Non Fiction

As a freshwater ecologist, Alison Pouliot endeavours to understand the interplay of the processes that sculpt the Australian environment.

As an environmental photographer, she aspires to capture the intricacies and obscurities of these processes.

The insidious creeping nature of drought can sometimes lend itself more to images than words.

... (read more)Visions of Colonial Grandeur: John Twycross at Melbourne’s International Exhibitions by Charlotte Smith and Benjamin Thomas

Not many substantial private collections of art and decorative arts in Australia have remained intact from the nineteenth century. John Twycross (1819–89) was one of Melbourne’s early art collectors, and his collection has proved to be an exception. Twycross, lured there by the gold rush, made his money as a merchant in Melbourne in the middle of the nineteenth century. He began collecting art during the 1860s and became a major lender to the National Gallery of Victoria’s historic 1869 loan exhibition. He also spent heavily at the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880 and even made a few purchases from the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition of 1888, the year before he died. He was also a lender to the 1888 exhibition. Some 200 of the works that Twycross purchased at these exhibitions have remained together. In 2009 a descendant donated them to Museum Victoria, which is custodian of the Royal Exhibition Building.

... (read more)American Paul Dickson has written many books on aspects of language, including Words from the White House (2013). He also claims to have invented some fifty words, although he admits that only two of these have any real chance of becoming ‘household words’: word word ‘a word that is repeated to distinguish it from a seemingly identical word or name’, as in ‘a book book to distinguish the prior work in question from an e-book’; and demonym ‘a name commonly given to the residents of a place or a people’ (as Briton or Liverpudlian). In his new book, Dickson includes these two words, along with a solid collection of English neologisms from mainly English authors from Chaucer to the present. Such is the prerogative of the author of a book on authorisms.

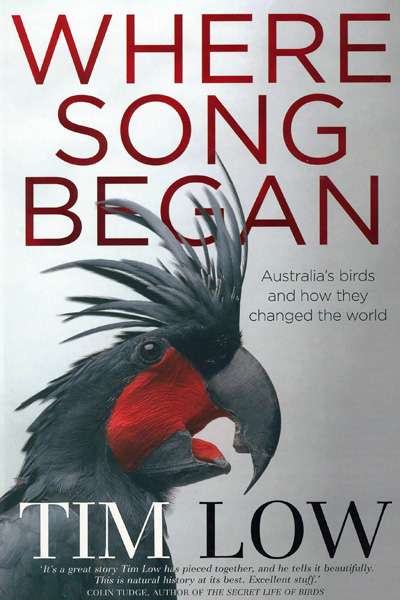

... (read more)Australia’s birds stand out from the global avian pack in many ways – ecologically, behaviourally, because some ancient lineages survive here, and because many species are endemic. The ancestors of more than half of the planet’s ten thousand bird species (the songbirds) evolved right here (eastern Gondwana) before spreading across the world. Indeed, Tim Low claims in this important and illuminating book that Australia’s bird fauna is at least as exceptional as our mammal fauna, which has such remarkable elements as the egg-laying monotremes (platypus, echidna) and our marvellous radiation of marsupials (kangaroos, quolls, bandicoots, possums, etc.). Can this be so? As a mammologist, my initial response was that Low’s claim is a bit rich, but, after reading this book, I take his point.

... (read more)The last photographs taken of Jean Galbraith show a wrinkled woman in her eighties, with wispy hair pulled back in a bun, wearing round tortoiseshell spectacles, thick stockings, and sensible shoes – the kind of person you might expect to see serving behind the counter of a country post office early last century, or pouring endless cups of tea at church fêtes. Yet her unprepossessing appearance belied the extraordinary woman within. For Australian nature lovers and botanists, Jean Galbraith was an icon. Over the seventy years of her writing career (her last article was published when she was eighty-nine), she turned botanical writing into an art form, branched into television and radio scriptwriting, wrote children’s books, lectured tirelessly on the beauty of Australia’s native flora, and became a fierce advocate for conservation. When she died in 1999, aged ninety-two, she had earned many awards and accolades, including the prestigious Australian Natural History Medallion.

... (read more)Smashing Physics: Inside the discovery of the Higgs boson (and how it changed our understanding of science) by Jon Butterworth

I must let you into a secret. I have three different ways of reading books: lightning fast, with serene attention; and, as with Smashing Physics, postmodern.

The fast mode is forced by unavoidable professional requirements. This week, for example, I received a (thankfully) slim volume just hours before having to record a satellite interview with the author who is based at Harvard. I had ninety minutes to skim the novel to obtain enough ‘feel’ for the work so that I could lead a credible discussion. All went well.

... (read more)Red Apple: Communism and Mccarthyism in Cold War New York by Phillip Deery

This book is about a moral panic resulting in the deployment of huge police and bureaucratic resources to ruin the lives of some unlucky individuals who were, or seemed to be, Communist Party members or sympathisers. None of Deery’s cases seems to have been doing anything that posed an actual threat to the US government or population; that, at least, is how it looks in retrospect. But at the time the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the FBI judged otherwise and saw them as dangerous anti-democratic conspirators pledged to undermine, if not overthrow, the state. (Does any of this sound familiar?)

... (read more)Flooded Forest and Desert Creek: Ecology and history of the River Red Gum by Matthew J. Colloff

In July 2009 I toured the Murray-Darling Basin and northern Queensland with a group of American college professors to see firsthand how the waterways of these regions were faring. By this time, south-eastern Australia had been in drought for nearly a decade, reducing its rivers and creeks to mere trickles. Aboard the MV Kingfisher, we explored the wetlands of the Barmah Choke, the narrowest section of the River Murray, where thirsty River Red Gums stood starkly exposed along its banks. Years without flood, as Chris Hammer observed in The River: A Journey through the Murray–Darling Basin (2011), was changing the Barmah ‘from a wetland to a woodland’. But the drought did break, eventually: twelve months after my visit the river flooded and the inundation of the region’s floodplains brought relief to the many species, human and non-human, for whom the Murray is their lifeblood.

... (read more)The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political leadership in the modern age by Archie Brown

A remarkable feature of the concept of political leadership is its apparently infinite elasticity: it stretches over presidents and prime ministers, dictators and popes, revolutionaries and reformers. Take the concept beyond politics, and its reach effortlessly expands to include business executives, platoon commanders, primary school principals, the captain of the cricket team, and many more. But is it useful, or even accurate, to describe all these figures as ‘leaders’ given they, and the entities they lead, have almost nothing in common? Are they really comparable as leaders?

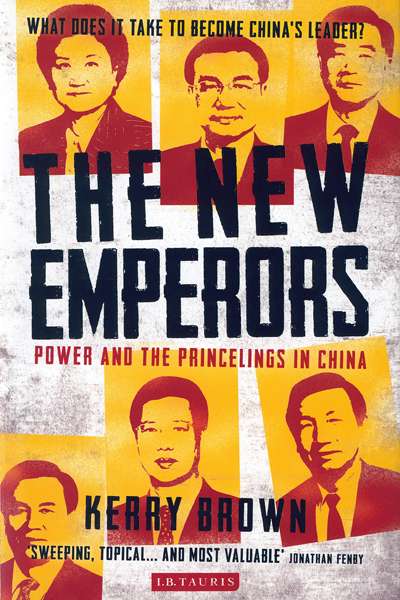

... (read more)The New Emperors: Power and the princelings in china by Kerry Brown

For countries, and none so important to Australia, have a political system as opaque as that of China. This is deliberate; since the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has striven to make turnovers in its leadership as bland as possible. But the elevation of the country’s current ‘Fifth Generation’ Leadership was actually full of drama. The New Emperors, written by Kerry Brown, director of the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, tells us why.

... (read more)