Poetry

Peter Steele once described his teaching and writing as ‘acts of celebration’. He is – and was – quite literally a celebrant: in his role as a Jesuit priest, and as a poet of praise. Those acts of celebration extend to his prose works as well, both his homilies and his literary essays, especially those that take up the matter of poetry. Peter Steele passed away, after a long illness, in June of this year, but not before his latest offering was presented at a book launch he attended the week before he died and a few days after he received a national honour. Unable to speak, he had his brother read a list of five major concerns that animated his poetry and which he looked for in others: ‘Imagination; learning from experience; fascination with experience in all of its many forms; the world imagined in a different way; and earth and spirit interlocked.’ This new book, of eighteen essays and six poems, bears out those concerns, establishing his voice among us in a kind of afterlife, not of fame, but of familiarity, someone we might turn to, that is, as an intimate or a familiar.

... (read more)Stephen Edgar shows us the dazzling pleasures of poetry that is ‘strictly ballroom’. Some years ago in a Greek restaurant, I was having lunch with Edgar, Martin Harrison, and Robert Gray. My fellow diners began excitedly discussing the finer technical points of a range of verse meters ...

... (read more)Apollo in George Street: The Life of David McKee Wright by Michael Sharkey

David McKee Wright is a curious figure in Australian poetry – and in New Zealand poetry, for that matter. As editor of the Bulletin’s Red Page from 1916 to 1926, he was a well-liked and -respected figure in his own time (1869–1928), but he has seriously faded since. He is thinly represented in a number of anthologies, both here and in New Zealand, and was omitted altogether from Robert Gray and Geoffrey Lehmann’s anthology Australian Poetry Since 1788 (2011).

... (read more)Australian Poetry Journal Volume 2.1 technology edited by Bronwyn Lea

Australian Poetry Journal, the biannual publication published by Australian Poetry, offers a national focus for poetry and criticism. It includes contributions from established writers and from new voices. All in all, APJ indicates a cheering and cohering centre of gravity for all things poetic in contemporary Australia.

... (read more)Selected Poems 1975–2010 by Ken Bolton & Four Poems by Ken Bolton

Ken Bolton has published twenty books of poetry in the past thirty-five years, including a verse novel, The Circus (2010), and an earlier Selected Poems (1992), as well as seven often hilarious poetic collaborations with John Jenkins. An art critic, Bolton edited the seminal magazines Magic Sam and Otis Rush; and he has been a publisher with Sea Cruise and Little Esther Books. Bolton’s poems amusingly undermine any sense of affected certainty or closure – ‘with none of the confidence / of Samuel Johnson, // with none of the élan of Frank O’Hara, / with only a guilty and apprehensive grin // because in part / I belong to the school that says // if you see a leg pull it // I begin this tour of my attitudes ...’ (‘Lecture: Untimely Meditations (Tentative Title)’). Rather, his work is buoyed by indeterminacy, in which a blithe surface both collapses and embodies intellectual enquiry, most apparent in his spacious, extended poems, but also in more descriptive ones, such as ‘Kirkman Guide to the Bars of Europe’, from Sly Mongoose (2011), and one not included here, ‘Happy Accidents’, which unravels his influences. ‘Perhaps my oeuvre in / large part represents / a slur on the poetry of my betters – / whose example / allows me to go wandering off, / by the reeds, ankle deep / in mud, / mumbling inconsequently – / somehow ‘licensed’ by them, / by their example – / though heedless of it?’ (‘Poem (Up Late)’).

... (read more)Michael Farrell was the 2012 winner of the Peter Porter Poetry Prize, awarded by this magazine. open sesame is his latest collection of poetry, and an earlier version of it won the inaugural Barrett Reid Award for a radical poetry manuscript, in 2008. It has 123 pages.

... (read more)As a result of the public works of Puncher & Wattmann, it has been established yet again that a book of poetry can andshould combine meaning and design in a shock of pleasure. Toby Fitch’s first full-length collection, especially the central title poem, does this in spades. Orpheus returns to ...

... (read more)Wild Card: An Autobiography 1923–1958 by Dorothy Hewett

Dorothy Hewett’s Wild Card: An Autobiography 1923–1958 was first published by McPhee Gribble in 1990. Now, a decade after Hewett’s death, UWA Publishing has reissued this extraordinary autobiography in a beautifully packaged, reader-friendly format. Reviewing Wild Card for ABR in October 1990, Chris Wallace-Crabbe drew attention to Hewett’s candour in relating explicitly her many sexual experiences. He noted that the sexual self – so often elided in autobiographies – is on full display in Wild Card, and made the crucial observation that for Hewett ‘sex is both somewhere beyond personality … and intrinsic to it’. As Wild Card makes clear, Hewett was an expressively sexual woman, but her sexual desires and experiences were inextricably part of her imaginative and political passions.

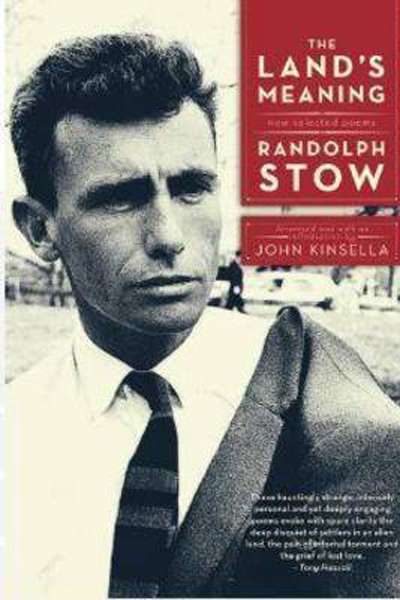

... (read more)Randolph Stow, who died in 2010 aged seventy-four, must now be considered part of the Australian canon, whether that concept is conceived broadly or as a smaller cluster of Leavisian peaks. This status derives from his eight novels, which include the Miles Franklin Award-winner To the Islands (1958), the celebrated children’s book Midnite: The Story of a Wild Colonial Boy (1967), the much studied The Merry-go-round in theSea (1965), and the book that many (including me) think his masterpiece, Visitants (1979).

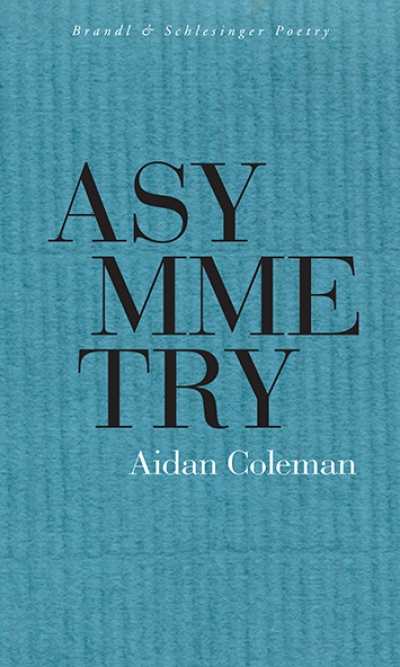

... (read more)In July 2007, at the age of thirty-one, Aidan Coleman suffered a stroke as a result of a brain tumour. Asymmetry is a book in two parts. The first details the poet’s survival after this near-death experience, his struggle to regain full use of his body and to speak and write again. The second part is a group of love poems for his wife, Leana ...

... (read more)