Non Fiction

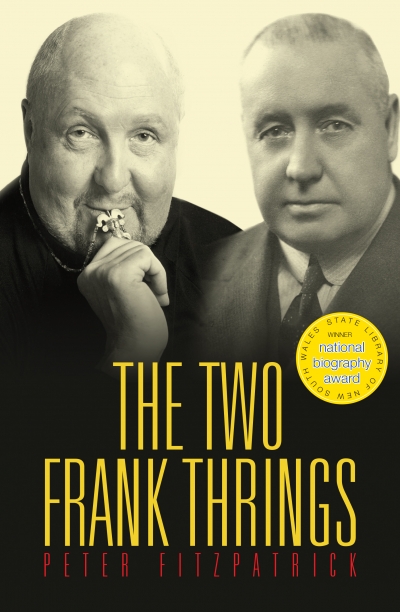

How lucky we were! My ‘baby boomer’ generation in Melbourne grew up on stories of the second Frank Thring (1926–94), which competed in outrageousness with the anecdotes we heard of Barry Humphries; and throughout the 1960s we had the opportunity – more so in the case of Thring, who had now settled back in Melbourne as a regular performer on stage and television, as Humphries began his lifelong commute to London – to catch both of these not-so-sacred monsters in the flesh and on their own home turf. (As I asked of the females of this species in a previous article in ABR – ‘Mordant Mots’, September 2007 – what is it about Melbourne that has produced such bizarre and brilliant creatures?)

... (read more)Wild Card: An Autobiography 1923–1958 by Dorothy Hewett

Dorothy Hewett’s Wild Card: An Autobiography 1923–1958 was first published by McPhee Gribble in 1990. Now, a decade after Hewett’s death, UWA Publishing has reissued this extraordinary autobiography in a beautifully packaged, reader-friendly format. Reviewing Wild Card for ABR in October 1990, Chris Wallace-Crabbe drew attention to Hewett’s candour in relating explicitly her many sexual experiences. He noted that the sexual self – so often elided in autobiographies – is on full display in Wild Card, and made the crucial observation that for Hewett ‘sex is both somewhere beyond personality … and intrinsic to it’. As Wild Card makes clear, Hewett was an expressively sexual woman, but her sexual desires and experiences were inextricably part of her imaginative and political passions.

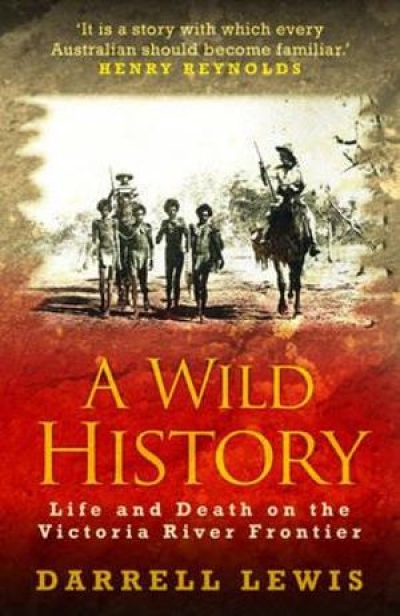

... (read more)A Wild History: Life and death on the Victoria River frontier by Darrell Lewis

Darrell Lewis first encountered the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory in 1971 when he worked as a field assistant for the Bureau of Mineral Resources. ‘There was an aura about the country which fired my imagination,’ he writes. Since then, as an historian and archaeologist, he has become an auth ...

It was David Marr who commented that the key character in Gore Vidal’s first memoir, Palimpsest (1995), was not Jimmie Trimble, the boy whom Vidal loved when they were at school and who died, aged eighteen, at the battle for Iwo Jima; nor Vidal’s blind and adored maternal grandfather, Senator Thomas Pryor Gore, whom young Gore would lead onto the floor of the Senate; nor his life partner of half a century, Howard Auster; not even the audacious and polymathic Gore himself. The star of the book was in fact Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, who was dying when Vidal began to write Palimpsest.

... (read more)Thinking the Twentieth Century by Tony Judt, with Timothy Snyder

This author, this book, and its composition are all extraordinary. Tony Judt, one of the most distinguished historians of his generation, made his name with studies of French intellectual history, then in 2005 he published his masterwork, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. ...

... (read more)Soon after the announcement of the shortlist of this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award (‘the Miles’), bookmaker Tom Waterhouse installed Anna Funder’s All That I Am (2011) as favourite. Fair enough, too: it’s an astute and absorbing Australian novel about, among other things, Nazism’s long shadow. But Waterhouse favoured Funder – oddly – because her non-fiction book Stasiland (2003) won the Samuel Johnson Prize in 2004. He asserted – debatably, even if it proves correct in 2012 – ‘a strong positive correlation’ between the Miles and the Australian Book Industry Awards. Most interestingly, he noted that the administrators of the Miles, The Trust Company, have now authorised the judges to extend their interpretation of Australianness beyond geography.

... (read more)Newspapers, they say, are in the throes of ‘far-reaching structural change’, a euphemism for ‘extinction’ that arouses complacency in the breasts of the e-literate; fury in those of the technophobes. But one only has to take a slightly longer view to realise that the golden age of newspapers, over which Creighton Burns presided as editor of The Age, may have only ever been a transitory phase.

... (read more)Rupert Murdoch: An Investigation of Political Power by David McKnight

It is a thought-provoking photograph. In 1988, during the bicentenary of The Times, Rupert Murdoch and Queen Elizabeth are pictured sitting at a news conference within the inner sanctum of the London broadsheet. Mogul and monarch are at arm’s length – she, straight-backed, legs crossed, hands gathered together above her lap; he, leaning forward and slightly to his right, towards her, with a piece of paper pinched between thumb and forefinger. Behind and between them, pinned to the wall, is what appears to be a photograph of Prince Charles crossing the road holding the hand of a very young Prince William.

... (read more)All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939–1945 by Max Hastings

It is a brave undertaking to write a single-volume history of World War II. As Max Hastings notes, we already have many good books in this category: Weinberg, A World At Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994); Calvocoressi, Wint, and Pritchard, Total War: The Causes and Courses of the Second World War (1989); Millett and Murray, A War To Be Won: Fighting the Second World War (2000); and Hastings might have mentioned Parker’s Struggle For Survival: The History of the Second World War (1989) and Ellis’s Brute Force: Allied Strategy and Tactics in the Second World War (1990). He was too late to notice Andrew Roberts’s latest contribution.

... (read more)I first discovered Australian literature in Argentina. While I was there studying Argentinian literature at the University of Buenos Aires in 2009–10, I spent many nights hunched over the table in our dingy kitchen with one of my housemates, Teresa. We would pick over the politically infused vernacular of the short stories ...

... (read more)