Literary Studies

Whose Place?: A study of Sally Morgan’s My Place edited by Delys Bird and Dennis Haskell

The first thing to be noted about this collection of essays is that it is aimed at a quite specific market – HSC/VCE students. There is a list of ‘Study Questions’ at the end, and the language of the essays is consistently pitched at an upper secondary school level. Readers who want more complex responses to My Place would be better served by consulting the eclectic bibliography to the text as a starting point.

... (read more)John Hanrahan reviews 'A.D. Hope' by Kevin Hart, 'James McAuley' by Lyn McCredden, 'Peter Porter' by Peter Steele, 'Reconnoitres' edited by Margaret Harris & Elizabeth Webby, 'Annals of Australian Literature' edited by Joy Hooton & Harry Heseltine

Oxford University Press has begun a welcome series called Australian Writers. Two further titles, Imre Salusinszky on Gerald Murnane and Ivor Indyk on David Malouf, will appear in March 1993, and eleven more books are in preparation. Though I find the first three uneven in quality, they make a very promising start to a series. In some ways they resemble Oliver and Boyd’s excellent series, Writers and Critics, even being of about the same length. However this new series is less elementary, more demanding of the reader. It is, predictably, far sparser in critical evaluation, concentrating on hermeneutics, and biographical information is as rare as a wombat waltz.

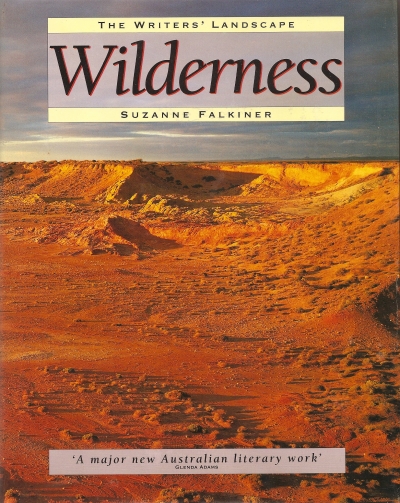

... (read more)Wilderness: The writer’s landscape, volume I by Suzanne Falkiner

Suzanne Falkiner’s Wilderness is a garden of delights. This is one of the most imaginative, innovative, and useful books on Australian literary culture to emerge for some time. The book represents the first volume of a two-part series entitled The Writers’ Landscape, and Wilderness traces the influence of Australian landscape on Australian writers.

... (read more)Boundary Conditions: The poetry of Gwen Harwood by Jennifer Strauss

In Boundary Conditions, Jennifer Strauss, taking her title from the Eisenhart poem of that name, points to the centrality of Gwen Harwood’s concern with ‘those littoral regions where the boundary terms that define themselves on either side of us also overlap and interact'. It is here, she claims, that ‘our most intense experiences, for better or worse, occur, and it is here that she correctly and perceptively locates Gwen Harwood’s major preoccupations as well as her recurrent images and settings.

... (read more)He described himself as a ‘no-hoper’ (he died in a mental hospital in the poverty of his poetry and Catholic faith). These days, the label ‘a poet’s poet’ is sufficient to scare off anyone interested in approaching a body of work that is both substantial and challenging. With the publication of this annotated collection, containing most of Webb’s known poetry and extracts from his verse dramas, it is just a little dispiriting to see Webb’s work acquire a whiff of canonical sanctity. A short, cautious introduction by the editors Michael Griffith and James McGlade concludes with the respectful praises of five eminent Australian poets, as if a show of hands from the panel of distinguished experts were enough to explain anything of the enigma of Frank Webb to someone coming across his work for the first time. I think he deserves more. In an age where packaging plays such a conspicuous role, it is time to rescue Webb from the shrine of Tradition and to make an effort towards attracting new readers to a poet who magnificently defies idle curiosity.

... (read more)‘No,’ Ania Walwicz said at the Melbourne Festival when asked if she was an ethnic writer, ‘I’m a fat writer.’ We laughed and applauded.

The multicultural professionals, however, may not let her (or Tess Lyssiotis) off the hook so easily. I have in mind that small but eloquent band of people, usually from institutions, who actually have a vested interest in keeping constructs like Anglo-Celtic/non-Anglo-Celtic, English-speaking background/non-English-speaking background alive and functional.

... (read more)Pen Portraits: Women writers and journalists in nineteenth century Australia by Patricia Clarke

About ten years ago, I was asked to give a talk to a Sydney group of Australian writers. (Actually, they asked Leonie Kramer, but she was busy.) I decided to talk on ‘Some unknown Australian women writers of the nineteenth century’ in ‘the hope of interesting some of them in researching the lives and careers of their predecessors.

... (read more)Patrick White by May-Brit Akerholt & Jack Hibberd by Paul McGillick

Although it is accidental that these two books have been released simultaneously (they just happen to be numbers two and three in a series of monographs on Australian playwrights) it’s a fortuitous accident. In form, they provide examples of two markedly contrasting and entirely appropriate methods of dealing with the work of a playwright. And historically, both Patrick White and Jack Hibberd have been landmark playwrights. Together they may well share the honours for the instigation of the most critical vitriol in the Australian press. At the same time, their work has always generated fervent praise and support from theatre critics, practitioners, and audience members who want theatre that is surprising, challenging, and innovative.

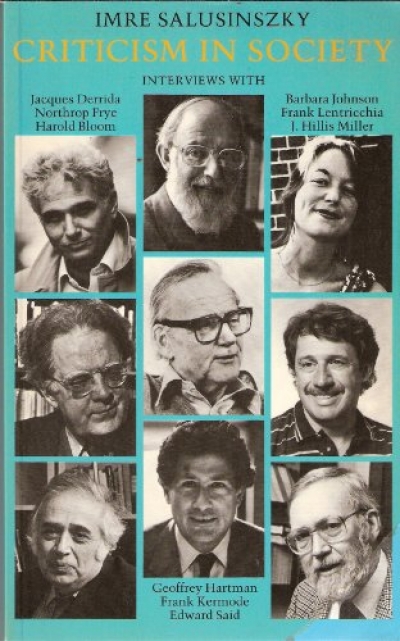

... (read more)Living with Stress and Anxiety is the title of one of those self-help guides put out by Manchester University Press in its ‘Living With …’ series; Living with Breast Cancer and Mastectomy is another. Living with Literary Theory is not a scheduled volume, I imagine, although some people who work in the lit. crit. business seem to regard literary theory as a prime source of anxiety for which the only remedy is theorectomy. In the decade since Terence Hawkes first taught us how to live with Structuralism and Semiotics (1977), Methuen has succeeded admirably through its expository ‘New Accents’ series (edited by Hawkes) in making it easier for everybody to cope with such anxiety-provoking processes as Lacanian psychoanalysis or Derridean deconstruction; too easy, in the opinion of those who them-selves feel uneasy at the politics of marketing criticism’s nouvelle cuisine as fast-food takeaways, with Methuen playing the role of the big M.

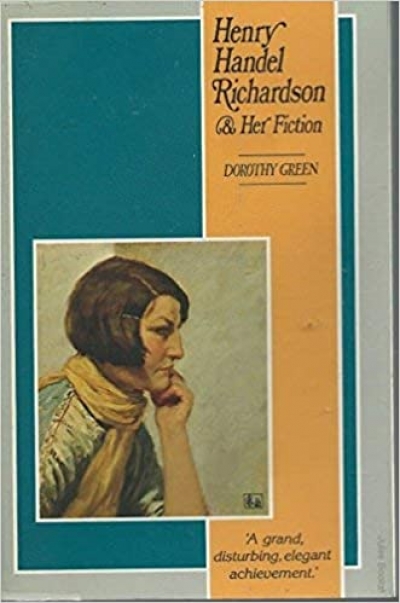

... (read more)Henry Handel Richardson and Her Fiction by Dorothy Green

Occasionally, there are books of literary criticism which stay in the mind’s eye, so to speak; they endure beyond the point of short-term recall: the central argument, the general impress of thought, the singular, illuminating ideas and catchments of insight. As with Dorothy Green’s massive and intense scrutiny of Henry Handel Richardson, these books have the authority of a kind of passionate clarity, even when they seem paradoxical, or odd.

... (read more)