History

Wizards of Oz: How Oliphant and Florey helped win the war and shape the modern world by Brett Mason

What happens when you mix some of the biggest scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century with the urgency of war? Wizards of Oz, a new book by lawyer and former politician Brett Mason, seeks to provide the answer. It is an account of a friendship between two Adelaide men and their extraordinary scientific achievements during World War II.

... (read more)Partisans: The conservative revolutionaries who remade American politics in the 1990s by Nicole Hemmer

Beginning just as the Cold War finally came to an end, the 1990s were supposed to bring peace, prosperity, and optimism to the United States. Thinking about all that has happened since – the 9/11 attacks, interminable wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the global financial crisis, violent unrest and democratic institutions under threat – it is tempting to look back on the decade as a short-lived golden age. But there has been a growing recognition among scholars and commentators that the roots of America’s contemporary woes can be found in the dark undercurrents of the fin de siècle. Strong economic growth and rapid technological advances had masked growing discontent and rage about inequality, immigration, and globalisation.

... (read more)No publisher or literary agent could have dreamt up or commissioned this remarkable book. It is wholly unexpected and original. It is about some Yolngu clans in north-east Arnhem Land, a group of Vietnam veterans, and an anthropologist named Neville White, who happens to be an old friend of one of Australia’s finest writers, Don Watson. Watson observes Neville, who systematically observes the Yolngu, who are regularly visited by the vets. It sounds like a lugubrious farce and sometimes it reads that way. But it is a deeply serious enquiry into questions at the heart of Australian history, politics, and identity.

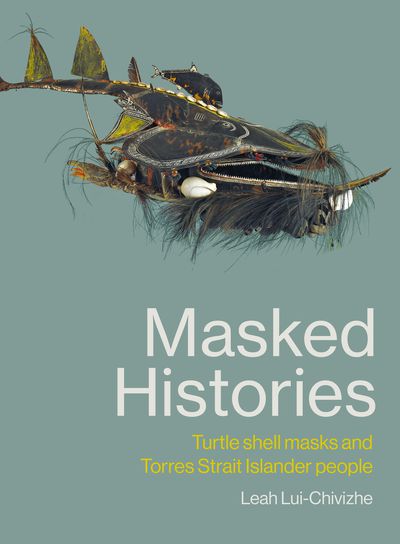

... (read more)Masked Histories: Turtle Shell Masks and Torres Strait Islander People by Leah Lui-Chivizhe

Turtles, Leah Lui-Chivizhe shows us in Masked Histories, are at the centre of Torres Strait Islander lives. They follow the Pacific currents and slipstreams, arriving in the Islands in the mating season of surlal, making available their eggs, their meat, their shells. For millennia, marine turtles have provided Islanders with material for subsistence and ceremony – allowing them to practise ceremony with turtle shell masks so evocative of Islander cultures and histories.

... (read more)Constructing Economic Science: The invention of a discipline 1850–1950 by Keith Tribe

Don’t let the title put you off: this book is not purveying social theory but investigates the historical process by which economics became a university discipline in Britain, focusing on how that event changed the nature of economic knowledge. It thus mixes intellectual and institutional history of the highest quality. ‘Constructing’ in the title refers to the cover image of the model built by Vladimir Tatlin and his colleagues of his planned 400-metre tower. Tatlin was a ‘constructivist’ in the sense of the Russian art movement that needed engineers not philosophers. The tower was never realised, much like the ambitions held for economics by Alfred Marshall, its champion at the University of Cambridge, c.1885–1908, who sits at the centre of this book.

... (read more)Matthew Flinders: The man behind the map by Gillian Dooley

Few names are so ubiquitous in Australian culture or hold such a significant position in its history as that of Matthew Flinders. More than one hundred sites across Australia have been named in his honour, commemorating his accomplishments as a navigator, hydrographer, cartographer, and scientist. Among them are several statues featuring Flinders with Trim, his ever-faithful pet cat and companion, as well as numerous geographic landmarks, electoral districts, and a university.

... (read more)Across the past fifty or more years, indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand have increasingly made political and legal claims about sovereignty and land. As this has occurred, numerous scholars in a broad range of disciplines – especially law and history – have tried to explain how these two matters were dealt with by the British empire in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Often that work has been done in the hope that it will bolster the indigenous peoples’ claims or redeem the settler societies whose legitimacy has been drawn into question because of their unjust treatment of First Peoples.

... (read more)This year, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) celebrates its centenary as the world’s largest and oldest broadcasting institution (the US company NBC was founded four years later, in 1926). Whether it will reach its bicentenary, or even have another ten years of life in anything like its current form is a question facing other British institutions such as the Conservative Party, the monarchy, and indeed the Union of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland itself. Placing the BBC among this group signals its estimable role in defining an imagined community but also the possibility that the existence of these other entities and their function in this process might be finite, subject to challenges from their own internal contradictions as much as from hostile external forces without.

... (read more)Jeremy Bentham and Australia edited by Tim Causer, Margot Finn, and Philip Schofield & Panopticon versus New South Wales and Other Writings on Australia edited by Tim Causer and Philip Schofield

In the centenary of Jeremy Bentham’s death in 1932, there was widespread and somewhat macabre interest in the Australian press in the commemorative dinner at University College London, at which Bentham’s famous auto-icon made an appearance as the guest of honour. Some of the more serious commentary sought to educate readers about this ‘human bridge between the thought of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries’ and more especially about his relationship to Australia. New South Wales was established as an experimental penal colony just as Bentham (1748–1832) was reaching the height of his powers, and could hardly fail to play a dynamic and critical role within his thinking on crime and punishment. Given the origins and nature of the colonies that became Australia’s states, they could not but bear some imprint from the house-philosopher of the Victorian British state, making Bentham, in Judith Brett’s assessment, Australia’s ‘foundational thinker’.

... (read more)The Australians at Geneva: Internationalist diplomacy in the interwar years by James Cotton

In October 2022, the United Nations announced that its Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project (LONTAD) was complete. For the past five years, archivists in Geneva have been preserving, scanning, and cataloguing more than fourteen million pages of historical documents, making them accessible to researchers around the world. Harnessing a technology that people a century ago could hardly imagine, this project has extended the League of Nations’ foundational values of sharing knowledge and cooperating across borders into the twenty-first century.

... (read more)