History

After the prolonged débâcle following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, events in the Middle East in late 2010 and early 2011 seemed to be taking a turn for the better. The ‘Arab street’ had found its voice and democracy, we were led to believe, was on the march. Despite the setbacks that followed 9/11, perhaps Francis Fukuyama’s optimistic liberal triumphalism con ...

Fracture: Life and culture in the West 1918–1938 by Philipp Blom

In 1915 a young Englishman was repatriated from the Western front to Craiglockhart psychiatric hospital in Scotland. Traumatised and disillusioned, he would write ...

... (read more)Australia: :A German traveller in the age of gold by Friedrich Gerstäcker

Formerly only known to historians and specialists, either in the original German or the author's abridged translation, Friedrich Gerstäcker's Australian travelogue (1854), based on ...

... (read more)Britain’s Europe: A thousand years of conflict and cooperation by Brendan Simms

For elections in Britain, the polling stations stay open until late, with counting through to dawn. So it was a sleepless night for many on Thursday, 23 June 2016 ...

... (read more)Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America by Michael A. McDonnell

Michael McDonnell knew he had a bestseller on his hands. Historical biographies regularly top the New York Times bestseller list, and his research uncovered a larger than life figure named Charles de Langlade. Born in 1729 to an Indian mother and a French-Canadian father, Langlade grew up straddling two cultures, but that did not stop him from becoming a le ...

A year or so after I had begun my work in the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions, the immortal words of 'Ern Malley', 'The emotions are not skilled workers', bored a hole into my brain, dug around a bit, and settled there as a perpetual irritant. Malley's phrase has an oblique genealogy. Coined by James McAuley and Harold ...

The Princeton Companion to Atlantic History edited by Joseph C. Miller

Atlantic history and the closely related phrase 'Atlantic World' refer to a geographical/historical way of thinking about interactions among peoples of Europe, Africa, and the Americas between about 1500 and 1900. Practitioners of Atlantic history, like other scholars washed up from the wreck of nation-based historical writing, find it impossible to comprehend the p ...

At the very bottom of Hell, Dante represents Satan with three mouths, each of which endlessly devours a figure personifying treachery and rebellion against God. One of these, predictably enough, is Judas. What may be surprising to the modern reader is that the other two are Brutus and Cassius, the assassins of Julius Caesar. In the medieval vision of the universe an ...

#1 Martin Thomas reads ‘“Because it’s your country”: Bringing Back the Bones to West Arnhem Land'

In 2013 we published Martin Thomas's Calibre Prize-winning essay ‘“Because it’s your country”: Bringing Back the Bones to West Arnhem Land'. This powerful story of the repatriation of Aboriginal bones soon became the best read article on our website and we are delighted to be able to launch the ABR podcast with it.

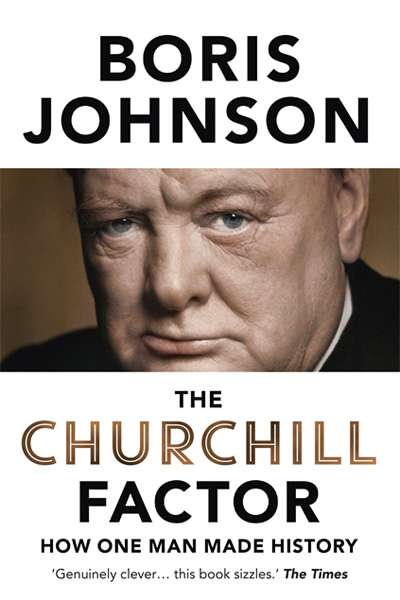

... (read more)The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History by Boris Johnson

Had it not been for the leadership of Winston Churchill in 1940, Nazi Germany would in all probability have won World War II. The most enthusiastic revisionist historian would grudgingly accept this proposition.

As this highly readable account by London Mayor Boris Johnson shows, 1940 was the high point of a career that extended from the 1890s to the 1960s. ...