Biography

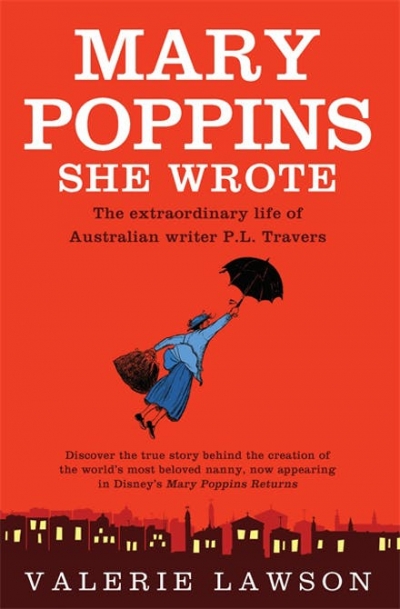

Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The true story of Australian writer P. L. Travers, creator of the quintessentially English nanny by Valerie Lawson

How complex a task it is to write the biography of a writer. For writers, whose daily business is making things up, the truest experience may be one they have imagined. All biographers need to be storytellers and private detectives, but the biographer of a writer must also be a literary critic, must account for how the work relates to the life and escapes the life; beyond this, how the experience of writing it might change how the author apprehends those other parts of experience, called facts.

... (read more)Stanley Melbourne Bruce: Australian internationalist by David Lee

One of the most disconcerting aspects of the 2010 election campaign was the intrusion of former prime ministers and aspirants to that post. Liberals had tired of Malcolm Fraser’s interventions long before he decided not to renew his membership of the party. Labor supporters did not welcome another round of bickering between Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. The interventions of Mark Latham were hardly edifying.

... (read more)My Congenials: Miles Franklin and friends in letters edited by Jill Roe

My Brilliant Career, the book Miles Franklin published in 1901 when she was twenty-one, cast a shadow over her entire life. It sold well and made her famous for a time, but it did not lead to the publication of more works. The glittering literary career foretold by the critics did not eventuate, at least in Franklin’s opinion. ‘The thing that puzzles me,’ she wrote to Mary Fullerton on New Year’s Day, 1929, ‘is how are we to know whether we are a dud or not at the beginning; I mean how long should a poor creature smitten with the egotism that he can write, keep on in face of rebuffs’.

... (read more)Madam Lash: Gretel Pinniger’s scandalous life of sex, art and bondage by Sam Everingham

Madam Lash is a biography of Australia’s most famous dominatrix. Author Sam Everingham provides an engaging insight into the life of the woman who helped bring sadomasochism to mainstream attention in this country.

... (read more)Sharyn Killens is no stranger to the spotlight. After a long career as an entertainer, she is used to appearing in make-up and gown, pouring out a song. She is also a veteran of interviews and media stories, with a different song: that of her own extraordinary life. In The Inconvenient Child, written with her friend Lindsay Lewis, Killens (known on the stage as Sharyn Crystal) relates a wrenching and finally satisfying story of abject misery and triumphant emotion. In the paradigm of classic Australian memoir, her tale needs no bells and whistles to ring true. It is a transfixing performance.

... (read more)The Master: The life and work of Edward H. Sugden edited by Renate Howe

Edward Sugden was the first master of Melbourne University’s Queen’s College, a position he held for forty years. One needs to provide this identification, because although in his day Sugden was regarded as one of Melbourne’s best-known citizens, his is one of those names that has dropped from view. Along with his contemporaries Alexander Leeper of Trinity College and John MacFarland of Ormond, he contributed to what Wilfrid Prest calls ‘the golden age’ of Melbourne University’s colleges.

... (read more)Mr Isherwood Changes Trains: Christopher Isherwood and the Search for the 'Home Self' by Victor Marsh

Living in Berlin during the rise of the Nazis, Christopher Isherwood wrote the stories that first brought him fame and later became the basis for the musical Cabaret. This was the period that Isherwood mined for his ground-breaking memoir, Christopher and His Kind (1976).

... (read more)A Three-Cornered Life: The Historian W.K. Hancock by Jim Davidson

Name a selection of your own most interesting and iconic Australians of the last century. My personal list would begin with John Monash, Donald Bradman, and W.K. Hancock.

... (read more)Biography seems relatively easy to produce, but difficult to write well. It is therefore treated with a certain amount of suspicion by academics. Historians tend to regard it as chatty, not primarily concerned with policy or the identification of social factors; literary people are more sympathetic, but, in order to blot out the prosy or the fact-laden, tend to revert to a default position. Biography for them is basically about writers, and best written by literary academics.

... (read more)The career of one of Australia’s most talented novelists, Barbara Hanrahan (1939–91), was cut short by illness, and her work has now largely slipped from view. I edited several of her novels in the late 1970s for the University of Queensland Press. Whereas other UQP authors of the time, such as the gregarious Olga Masters, enjoyed media attention, with the introspective Barbara Hanrahan it was a struggle to build the readership her talent deserved.

... (read more)