History

Somebody recently told me that Geoffrey Blainey wrote much of the text of this history of Victoria while travelling in aircraft. If true, Blainey has an enviable knack of finding seats with elbow room, but otherwise there’s no reason to complain. Sir Charles Oman, the great military historian of the Napoleonic wars, was said to have drafted one book during a summer spent waiting for connecting trains at French railway stations. Those fortunate enough to possess a lot of intellectual capital should make the most of it. In the central four chapters of social history, perhaps the most satisfactory part of this book, Blainey cites his evidence as ‘the accumulation of years of casual reading of old newspapers, looking at historic sites and talking with old people’. Disarmingly, he adds: ‘Most of the explanations of why change came are probably my own’.

... (read more)Secrecy in human affairs seems to me as useful in grappling with problems as flat-earth dogma is in navigation. I have the belief that the most dazzlingly effective stroke the U.S. Pentagon could make toward dissipating nuclear nightmare would be to throw open the whole spectrum of its weapons experimentation and innovation to anyone who wanted to walk in and look it over. My further belief is that the sheer weight, variety and thrust of all that would be revealed would be such a horizon-expander to, say, Soviet scientists that those scientists would be too caught up in the sheer challenges to the understanding of it all to constrict themselves into any scramble to winnow out immediate military advantage – and indeed that the very process of assimilation of and adaptation to the revealed data would very likely have so many sorts of extraordinary and mutually beneficial (that is, both to the U.S. and the non-U.S. world) effects that the very reasons for nuclear confrontation would vanish from sheer irrelevance and inanity.

... (read more)The Commanders edited by D. M. Horner & War Without Glory by J. D. Balfe

These books have little in common though they are both concerned with men at war. Balfe’s book is chatty, idiosyncratic, episodic and without any academic intent. Often using the words of three pilots involved, he tells the story of the futile and costly air fighting which followed the highly successful Japanese attacks against Malaya, Sumatra and the Netherlands East Indies. Australian aircrew were forced to fight the Japanese with Hudsons and Buffaloes. Given that the enemy had overwhelming superiority in numbers; that the Buffalo was one of the worst fighters produced, and that the Hudson was no match for virtually any Japanese aircraft, the Australian squadrons after the initial contacts were almost completely destroyed. The causes of this disaster and the eventual outcome of it are well known.

... (read more)Anyone still worried about the military-industrial complex unveiled by Eisenhower at the end of his presidency can have their Angst updated with this disturbing book.

The present Republican commander-in-chief, with only the tinsel medals of Hollywood for his proud chest and a set role to play, is unlikely, even as a parting gesture, to use up prime time to let us in on how the robust infant of Eisenhower’s day has come of age and mutated with the times to become the fully-integrated military-industrial-academic-bureaucratic complex it is today.

Frank Barnaby, professor of peace studies at the Free University of Amsterdam and former head of the Swedish peace research centre, SIPRI, in the opening paper in this collection, ‘Will There Be A Nuclear War?, shows how powerful and well-entrenched this complex has become. Vast bureaucracies have grown up in the great powers to deal with military matters, and about 500,000 scientists, around 25 per cent of all scientists employed on research, work exclusively on military research.

... (read more)The Japanese tactics in today’s export war are identical with those they employed so successfully in 1941–42 against a bigger army than theirs in Malaya: they attack individual units ‘with surprise and with our strength concentrated’. This is one of the two leitmotifs of Russell Braddon’s book. The other is his notion of Japan’s ‘hundred years’ war’. During his years of captivity in Changi between 1942 and 1945, Braddon was told once by a Japanese officer: ‘This war will last a hundred years, Mr Braddon. I’m afraid you will never go home.’ Later, after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, when he was about to leave Changi, he passed a Japanese officer who was being escorted into the gaol. ‘In a spirit half of elation and half of spite I turned and shouted, “This war last one hundred years?” “Ninety-six years to go”, he called back; and neither of us bothered to bow.’

... (read more)In Carlton the graffiti’s already been around for months: ‘Oscar Oswald is right ... 1984’. Now even if you’ve never heard of Oscar Oswald you’ll know one thing about him and that is that he's not George Orwell ‘If Oscar Oswald is right in 1984,’ the graffiti might easily be saying, ‘then George Orwell must have had it all terribly wrong in 1949’.

... (read more)The Transformation of Virginia 1740-1790 by Rhys Isaac

In a recent issue of the New York Review of Books, Gordon S. Wood lamented the current dominance of ‘monographic history’, a dominance which he claimed has brought ‘chaos’ to the discipline of history. Most works, he argued are so specific and technical that they are comprehensible only to a few specialists in each field. The title of this book might suggest that here is yet another study designed only to appeal to that hardy little band of historians who spend their professional lives grubbing through the records of early America.

... (read more)Cutting Green Hay: Friendships, movements and cultural conflicts in Australia's great decades by Vincent Buckley

On his first day at St Patrick’s, East Melbourne, Vincent Buckley was ‘flogged and flogged’ by a Jesuit priest in ‘an incompetent fury’. It is an experience that many of his readers will easily recognise, though their remembered lambastings were more likely to have been incurred at the hands of the Brothers and, unlike Buckley’s, would have been a continuing feature of school life.

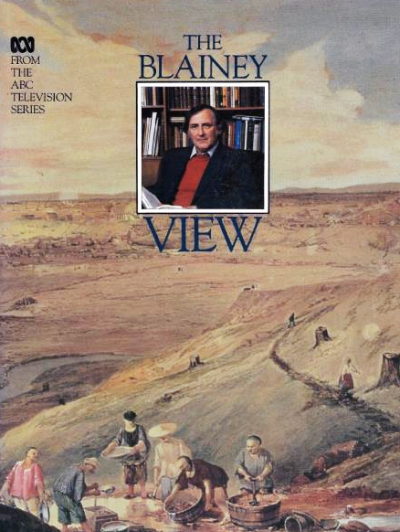

... (read more)Geoffrey Blainey must be Australia’s bestselling historian by a very long way. His audience is far wider than Manning Clark’s for instance: and far less critical. Clark is periodically savaged by packs so frenzied they often seem unable to recognise the nature of the quarry. The difference of course is a matter of both style and substance. Clark, as an early critic once said, is ‘full of great oaths and bearded like the pard’, and he has not changed his fundamental spots. Blainey’s picture is inserted in the barren landscape on the front cover of this book, all warm and friendly; not a Jeremiah, but a kindly tribal elder who will unravel your historical landscape sotto voce, and with perfect equanimity. You can step into your past with Geoffrey Blainey and know you’ll be safe. He’s just about the friendliest historian imaginable.

... (read more)W.F. Mandle reviews 'The Tyranny of Distance', 'Triumph of the Nomads', and 'A Land Half Won' by Geoffrey Blainey

Who, we wondered, gets the largest Public Lending Right cheque each year – Manning Clark or Geoffrey Blainey? Probably still Manning, and he’ll still be ahead in the royalties stakes too, but the younger colt must be closing fast, and he shows no signs of tiring. Even if he did, his publishers, like Manning’s for that matter, can always do, as they have here, a recycling and packaging job.

... (read more)