History

For many Victorians their impressions of the squatting age have been formed by visits to Como or to Werribee Park. These mansions, of course, reflect the ultimate achievement of the squatters’ aspirations but tell us little of the struggles involved in realising those aspirations. These tangible proofs of squatter opulence, coupled with historical accounts of the squatter-selector battles, have inevitably cast the squatters in the role of the ‘bad guy.’ But to Heather Ronald her squatters, the Chirnsides, are the ‘good guys.’ ‘I dispute the oft-repeated statement,’ she says, ‘that squatters set themselves up as a class above everyone else … Many of the earliest successful squatters came from good families and were educated people; their attitudes were moulded by the way of life in rural Scotland, with its Squire and tenant system … Thomas and Andrew, in their estate management, were only following the example set by good landlords at home.’ But this was precisely why many Australians opposed them.

... (read more)Unsettled: A journey through time and place by Kate Grenville

There has been, for some time, a debate among researchers of Australian history. Should the moral and psychological dimensions of settler experience be examined, or do we know enough already?

... (read more)Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions – How the people of Yirrkala changed the course of Australian democracy by Clare Wright

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions were intensely significant in Australian politics, contributing not only to major changes in race relations in Australia but to the way Australians understood their country’s history and its future. Clare Wright’s Näku Dhäruk is a lucid, accessible, and engaging account of those 1963 Yolngu1 Petitions from the Yirrkala region of Arnhem Land: her book will deservedly be read widely and throw new light on the complex events which shaped this turbulent time. Yet as powerful and moving as this book is, it will leave some readers with lingering questions. This review will outline some of its many strengths, and will also suggest some of those questions.

... (read more)Ned Kelly: A Pictorial History by George Boxall & The Kelly Years by Graham Jones and Judy Bassett

To borrow from Jones and Bassett: ‘Not another Kelly book!’ Well, yes; in fact two more can be added to last year’s bumper crop. One of them comes from Kelly Country itself, written by two local residents. And the two books provide a perfect example of the extremes in the Kelly publishing game.

... (read more)Venice: The remarkable history of the lagoon city by Dennis Romano

Venice is a vast project for an historian. Dennis Romano has written what he calls a ‘remarkable history’, generous in its pursuit over 600 pages, with eighty-five pages of impeccable documentation. It is a revisionary history, not only because Romano goes beyond the end of the Republic in 1797, when Napoleon conquered Venice and planted a Tree of Liberty in St Mark’s Square. The three chapters on Modern and Contemporary Venice bring Romano’s history to the present day.

... (read more)Lost Souls: Soviet displaced persons and the birth of the Cold War by Sheila Fitzpatrick

Many students of Australian history are aware of a particularly ugly cartoon published in the Bulletin in December 1946. ‘The Pied Harper’ depicted a hook-nosed Arthur Calwell playing a Jew’s harp welcoming a shipload of ‘imports’ (Jews) into Australia. This was the stereotypical image: bearded, unattractive, and similarly hook-nosed. The analogy with the legendary Pied Piper of Hamelin was clear. In contrast – and to assuage such public anxieties about mass migration – were the published photographs in January 1948 of Calwell, the immigration minister, celebrating Nordic-looking ‘beautiful Balts’, as he termed them, on their arrival to Australia.

... (read more)The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History: Second Edition edited by Wilfrid Prest

The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History announced itself in 2001 as ‘a landmark publication, the first such work of reference for any Australian state or territory’. This new edition, which adds entries, updates others, and lands with a thump at almost 200 pages more than the previous volume, is especially timely in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, which magnified awareness of the differences between the histories and cultures of the Australian states.

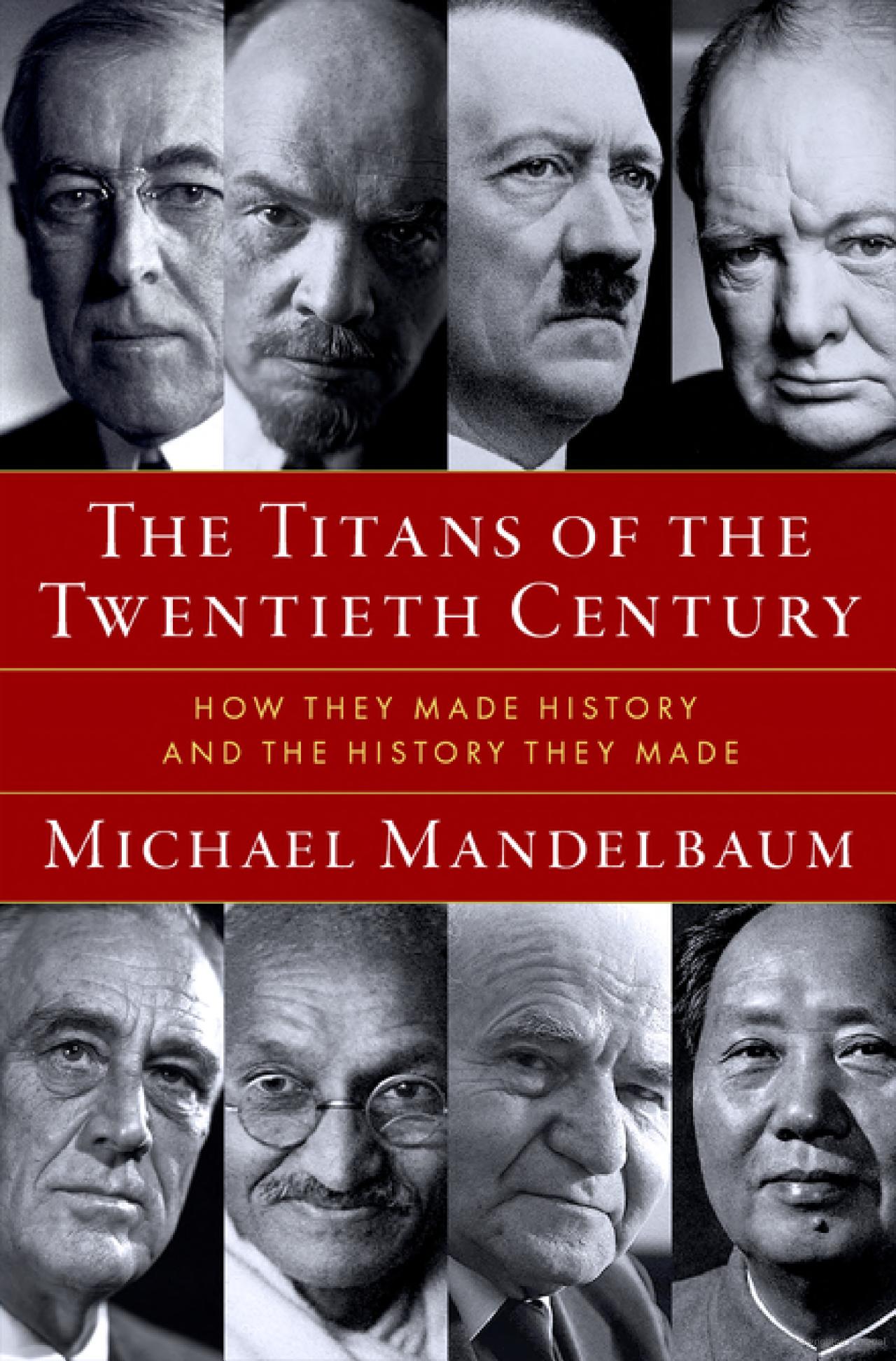

... (read more)The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How they made history and the history they made by Michael Mandelbaum

In his 2015 study of Joseph Stalin, historian Stephen Kotkin suggested that the Bolshevik revolution could have been stopped by just two bullets: one aimed at Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, hiding across the border in Finland but pressing the Bolshevik Party to seize power; a second bullet for Leon Trotsky, on the ground in Petrograd as a determined band of Red Guards, sailors, and soldiers stormed the Winter Palace.

... (read more)On a Tuesday morning in April 1954, Australians awoke to sensational headlines. The wife of Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrov, who had recently sought asylum in Australia, was dragged aboard an aircraft in Sydney, as an impassioned, noisy crowd of a thousand tried to prevent her departure. Whether you were a dock worker or a stockbroker, your morning newspaper carried some version of what has become the Petrov Affair’s most iconic image: Evdokia Petrova, shoeless and eyes streaming, flanked by two bulky Soviet couriers, marching her across the tarmac. By all appearances, a terrified Russian woman was dragged, unwillingly, towards a dire fate in the Soviet Union.

... (read more)Dhoombak Goobgoowana: A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne, Volume 1: Truth edited by Ross L. Jones, James Waghorne, and Marcia Langton

Across more than five hundred pages and written by thirty-three contributors, Dhoombak Goobgoowana contains stories about the University of Melbourne’s relationship with Indigenous Australians.

... (read more)