their own codings, their own headrushes. But

while they were here, skipping unisex from mistletoe to mistletoe,

we were as ecstatic. And now at dusk, writing in dying

light, I sign off on almost four years of twists in the senses –

yesterday we heard a ‘new’ bird, and Tim found it singing

in the south-east corner of the block. A fantail cuckoo.

This map that won’t reveal the secrets. Try following it.

Between these poems there have – of course of course –

been many others. Those of lost trees, and damaged wetlands.

Of animals crushed and extinguished. Of wars and conflict.

The emulsion of sinews and xylem and phloem. The fencers

who in the name of work! take out as much bush as they can

to lay down new posts, those stretches of taut wire.

All of that. Proximity, and in the catchment of our days.

And reports from further afield. The boats turned

back on the high seas – the drownings we no longer

hear of inland, just a couple of hours drive from the sea.

All of those closed doors. All those birds that won’t fly again,

as once farmers killed mistletoe birds in their droves,

arguing that in doing so they were saving the native bush

they’d clear the following week, month, year, decade.

All of us in this temporal lapse – unique, trying to breathe,

take in the beauty, filtering contagions we release ourselves.

John Kinsella

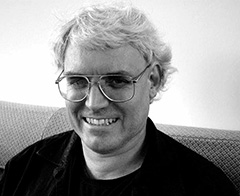

John Kinsella’s most recent volumes of poetry are On the Outskirts (UQP, 2017) Firebreaks (WW Norton, 2016), Drowning in Wheat: Selected poems 1980–2015 (Picador, 2016), and the three volume edition of his Graphology Poems 1995–2015 (Five Islands Press, 2016). His poetry collections have won a variety of awards, including the Prime Minister's Literary Award for Poetry and the Christopher Brennan Award for Poetry. His volumes of stories include In the Shade of the Shady Tree (Ohio University Press, 2012), Crow’s Breath (Transit Lounge, 2015), and Old Growth (Transit Lounge, 2017). His volumes of criticism include Activist Poetics: Anarchy in the Avon Valley (Liverpool University Press, 2010) and Polysituatedness (Manchester University Press, 2017). He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge University, and Professor of Literature and Environment at Curtin University. With Tracy Ryan he is the co-editor of The Fremantle Press Anthology of The Western Australian Poetry (2017). He lives with his family in the Western Australian wheatbelt.

John Kinsella’s most recent volumes of poetry are On the Outskirts (UQP, 2017) Firebreaks (WW Norton, 2016), Drowning in Wheat: Selected poems 1980–2015 (Picador, 2016), and the three volume edition of his Graphology Poems 1995–2015 (Five Islands Press, 2016). His poetry collections have won a variety of awards, including the Prime Minister's Literary Award for Poetry and the Christopher Brennan Award for Poetry. His volumes of stories include In the Shade of the Shady Tree (Ohio University Press, 2012), Crow’s Breath (Transit Lounge, 2015), and Old Growth (Transit Lounge, 2017). His volumes of criticism include Activist Poetics: Anarchy in the Avon Valley (Liverpool University Press, 2010) and Polysituatedness (Manchester University Press, 2017). He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge University, and Professor of Literature and Environment at Curtin University. With Tracy Ryan he is the co-editor of The Fremantle Press Anthology of The Western Australian Poetry (2017). He lives with his family in the Western Australian wheatbelt.

Poem

'Detracking the Body Examinate'

'Graphology Endgame 100: I am a dickhead'

Further Reading and Links

Mutually Said: Poets Vegan Anarchist Pacifist - A blog shared between poets John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan

for Lorraine and Tony

Not an expression of wealth but one of quiet desperation,

the heat and dry eviscerating hope – a giant shadehouse

of green cloth, and an above-ground keyhole

swimming pool, with avocadoes and ferns edging

the cement slabs, aura in the midday twilight.

And the red dust, too fine to shut out, decorating

the aqua-emerald waters, a wound open from an attack

of the inland leviathan, invisible as the filter strains

to remove impurities, leave pure as chlorinated amniotics,

and the dry birds squawking to be let in – shriek-caw-shriek.

Inland pool that was no waterhole, gnamma parody

down from the salmon gums and wandoos and pepper trees,

looking out over the sheep paddocks, the pig yards,

down onto the rat-tunnelled horse dam, out beyond the white-

walled house-dam of fated sailings, edge of the earth.

And this was in the Seventies, long before the rise

of pools on cocky properties, a nod towards a strong

swimmer, towards a childhood visiting the coast, a father

who loved the ocean. But there was a mother too, one

of the goldfields women who never learnt to swim.

Wheatbelt swimmers, wheatbelt pathfinders,

wheatbelt paradoxes carted in on the truck in riveted

steel cubes, brimming from standpipe flow; and then lesser

but regular cartings for ‘topping-up’. Record the volume,

pay up later. And all those kids travelling from far

afield, travelling to take a dip, frolic beneath the shadecloth

cathedral, bathe in the gothic font of swimming pool –

Australian crawl, breaststroke, frog-kick where the sun

denies the existence of amphibians, and dirt looks past

the sky for an opening through which rain might fall.

John Kinsella

Josephine Clarke

Landscape photographs from Black Saturday by John Gollings

Fremantle Arts Centre, July 2015.

enter a room and find stripes of night on each of the walls

pines have been hushed

black trunks block the light sky

and underfoot the ash is soft, waiting for wind

there can be no name for this

letters and numbers in degrees

of requiem so many points

of a pin where the fire spirit chose to go

a doorway into another room where undressed,

old hills roll in wrinkles

trees like stubble

on anatomy we don’t normally see

roads like a lover’s tracings

on flanks, shoulders

camera is a word for room in another language

– this is a tender lens

how do we forget

the defence of bark

how a hill names a track

the requirement of sun for shadow

photographs on a wall

paper

scissors

rock

Josephine Clarke

A version of 'Aftermath' was published in Westerly’s online edition: New Creative, September 2016.

– Dwerda Weelardinup

The whistle of the djidi-djidi on the army tank

slices the evening grey. Someone

is walking their dog. I am walking me

around this once defensive hill.

Gun House, Rifle Cottage. Cantonment.

Embers of a campfire through the scrub.

Quarried and tunnelled

– gradient constantly resettled.

At the Gunners’ Cottages,

new stair-rails gleam like epaulettes.

Reticulation runs on rolled lawn;

sand escapes across the footpath.

This hill is knotted with histories

the locals have long fought to keep alight.

What’s left is still

a glassy view of river and sea.

Cars sew a thread of lights across the Swan;

stop-start exhausts rumble at the red

beside an octopus with arms of rubber –

mural on the Navy Stores.

Djidi-djidi makes his

djidi-djidi sound. The lights turn

green; brake lights extinguish

one by one.

djidi-djidi – wagtail

Josephine Clarke

– photograph 1964.

at the bridal table

in front of Mill Hall stage

she is small

and tight lipped flowers

from somebody’s garden

in a bucket behind her head

the shell of her jacket

loose

as though she has been

deflated

her chest an empty cavity

all that sheen –

hat, suit

damask on the table –

cannot mask the weather

of another century

traced across her face

another hemisphere

hangs in gold hoops at her ears

in the primavera of her growing

great iron cannons

to the East of the Valtellina

blasted a chorus for her nightmares

la prima guerra

cast that strong jaw

her straight stare

did she choose not to understand

the photographer’s request

for a smile?

Josephine Clarke

we remembered

your face, pink, lit like we’d never seen it

when your hands at your shoulders met his

for the Pride of Erin

the ease of your gliding

for the three-four Modern Waltz

that marquisite brooch on the bodice

of your teal best dress

your stepping in perfect union on the dance floor

– how ineluctable your coupling

you could never forget

that quick step to expecting

the slow drive to Harvey

to tell your father, an internee,

or the nuns who sang you a full Mass

despite the rule of the Church

we watched

the slow unravelling

dinner to the dogs

chips of china in the wood pile

tears in the cold wash house

behind the steaming copper

we eavesdropped

on the soft vowels of dialect

with your allies when he was out

magari ... I wish

che pu fa? ... what can you do?

your laughter rippling

a corrugated scale by the end of the pot

we will never forget

you had to ask for money

he always asked what for?

at the end you called him

he sat by you his gaze adrift

you had fought each other hard

but stayed

till the end of the dance

Josephine Clarke

Josephine Clarke grew up in the South West of Western Australia, the daughter of Italian migrants. After gaining an Arts Degree and a Dip. Ed. at the University of Western Australia, she taught English at high school before travelling to other states and countries with her family. Josephine has had short stories and poetry published in Cordite, Westerly, indigo, Eureka Street, and the Review of Australian Fiction. She now lives in Fremantle and is a member of a collective that organises monthly poetry readings for Fremantle Voicebox, and has been actively involved with Out of the Asylum Writers’ Group, based at the Fremantle Arts Centre.

Josephine Clarke grew up in the South West of Western Australia, the daughter of Italian migrants. After gaining an Arts Degree and a Dip. Ed. at the University of Western Australia, she taught English at high school before travelling to other states and countries with her family. Josephine has had short stories and poetry published in Cordite, Westerly, indigo, Eureka Street, and the Review of Australian Fiction. She now lives in Fremantle and is a member of a collective that organises monthly poetry readings for Fremantle Voicebox, and has been actively involved with Out of the Asylum Writers’ Group, based at the Fremantle Arts Centre.

Poems

'Nonna'

'harbour'

Further reading and links

Cordite Poetry Review - Josephine Clarke

For my mother

The young men,

friends of our middle one,

camp nights in your bed.

Some leave it with hospital corners,

some leave it like a lair to revisit

and some make cocoons on top.

In most cases

they are shaping up.

On kitchen raids

they all report sound sleep

and I wonder what it is

that breaches their dreams

as they lie down

in this last contracted room of yours?

Can they imagine your life?

Is it the patina of photos, letters, legend –

all that dense action –

that guards their rest?

I wish for an instant

that I could share with them

my montage of you:

the stout baby with black curls,

the girl smiling with her shoulders hunched

at the Southern Ocean,

the young doctor tending

someone in an iron lung;

and sometimes our mother,

simply our mother,

in the garden,

white glints in the air,

flowers that have floated off your dress.

And now abrupt Trojan old age.

No, they don’t see it.

They can’t.

But part of this is what keeps them

coming back, I think,

that and the allure of your

strange come-and-go arrangements.

At fifty-one

I’m thankful

for every second

you have been away

and shown us all

that there is still life

to be lived

beyond convention.

Lucy Dougan

In crisis

I go to the local library

and do not take out

the book I find,

this one or that one first,

what matter?

Outside beside my car

sits a strange chrome and vinyl seat,

part of a vanity set,

stranded, hieratic, ruined,

like the beautiful straight-backed

low seated chair-people

of Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche.

I do the visual maths.

Will it fit behind?

– no, there, rightfully, is the seat for our grandson –

I consign its odd allure to my phone’s photo bank instead.

I sit on it only once,

open its cream frayed seat

with its tooled insignia of promise

– nothing –

What does it mean

for home to be a failure?

What does it mean

for other places to be a failure?

I leave the throne to its own

mise en scène, neither

desolate nor replete

were I to claim it.

There is, after all, no mirror

in front of which to place it

though I fix my hair and do my lips

before I reverse away.

Lucy Dougan

The old cat and dog

now sleep in our room

in an uneasy truce

between the floor and bed.

It is as if they are not sure

the house exists

once we no longer light it

or move about it,

once we lie down

in agreement it is night.

It’s come to sit on my chest,

their Stilnox camaraderie,

and when I wake in snatches

I have thought different things.

Perhaps we are at sea

and this is our cabin

or perhaps without quite knowing

how or why

the rest of the house is demolished,

its surfaces wrecked, its innards divulged

in a fuselage of darkness.

Mornings are a strange venture.

As I keep night for them,

so they – treading out first –

herald in the day for me.

Lucy Dougan

The girl on a rug with a cat

is an entirely decorative proposition.

She curls, the cat curls, even the rug

displays some notion of this movement

with its diverting curlicues.

Life, too, is making a start inside the girl

although she cannot know this right now.

Some contract with another is being made,

even as we speak, on the rug with the cat beside her.

The striped ginger cat grows its hairs.

It is not the cleverest cat.

Somewhere some time a worker,

who cannot be revealed in this schema

but who nonetheless has left a signature of sorts

in all the curlicues, made the rug.

They weren’t paid well.

Perhaps they got by.

Were they a girl with life beginning inside them?

And did they own a cat,

perhaps a goat, or duck or a pig?

In this scene a lot remains unknown,

just as it always does.

Lucy Dougan

I lie on the couch

like a beaten dog

as Philip Mould advances

on his latest art forensics

and there are these absolutely

free and liberated daubs

of greens and browns

in close-up on the screen.

They are of the earth

in a surprising and counter way

to all that sateen, country houses,

rich people by the yard.

And from my beaten dog pose

I potentially fall in love with Gainsborough.

How could I have not before?

Philip Mould’s suit combos are impeccable.

He is always consulting experts,

always moving crisply through the

weak light of investigation sites

– the galleries – but his eyes

look infinitely tired

as if he has done so much

looking for us.

I trust his close-ups.

After enough experts

and trailing about,

there is Gainsborough again

with his louche letters,

and unsympathetic wife,

his treatment of waistcoats

and his small garden tray arrangements

that look touchingly a lot

like the moss tray gardens

of childhood

only more elaborate

with water features

and places to arrange a nymph or two,

a satyr.

They are a step up from what one

could get at the model shops,

though proximate, small feathery trees

and a brittle feeling of those bags

full of fake glittering lawn.

It leaves me unaccountably sad

that Gainsborough had to live with someone

who threw out all his dirty letters.

What a loss Philip Mould’s prim sidekick

says off guard, says passionately,

as the camera hovers over the tray garden

– this little grave of creativity –

and she’s right.

Lucy Dougan

Lucy Dougan’s books include White Clay (Giramondo, 2007), Meanderthals (Web del Sol), and The Guardians (Giramondo, 2015), which won the WA Premier's Book Award for Poetry in 2016. She holds a PhD from UWA on representations of Naples. She currently works as Program Director for the China–Australia Writing Centre at Curtin University.

Lucy Dougan’s books include White Clay (Giramondo, 2007), Meanderthals (Web del Sol), and The Guardians (Giramondo, 2015), which won the WA Premier's Book Award for Poetry in 2016. She holds a PhD from UWA on representations of Naples. She currently works as Program Director for the China–Australia Writing Centre at Curtin University.

Poems

'Your Bed'

Further Reading and Links

Lucy Dougan's ABR contributor page

Cordite Poetry Review - Lucy Dougan

Curtin University staff profile - China-Australia Writing Centre

Poetry, in ‘stilling things’, as Martin Heidegger suggested in 1950, is nevertheless always restlessly active. These six voices are six stills from a fast-moving history of poetry in Western Australia. They are evidence that poetry can provide moments we can enter into in suspended silence while experiencing that movement and agitation so essential to important poetry.

Ben Lerner, in The Hatred of Poetry (2016), might be right in suggesting that the poems of ‘our moment’ are always about to fail us, but I guess for those of us interested in stilling things (and here there are echoes of William Carlos Williams), it remains important to know about things through poems, and to know poems as things.

I don’t know how different Western Australia is from the rest of Australia. I don’t even know whether there is one place called Western Australia. I suspect there are many Western Australias, and it will take many anthologies to get anywhere near a comprehensive ‘picture’ of the range of places Western Australia is. This 2017 selection is not representative of anything beyond itself, but it is also, I hope, a very Western Australian experience for readers. Each poet seems to me to represent certain aspects of the State, but also, and more importantly, each one is a voice stilling things in response to living in our moment.

Edwin Lee Mulligan (Warrda Lumbadij Bundajarrdi) works from Broome in the far north on its mangrove coastline, and is also from Noonkanbah in the Kimberley – a land once farmed by pastoralists into devastating erosion, and only won back by its Indigenous owners after nine years of legal battles. Knowing this, it is possible to connect to the stories he tells of dreaming regeneration into the land from beneath a blanket under the stars at night. His story of the crocodile participates in a long history of oral storytelling, and in the deeply human desire to find meaning, even enigmatic meaning, in the figures and events we witness in nature. Mulligan’s stories soar as jagged in front of us as those eroded cliff faces, termite mounds, and volcanic cores do throughout the central Kimberley. My conviction is that these stories need the presence of an audience. You have that role to play here. I hope you visit them and can stand still inside them.

From the southern reaches of the state, John Kinsella, fresh from his epic Graphology project (Five Islands Press, three volumes, 2016), adds to this selection a more intimate and wistful tone than we are used to from him, but still a voice that embraces Aboriginal history and Indigenous prior claim; and while pointing the finger at (for example) white destructive farming practices, he announces these as examples of the ways we all avoid truth, avoid thought, avoid responsibility, and most of all avoid lyric presence in our environment. The way he celebrates the visit of a small, rare bird nearby is something. His riff on the grasshopper revives and revises a creature that maybe offers itself as doppelgänger, mirror, scapegoat, and even an emblematic figure that should be on the State’s coat of arms. Mostly, though, I want you to read his ‘I am a Dickhead’ poem for the distinctive and unforgettable contribution it makes to Australian poetry of political protest infused with dry wit. It’s not just Western Australia that needs such a voice.

Lucy Dougan, editor of the 2016 WA States of Poetry anthology, and herself a prize-winning poet, brings the intensity, cultural savvy, and churn of big-city culture to her poetry. She too, though, is in the business of stilling things, as her superb series of meditations in The Guardians (Giramondo 2016) has shown. I trust her close-ups. Her girl on a rug with a cat is as ekphrastic as anything, so much so that the poem seems to be all picture until we pay attention to the tones sparked and carried by the line breaks. Just as in The Guardians, and in all poetry where there is room for the genuine, Dougan brings our attention to the forgotten, the cast-off, the easily ignored objects, images, memories, and animals around us. Western Australia has a world-class poet on its hands in Lucy Dougan.

Josephine Clarke is here as someone familiar to the Perth poetry scene, but nationally a new voice, and one that comes at us with a powerful opening poem that is an uncompromising portrait of a marriage at its best and worst. In relatively short free verse lines sometimes scattered on the page, Clarke picks her way through the details of experiences so deftly that you can’t be sure how she has arrived at those vivid effects and frightening ideas.

Chris Arnold is another emerging poet. His poems are mostly parts of a longer narrative sequence. In ‘Derailed’, you do feel the rails of a rhythm that would make it difficult to change one word of the poem as it descends through the page and follows a series of events dictated by a city landscape and a set of motives we can, at this stage, only guess at. There is nothing predictable or less than observant and thoughtful in each phrase and idea. I expect that this is poetry hard won from many drafts, poetry that will reward further visits because there is much to notice if one can be still with it.

Annamaria Weldon is an experienced mid-career poet whose work is poised, fresh, and confident. These poems are from a manuscript in preparation. Many poems in the developing collection are inspired by Maltese temple culture dating from the Neolithic period (5,000 BCE). Growing up in Malta, Annamaria Weldon rambled among these ruins as a child, years before they were listed as world heritage sites (temple offerings now replaced by entry fees, as she notes in ‘Goddess we trample’). She has been in Australia since 1984, and it was in Australia that she became aware of the land holding within it many ancient sacred sites. Annamaria Weldon revisited her childhood sites during an artist’s residency in Malta in 2016. Her poems approach the knowledge that these temples were there at a time that was before-writing – that they existed in a sense as the texts of their time. What is it that a Neolithic alabaster Venus is saying to us?

All in all, I am excited by the poetry given a showing in this small anthology. I think it speaks to diversity, sophistication, music, landscapes, and the engagement of Western Australian poetry with our moment.